British American Tobacco (BAT) has been out of favour with investors since 2017 when its shares reached a record-high price of more than £56.

Over the next five years, BAT’s shares fell by as much as 50% as investors worried about the long-term future of the cigarette industry in an increasingly restrictive regulatory environment.

With BAT’s shares now close to £33 they have a dividend yield of 6.5% and that is very attractive to most dividend investors.

But British American Tobacco is facing large and obvious headwinds, so the real question is whether that attractive dividend is sustainable.

BAT has a long history of progressive dividend growth

If you’re looking for sustainable dividend growth in the future, it’s usually a good idea to look for sustainable dividend growth in the past. More specifically, I look for a long history of steady dividend growth, supported by growth across revenues, earnings and capital employed.

And as luck would have it, that’s pretty much what BAT has produced since 1998, when its financial services operations were demerged from its tobacco operations (like many other tobacco giants, BAT went on a somewhat bonkers diversification spree from the 1960s to the 1990s, but eventually refocused on tobacco in the late 1990s).

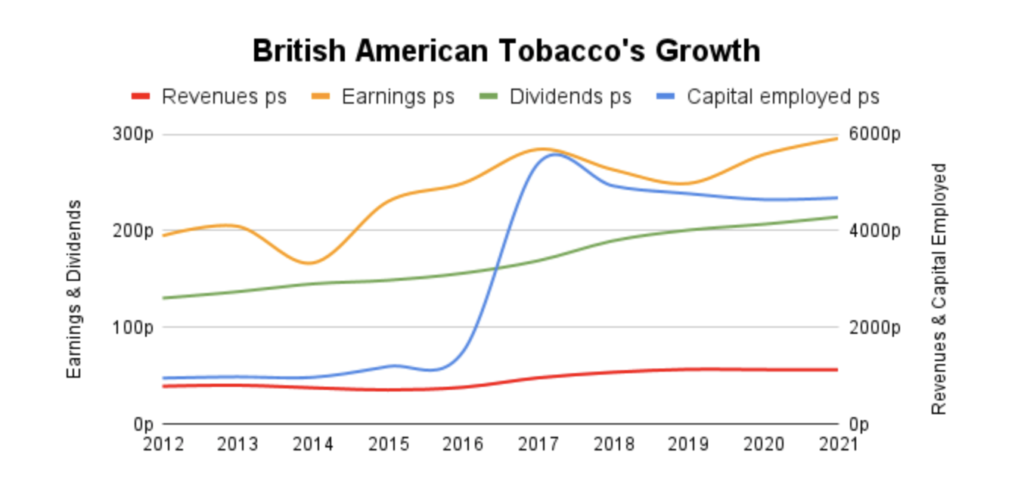

BAT’s growth has generally been steady and comfortably ahead of inflation, with revenues, earnings and dividends increasing by 5-6% per year over the last decade.

The outlier is capital employed, which increased dramatically in 2017. That was caused by BAT’s acquisition of Reynolds American, which increased BAT’s shareholder equity and debts (both key components of capital employed) by more than £50 billion and £30 billion respectively.

This huge acquisition turned BAT into the world’s largest tobacco company, but it’s also a problem because very large acquisitions are often like very large meals; they can give you serious digestion.

In this case, Reynolds American is a tobacco giant and is, therefore, a very similar business to British American Tobacco. That should have made the acquisition easier. Also, BAT already owned more than 40% of Reynolds American and they already had technology-sharing agreements in place, so even before the acquisition, the two companies had a close working relationship.

All of that should have made the integration of Reynolds American much easier and, as far as I can tell, the acquisition didn’t cause any major problems.

That’s good, but the acquisition did have a very negative impact on BAT’s headline profitability.

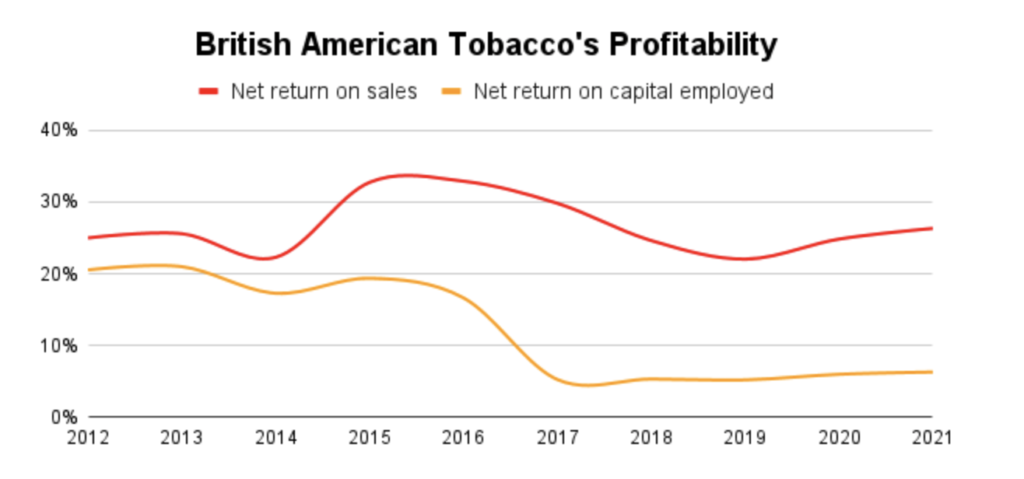

BAT’s headline profitability was good until it acquired Reynolds American

Profitability, measured by return on capital employed, is a key metric because it tells you a lot about:

- How competitive the company is (highly competitive companies tend to produce consistently higher returns on capital)

- How fast the company can grow by organically reinvesting some of its earnings (this tends to be lower risk than borrowing money to fund growth)

In BAT’s case, before 2017 it was consistently producing a net return on capital of around 20%, which is about double the average for UK large-cap stocks. On that basis, BAT looked like a very competitive and highly profitable business.

But after the Reynolds American acquisition in 2017, return on capital collapsed to little more than 5%, which fails to meet my return on capital rule of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in companies that consistently produce net returns on capital above 10%

BAT now fails this test, but I don’t think its recent returns on capital accurately reflect the underlying economics of the business. Instead, I think they’ve been skewed downwards because BAT paid a high price to acquire Reynolds American.

Here’s how that works: Company A has £1m of capital employed and generates a £1m profit every year. That’s a fantastic 100% return on capital. Company B comes along and acquires Company A for £20m. The acquired business still produces £1m profit per year, which is a return of 5% on Company B’s £20m purchase, or a 5% return on capital.

This is basically what happened with BAT. It acquired Reynolds American and the combined business’s earnings went up, but because BAT paid a high price for the business, the headline return on capital collapsed.

However, the business that was producing 20% returns on capital before the acquisition is still there, and once you strip out the accounting distortions caused by the acquisition (mostly intangible assets like acquired goodwill and acquired brand value), the company’s returns on capital are still very good.

But headline return on capital wasn’t the only thing messed up by this acquisition.

BAT’s balance sheet is a mess which is gradually being cleaned up

Taking on £30 billion to buy another company was always going to blow a hole through BAT’s balance sheet. However, management thought that was a price worth paying because the acquisition would turn BAT into the world’s largest international tobacco company.

Being the global leader is nice, but the debt required to fund the acquisition left BAT’s balance sheet in a mess. Here’s my rule of thumb for debt:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if its debts are less than five times its ten-year average earnings

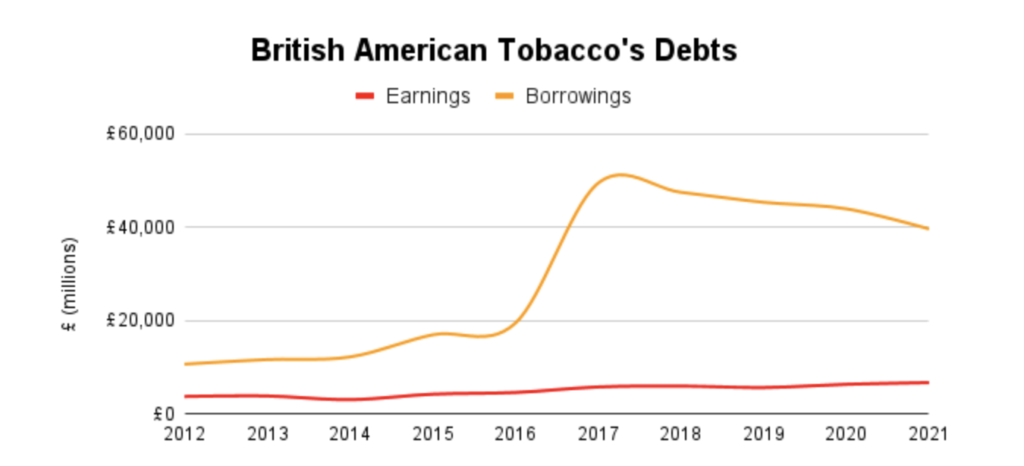

Over the last ten years, BAT earned an average of £5 billion per year, going from £3.8 billion in 2012 to £6.8 billion in 2021.

Immediately after the 2017 acquisition, its debts went from £20 billion to £50 billion. Its debts were already a little on the high side at £20 billion, but at £50 billion they were more than ten times its average profits.

Tobacco is a very steady business because millions of people can be relied upon to smoke cigarettes every day come rain or shine, but even so, I think a debt to average earnings ratio of ten is a serious risk.

Fortunately, the company has focused on reducing debt back towards something more sensible and, as things stand today, its debts are down to a little under £40 billion, giving BAT a debt to average earnings ratio of 8.

I still think that’s far too high, but management seems to be happy with that level of debt. In fact, the company recently announced that cash previously used to reduce debt will now be returned to shareholders through share buybacks.

I like buybacks as much as the next investor, but I’d rather see another year or two of additional debt reduction first.

BAT has a solid financial track record but its high debts are a potential problem

Overall, I think BAT’s track record is very solid if we ignore the price paid for the Reynolds American acquisition. If acquisitions were a core part of BAT’s business model then overpaying would be a serious problem, but it seems that this was a one-off event so the fact that management seems to have overpaid is less of an issue.

What is an issue is BAT’s debts, which are too high.

Normally I wouldn’t touch a company with a debt-earnings ratio of 8 with a bargepole, because an economic downturn could cause the company to cut or suspend its dividend in order to fund debt interest payments.

In BAT’s case, I might make an exception.

First, BAT’s core business is virtually immune to economic downturns as very few people quit smoking just because there’s a recession.

Second, BAT’s debts have reduced from £50 billion in 2017 to £40 billion in 2021 thanks to the tsunami of cash thrown off by the core cigarette business.

Third, BAT’s consistent growth has left its current earnings at almost £7bn, so that £40bn debt pile is only six times its current earnings and that’s fairly close to my “five times” limit.

So if BAT’s earnings continue to grow, and if its debts remain flat or (preferably) decline somewhat, its debt ratio would become more acceptable within a handful of years.

On that basis, I’m not willing to write BAT off as overindebted just yet. That means I don’t think its dividend is obviously unsustainable, at least not until I’ve had a closer look at the business and its market.

Economically, selling cigarettes is a fantastic business

The first thing to note is that BAT sells a product which is, from a cold-hearted capitalistic point of view, very attractive:

- The vast majority of smokers smoke every day, so demand is very consistent

- Like many consumer goods, well-known brands have real power and many people smoke the same brand as their parents and peers

- There is huge brand loyalty, with most smokers sticking to one brand for decades

- The existing competitors are huge, with enormous economies of scale and tens of billions invested in supply chains

- Cigarette advertising is banned in many countries, which leaves more cash available for dividends and makes it harder for smaller or newer competitors to build awareness

- Nicotine is addictive, so smokers tend to keep smoking even if prices go up (they are “price insensitive”)

Together, these factors create an industry where profits are high and consistent, where prices can be increased ahead of inflation and where new competitors are largely non-existent.

In other words, if you ignore the ethics of selling cigarettes, it’s a fantastic business.

But you can’t ignore the ethics because, in the long run, they will be the death of the cigarette industry.

Ethically, selling cigarettes is a questionable business

We have known for many decades that cigarettes can be dangerous and highly addictive, which isn’t a great combination.

As social norms evolve, governments around the world have taken an increasingly hard line against cigarettes and other tobacco products.

Usually, this means higher taxes to make cigarettes less affordable, but it also extends to advertising bans and enforcedplain packaging (which isn’t exactly plain because it usually carries graphic pictures conveying the dangers of smoking).

Given the increasingly negative social and regulatory environment, it should come as no surprise that smoking has been in decline for many years.

For example, total cigarette sales per year (excluding China) have fallen by 25-30% over the last decade as more people quit and fewer people take up smoking.

It’s hard to imagine a future where cigarette sales make a successful recovery. It seems much more likely that sales will continue to decline until at some point governments can make cigarettes illegal without committing political suicide.

This begs two questions:

(1) How has BAT grown while the cigarette industry has declined?

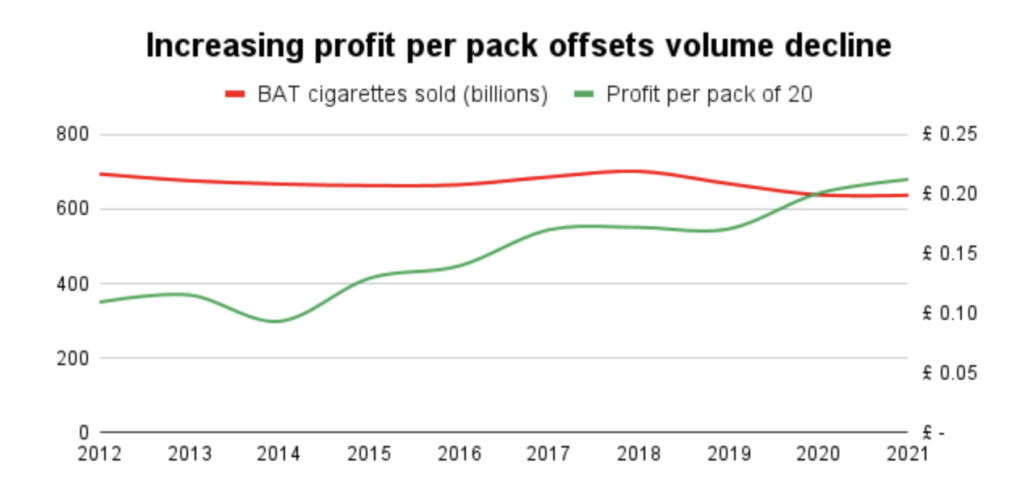

While the industry’s total cigarette sales have declined by 2-3% each year, BAT’s “stick” volumes have been noticeably more robust for most of the last decade; BAT’s volumes have declined by 8% since 2012 compared to 25-30% for the industry as a whole.

So BAT must have consistently taken market share from its peers to offset most of the overall market’s decline.

In addition, BAT has been extremely successful at increasing its profit per pack, by increasing prices and shifting consumers from less profitable “value” brands to more profitable “premium” brands.

Over the last decade, those profit-increasing efforts have more or less doubled BAT’s profit per pack from about 10p to 20p. That, combined with market share gains, has helped BAT produce consistent earnings growth at around 6% per year despite the market’s overall decline.

(2) Can BAT avoid the cigarette industry’s bleak future?

If cigarette sales eventually go to zero then it doesn’t matter how much profit BAT makes per pack, so for BAT to prosper long-term, it must have a future beyond cigarettes and, perhaps, beyond nicotine.

This isn’t exactly a dazzling insight and the tobacco industry has been aware of this for decades.

In BAT’s case, it first mentioned its R&D efforts in “next generation products” (NGP) in 2012. Since then, progress toward a post-cigarette future has continued at pace:

- 2013: BAT launches its first vaping product.

- 2015: BAT launches its first tobacco heating product and signs a vapour technology sharing agreement with Reynolds American.

- 2016: BAT’s vaping business becomes the largest in the world outside the US and BAT announces the acquisition of Reynolds American and its US vaping business.

- 2017: BAT goes into full-on “transformation” mode, aiming to transform into a fast moving consumer goods business focused on soothing and stimulating consumers. BAT sets itself the ambition of world leadership in next generation products, with NGP revenues targeted to grow from £0.5bn in 2017 to £5bn in 2025.

BAT has taken a multi-category approach to moving beyond cigarettes, with three main categories covered with three global brands: vaping (Vuse), tobacco heating (glo) and modern oral (Velo).

Vuse has grown to become the world’s #1 vapour brand, glo is #2 or #3 in most of its markets and Velo is #1 in all of its markets outside the US.

Revenue from these brands has grown from £0.5bn in 2017 to £2bn in 2021 and remains on track for BAT’s target of £5bn in 2025.

2021 also marked the first year in which losses from these currently sub-scale businesses began to shrink. This is good news because the cost of scaling up these businesses has been a drag on BAT’s earnings in recent years, and as those losses turn into profits over the next few years that headwind should turn into a tailwind.

For a cigarette business, moving into vaping or tobacco heating products is the obvious thing to do, but these products still rely on nicotine which could itself be regulated out of existence at some point.

To avoid that existential threat, BAT has spent years investigating and investing in “beyond nicotine” products through Btomorrow ventures. This venture capital business has invested in start-ups and scale-ups such as Awake Chocolate and Blockhead, and I think BAT has three major strengths which should help it compete effectively outside its traditional tobacco and nicotine-based markets:

- Long-established R&D capabilities specialising in plants and ingested chemicals

- Decades of global brand-building experience

- A well-oiled global distribution machine

Of course, moving into products that stimulate or soothe consumers will mean stepping on the toes of some very large and established competitors. But BAT isn’t exactly a seven stone weakling.

After all, BAT’s earnings are similar to Unilever’s, and while Unilever is one of the world’s largest advertisers, cigarette advertising bans leave BAT with a significantly larger amount of cash to invest in developing and growing new brands (here’s are my thoughts on Unilever).

So although it’s early days for these beyond-tobacco and beyond-nicotine products, I certainly think BAT has the capabilities and motivation to generate significant profits from these businesses.

And on that basis, I think it’s reasonable to assume that BAT can survive beyond the end of the cigarette industry, but can it grow its post-cigarette profits quickly enough to sustain or even grow its dividend?

Estimating British American Tobacco’s future dividends

BAT paid a 2021 dividend of £2.16, giving it a dividend yield of 6.5% at its current share price of £33.

As for 2022, it’s already announced a £2.18 dividend and a £2 billion share buyback.

Both dividends and buybacks are cash returns to shareholders, so BAT’s intended cash return to shareholders for 2022 comes to almost £7 billion, which is about £3 per share.

That gives BAT a very attractive “shareholder yield” from dividends and buybacks of 9%. A 9% shareholder yield is of course very nice, but is it sustainable?

Over the next five years, it could be. Management currently expects BAT to produce around £40 billion of free cash flows over the next five years, which is an average of £8 billion per year. On that basis, the current £7 billion cash return to shareholders should be sustainable over the medium term.

But what about the longer-term? Is an almost £3 per share dividend plus buyback sustainable to 2030?

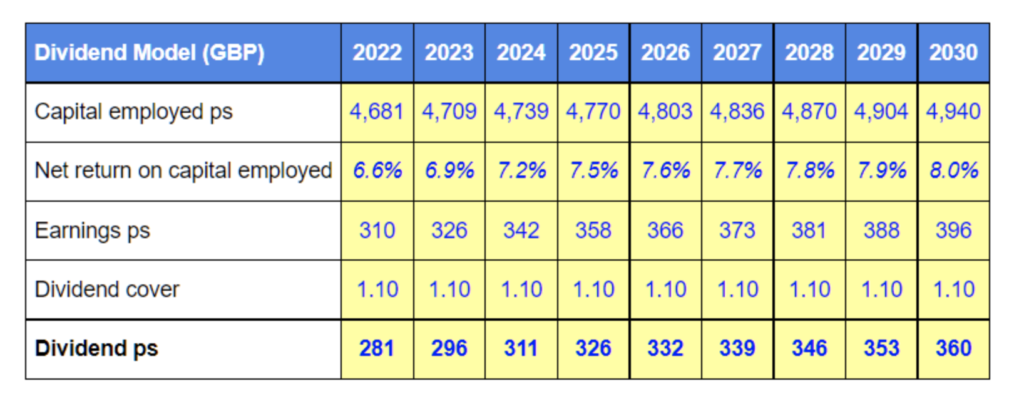

To answer that, let’s imagine a scenario where BAT not only maintains that £3 payout but actually grows it by 3% every year for the next decade.

Here’s the scenario:

- NGP profits improve by £250m/yr, from reported losses of £1bn in 2021 to management’s target of break-even in 2025

- NGP profits continue growing by £250m/yr until they reach £1.25bn in 2030

- The combustibles business produces sufficient earnings to grow BAT’s overall earnings by 3% per year to 2030

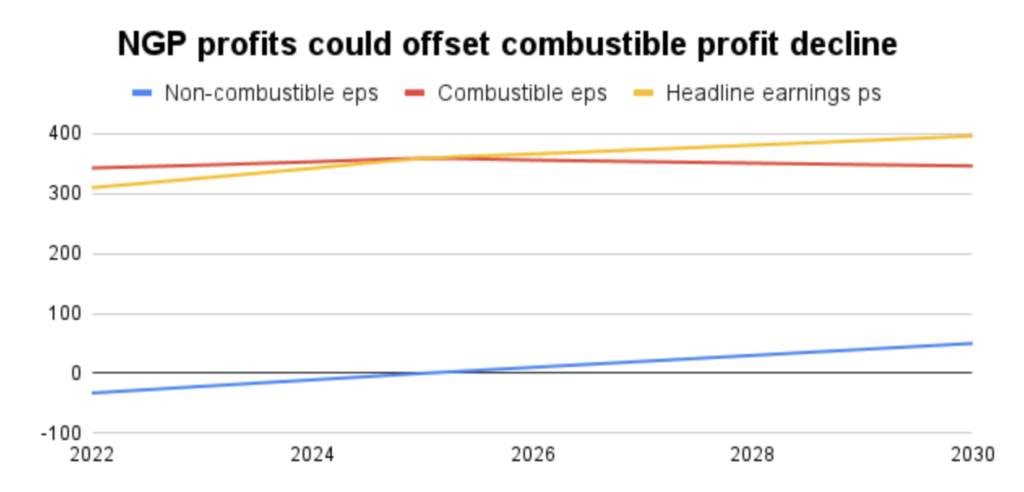

Here’s a chart showing what that would look like:

The blue line shows NGP losses gradually turning into profits and the amber line shows headline earnings growing at about 3% per year.

To achieve that 3% earnings growth rate, combustible earnings would need to increase by about 1.5% per year to 2025. Given BAT’s history of inflation-beating combustibles growth, I don’t think that’s an unrealistic assumption.

After 2025, a 3% headline earnings growth rate can be sustained even if profits from the combustibles business go into slow decline. In the chart, that shows up as a declining red line after 2025.

So according to this scenario, BAT could grow its overall earnings by 3% per year to 2030 as long as (a) its NGP profits grow in line with expectations and (b) its combustibles business grows slowly to 2025 and then goes into slow decline.

Growth doesn’t appear out of thin air, so BAT needs to be able to retain enough of its earnings to fund this growth, and I think it can.

In the above scenario, BAT’s 2022 earnings would cover a near-£3 “dividend” (dividend plus buybacks) 1.1-times over. That’s a thinly-covered dividend, but if we assume that BAT’s return on capital continues to improve back towards historical norms, BAT would have sufficient retained earnings to drive earnings and dividend growth at the scenario’s 3% growth rate.

That would take BAT’s dividend (including buybacks) from almost £3 in 2022 to more than £3.60 in 2030, which would be an 11% yield on today’s share price of £33.

Of course, reality will be different from this scenario, but that isn’t the point. The point is to see whether BAT could, using a reasonable and conservative set of assumptions, grow its dividend ahead of the historical rate of inflation over the next decade. And I think it could.

So I think it’s reasonable to assume that BAT’s dividend is sustainable until at least 2030.

As for the very long-term, I think cigarette sales are likely to continue declining and the post-cigarette products remain very early-stage and unproven. So I think it’s realistic and conservative to assume that BAT’s revenues, earnings and dividends stall after 2030 and remain flat in nominal terms.

In other words, after adjusting for inflation, my assumption is that BAT and its dividend will slowly decline after 2030 (in reality, shrinking companies tend to hold their dividends flat for too long and then cut them abruptly).

Does that make BAT a no-go for long-term dividend investors? Not necessarily.

With a 9% yield from dividends and buybacks, BAT could still be an attractive investment for income-seeking investors, so I think it’s worth estimating a fair value for this business.

Estimating BAT’s fair value

Economically, a company only has value if it returns cash to shareholders at some point in the future, so if we want to estimate the present or fair value of a company, we need to estimate its future dividends.

As luck would have it, we just estimated BAT’s future dividends, so I can just plug those dividends into a discounted dividend model (like the one in my investment spreadsheet) and it will tell us the present value of those dividends.

My dividend model uses two discount rates (which is effectively the desired rate of return).

The first discount rate is 7% per year because 7% is the UK stock market’s long-run average return. This gives us a “fair value” estimate for BAT:

- Fair Value: Based on the scenario above, at £47.85, BAT’s shares would produce a long-term annualised total return of 7% per year

The second discount rate is 10% because that’s my personal target rate of return. This gives us a “good value” estimate:

- Good Value: Based on the scenario above, at £33.03, BAT’s shares would produce a long-term annualised total return of 10%

That’s very interesting because BAT’s current share price of £33 matches up almost exactly with that “good value” estimate.

So if the above scenario does turn out to be conservative, and if you bought BAT at £33, it would produce a long-term annualised return of more than 10%.

On that basis, I would be happy to invest in BAT at today’s price.

The only remaining question is: How much to invest?

Calculating a target position size for BAT

A stock’s position size should reflect, at least approximately, its expected risk and return profile.

In other words:

- Holdings with lower expected risks and higher expected returns should have larger position sizes

- Holdings with higher expected risks and lower expected returns should have smaller position sizes

There are a million ways to do this, but I start by categorising holdings as defensive or cyclical and give them a default size of 4% or 3% respectively (I’m looking to hold around 20-25 companies, so 3-4% each is in the right ballpark).

Those defaults are then adjusted up or down based on each holding’s valuation. The more attractive the valuation (lower price relative to fair value), the larger the target position size and, of course, the opposite applies.

In BAT’s case, I classify it as cyclical because it’s a defensive stock going through a major transformation. So it gets a default target size of 3%.

BAT’s current share price of £33 is well below my estimate of fair value and matches my estimate of good value, and that increases its target size. I do this formulaically using my investment spreadsheet, and in BAT’s case, its target size increases to 4.5%.

So as things stand today, I’d be willing to hold BAT with a position size of around 4.5% and, in fact, I do hold BAT with more or less that position size in both the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio and my real-world portfolio.

Originally published by ukdividendstocks.com and reprinted here with permission.