GlaxoSmithKline (now known simply as GSK) has long been a favourite with dividend investors.

Despite that popularity, the sad reality is that GSK has long been a disappointment on almost every front, with its share price stuck in a sideways range for more than 20 years and its dividend remaining flat for the last eight years.

Unsurprisingly, shareholders have been pushing for radical change to break this cycle of stagnation and, in 2022, radical change is what they got.

GSK’s consumer healthcare business (perhaps the most attractive part of the company to dividend investors) has been spun off and the remaining business (sometimes referred to as New GSK) will now focus exclusively on vaccines and prescription medicines.

These are significant changes, so I thought this would be a good time to review this New GSK from a dividend investor’s perspective.

Table of contents

- A research-based pharmaceutical giant creating new vaccines and medicines

- Born from the merger of four leading healthcare companies

- GSK’s performance since 2009 has been underwhelming

- General medicines have been a serious drag on performance for years

- GSK’s strategy is focused on specialty medicines and vaccines

- Estimating GSK’s future revenues, earnings and dividends

- Estimating GSK’s fair value using a discounted dividend model

- Would I invest in GSK at the right price?

A research-based pharmaceutical giant creating new vaccines and medicines

I’ll begin with a review of GSK’s business model.

GSK is a research-based pharmaceutical company (also known as an innovator or originator drug company), which means it invents new drugs, brings them to market and sells them all over the world.

Each new drug has a lifecycle which involves a number of recurring steps:

Step 1: The drug development process begins with GSK spending years and sometimes decades researching and developing a potential new drug that it hopes will provide materially better patient outcomes than existing drugs.

Step 2: If the drug is sufficiently promising in terms of effectiveness, safety and cost, GSK will try to obtain patents to give it the exclusive right to sell the drug for up to 20 years.

Step 3: Once patents are granted, the drug will be put through a series of clinical trials. In the first phase, the drug will be tested on a small number of people. If it proves sufficiently safe and effective, it will move onto the next phase where it will be tested on a larger number of people. If the drug proves to be effective and safe after three or more successively larger phases, the drug may be granted a licence by the regulator.

Step 4: Unlike most products, the price of patented drugs is often regulated, as is the case in the UK. In the UK, the price will be based on the increase in “quality-adjusted life years” provided by the new drug relative to existing drugs. GSK uses these calculations to make decisions about which areas of medical research it should fund, so that it doesn’t spend years researching a new drug that payers (governments, national health services, hospitals, doctors or patients) will be unwilling to buy.

Step 5: Having entered the market, the new drug will be sold exclusively by GSK for up to 20 years after the patents were granted. With limited competition, GSK will try to make enough profit from the drug to pay dividends to shareholders while also funding research into the next generation of vaccines and medicines.

Step 6: When the drug’s patents expire, it becomes a generic drug that any sufficiently capable generic manufacturer can produce. Generic drugs are pure commodities (paracetamol is paracetamol, whichever company makes it), so generic manufacturers are low-cost operators where low prices are all-important. GSK can’t compete with cheap generic drugs because it spends billions on ground-breaking research, so when a drug’s patents run out, GSK’s profits from that drug will usually collapse in a relatively short period of time.

Step 7: When GSK can no longer generate acceptable returns from the drug, it might licence the brand name to generic manufacturers, sell the brand name or simply stop production, at which point the drug’s lifecycle is effectively over as far as GSK is concerned.

Inventing ever-better vaccines and medicines is difficult and expensive, so GSK focuses its R&D efforts on a relatively small number of therapeutic areas where it may have competitive advantages. These are:

- Infectious diseases (including covid-19, meningitis, shingles, flu, polio)

- HIV (through GSK’s subsidiary, ViiV Healthcare)

- Oncology (mostly blood cancers, gynaecological cancers and solid tumours)

- Immunology (including asthma, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis)

Another way to segment healthcare is to think of it in terms of prevention and treatment, which translates into vaccines and medicines and that’s how GSK organises its three division.

Vaccines Division (30% of GSK’s revenue)

Vaccines help prevent infectious disease by boosting the patient’s immune response. GSK has the broadest portfolio of vaccines in the industry and about 70% of its vaccine sales relate to diseases most people are familiar with: shingles, diphtheria, tetanus, polio, meningitis and influenza.

In total, more than 2 million GSK vaccines are injected every day and four in ten people receive a GSK jab of one sort or another during childhood.

In terms of effectiveness, more than 90% of GSK’s portfolio has a vaccine efficacy of more than 90%, providing high levels of protection for patients. This also provides high levels of protection from competitors using newer technologies, such as mRNA vaccines, because those vaccines would offer little additional benefit to offset their higher costs.

GSK also has the largest pipeline of potential new vaccines in the industry, with 16 candidates currently undergoing clinical trials, five of which are expected to launch by 2026.

Of course, covid-19 vaccines have generated a lot of attention over the last year or so, but GSK saw relatively little gain from the pandemic. In 2020, the pandemic was actually a headwind for GSK as lockdowns and other restrictions led to fewer non-covid vaccinations and prescriptions. In 2021, GSK’s pandemic-related sales came to £1.4 billion (about 6% of revenues) and in 2022, covid-related sales are expected to be not much more than £500 million.

Despite largely missing out on covid vaccine profits, GSK has launched other important vaccines in recent years, including Mosquirix, the world’s first malaria vaccine (malaria kills about 600,000 people every year).

Speciality Medicines Division (33% of revenue)

Specialty medicines are prescribed by specialists in hospitals rather than generalists such as GPs. They are either high-complexity, high-cost or high-touch (they’re often injectables rather than tablets) and they’re often used to treat complex, rare or life-threatening conditions such as cancer and HIV. Their cost and complexity make it harder for generic manufacturers to copy them after their patents run out, and this is good for GSK because it extends the period where GSK has little or no competition.

More than half of this division’s revenues come from ViiV Healthcare, one of the world’s leading HIV-focused pharmaceutical companies. HIV treatment and prevention is a significant market, with more than 38 million people living with HIV and around 1.7 million new infections each year.

General Medicines Division (37% of revenue)

General medicines are sometimes known as “white pills”, because that’s what most of them are, and they’re usually prescribed by non-specialists such as GPs. They’re less complex and easier to make than specialty medicines, so it’s much easier for generic manufacturers to copy them and general medicines are the bread and butter of most generic drug companies.

Born from the merger of four leading healthcare companies

GSK was previously known as GlaxoSmithKline and it was born in 2000 from the merger of Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham. As those double-barrelled names suggest, Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham were also created through mergers and acquisitions.

In Glaxo Wellcome’s case, Glaxo acquired Wellcome in 1995. Both companies had long histories as research-driven pharmaceutical companies, but Glaxo had painted itself into a corner. More than 40% of its revenues were coming from a single product, Zantac, leaving Glaxo massively exposed to the loss of Zantac’s patents. To offset that risk, Glaxo acquired Wellcome to diversify away from Zantac, to broaden its portfolio more generally and to gain additional economies of scale.

SmithKline Beecham was created by the merger of SmithKline Beckham and Beecham Group. SmithKline was an almost 200-year-old pharmaceutical business and Beecham was a more than 200-year-old company, famous for selling Beecham’s Pills. This merger was mostly about creating an industry giant with a huge R&D budget and access to markets globally, but it was also about SmithKline’s need to diversify away from Tagamet, its blockbuster drug that had recently seen its patents expire.

Perhaps the most important point here is that GSK exists largely because the patents on two blockbuster drugs were expiring with nothing to replace them. This is known as the patent cliff and it is a recurring theme in GSK’s history.

GSK’s performance since 2009 has been underwhelming

In the years immediately following the merger, GSK performed well.

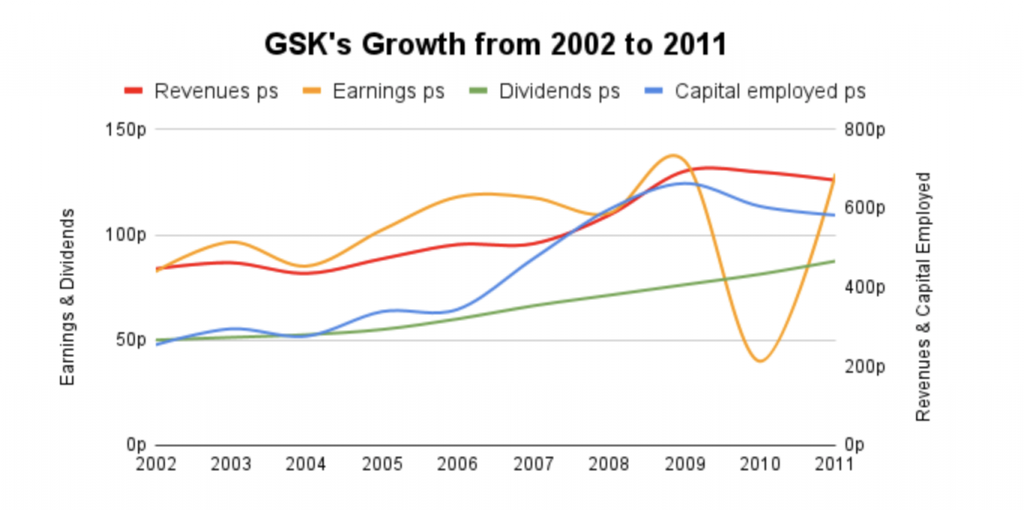

The chart above shows what I think are a company’s main inputs and outputs.

The main inputs are:

- Capital employed (you can think of this as property, research equipment, manufacturing facilities, inventory and other assets) and

- Revenues (money flowing into the company from customers)

The main outputs are:

- Earnings (what’s left over from revenues after expenses are deducted) and

- Dividends (what’s paid out to shareholders after some of the earnings are retained to fund growth)

From 2002-2011, GSK’s capital, revenues, earnings and dividends were all growing at a broadly consistent high-single-digit pace.

However, after 2009, as the right-hand side of the above chart begins to show, things started to go sideways and that has continued until today.

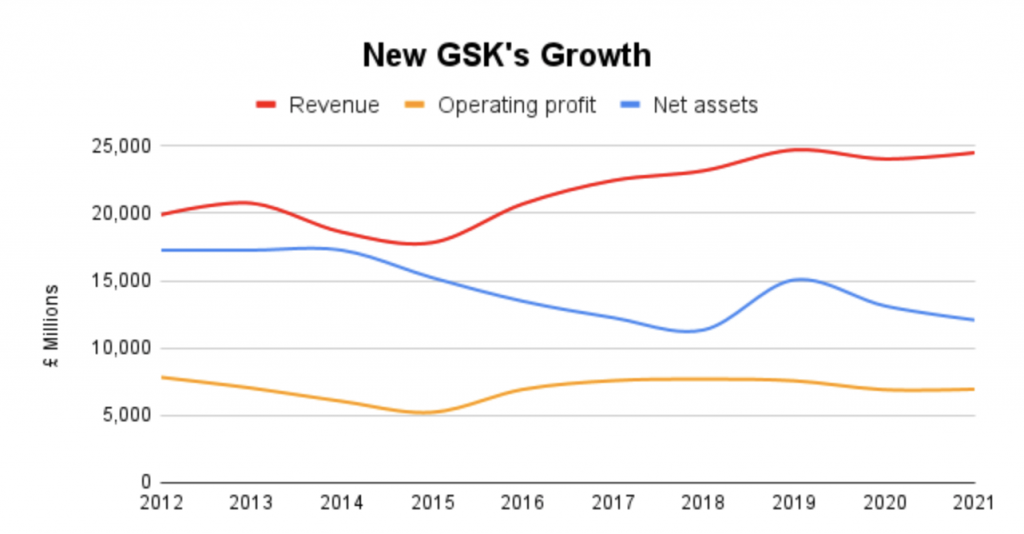

GSK’s headline performance over the last decade has been disappointing, but to see what’s really going on, we need to strip out the results of its recently demerged consumer healthcare division, leaving just the results of New GSK.

Unfortunately, GSK didn’t report capital employed or earnings on a per division basis, but it did report net assets and operating profit, so we can use those instead.

When we strip out the consumer healthcare division, New GSK’s results over the last ten years are just as flat as they were before. Yes, revenues have gone up, slowly, but operating profits have been flat and net assets have gradually declined.

In the words of Mervyn King, what is going on here? Why did a previously successful group of four companies turn into a no-growth sluggard?

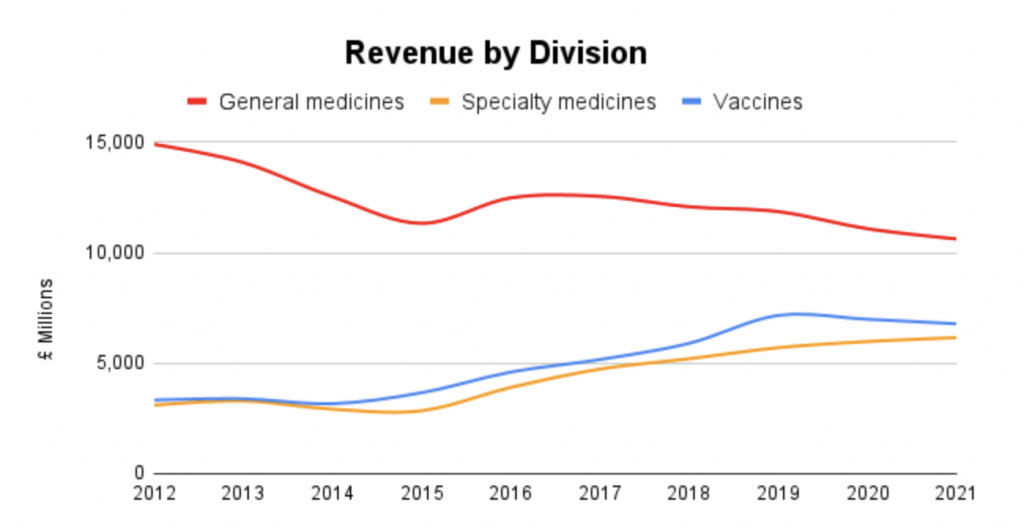

If we separate out the results of GSK’s general medicines, specialty medicines and vaccines divisions, the answer becomes clear.

General medicines have been a serious drag on performance for years

Sales from general medicines have been in decline for years and the percentage of revenues generated by general medicines has fallen from 70% a decade ago to just 37% in the first half of 2022.

This decline has been enough to more or less offset the positive progress made in specialty medicines and vaccines.

Once again, the question is: What is going on here? Why have general medicines performed so badly?

To understand what is going on here, we can look at a developed healthcare market like the UK and use it as a proxy for developed markets more generally.

Weak regulation and a fragmented market favoured branded drugs

Looking back to the first half of the 20th century, the UK had no national health service and little or no regulation of vaccines and medicines.

With no national health service, medicines were mostly sold to patients by chemists, doctors and a limited number of private and volunteer hospitals. These buyers were in many cases as ignorant of medical science as their patients, and they often sold whatever their patients would buy.

And what patients would buy, given that there was little or no regulation of medicines, was brand-name drugs from well-known, trusted companies like Glaxo and Wellcome. What they didn’t want was unbranded drugs from unknown companies.

This environment made it easy for established, well-known companies to dominate the market. In addition, they could sell their branded products at relatively high prices compared to less well-known alternatives, just as Burberry and Unilever do.

However, in the second-half of the 20th century all of that began to change, thanks to increasingly tough regulations and the rise of national health services like the NHS.

Tough regulations and national health services gave the advantage to generic drugs

On the regulatory front, the Thalidomide scandal of the late 1950s and early 1960s was a watershed moment. The UK began regulating drugs more seriously and, over time, those regulations became more and more robust.

Eventually, it became possible for generic manufacturers to prove that their unbranded generic drugs were chemically equivalent to the branded drugs manufactured by innovators like Glaxo and Wellcome.

At the same time, the NHS appeared and began to focus on controlling the cost of drugs. It did this by centralising drug procurement, using its massive bargaining power to bring down prices through negotiation or regulation. It also began educating doctors about the benefits of generics, eventually turning the prescription of generics into best practice. Over a period of several decades, this drove a cultural shift where doctors became comfortable prescribing generic drugs and patients became comfortable taking them.

These changes led to a massive decrease in the prescription of branded general medicines in the UK, falling from 90% of all general medicines in 1976 to less than 20% today, and a similar trend can be seen in other developed healthcare markets.

This shift from branded general medicines to much cheaper generics has been a serious headwind for GSK’s general medicines division, but that isn’t its main problem.

Justifying the higher price of new general medicines is becoming near-impossible

The main problem is that the NHS now puts all new drugs through a detailed cost/benefit analysis to see if they are sufficiently better than existing drugs.

As an overly simplistic example, if a new drug is 10% better than existing generics but costs 50% more, the NHS won’t buy the new drug, despite the fact that it is better than existing drugs.

Putting new drugs through a detailed cost/benefit analysis has significant implications. After all, if the NHS and other national health services won’t buy a new drug because its additional benefits don’t outweigh the additional costs, the market for the new drug will shrink dramatically. If it shrinks too far, it might not be worth developing the drug in the first place.

This is exactly what has happened to general medicines. Existing generics are so effective and cheap that new general medicines are finding it increasingly difficult to meet the cost/benefit demands of governments, regulators and national health services.

This has created a perfect storm for companies like GSK that primarily sold branded general medicines. GSK found itself in a position where sales of its legacy general medicines were declining faster than ever, because doctors were being pushed to prescribe generics instead. At the same time, it couldn’t come up with new general medicines that were sufficiently better than existing generics, so it wasn’t able to offset the loss of sales as legacy drugs went off-patent.

A good example is the decline of Advair, GSK’s biggest seller for many years, with peak revenues of around £5 billion at the beginning of the 2010s. That was about 25% of New GSK’s revenues and the loss of Advair’s patents and the lack of a replacement has been a major part of GSK’s problems over the last decade.

Unsurprisingly then, GSK’s strategy for most of the last decade has been focused on offsetting the decline of general medicines by shifting the company towards the far more attractive markets of vaccines and specialty medicines.

GSK’s strategy is focused on specialty medicines and vaccines

As I mentioned earlier, revenue from general medicines has declined from 70% of New GSK’s revenues a decade ago to 37% today. Since specialty medicines and vaccines make up the rest, their contribution has grown from 30% a decade ago to 63% today. More importantly, they’ve grown in absolute as well as relative terms, taking their combined revenue from £6.4 billion in 2012 to £12.9 billion in 2021. That’s an annualised growth rate of about 10% per year, which is not to be sniffed at.

There are several reasons why vaccines and specialty medicines have grown over the last decade, and why they’re likely to continue growing in the future:

(1) New specialty medicines and vaccines can offer significant benefits to patients relative to their additional cost. Because of this, the NHS and other buyers are happy to pay for them and in recent years, almost all of the industry’s big blockbusters have been specialty medicines or vaccines.

(2) Specialty medicines and vaccines are expected to continue outpacing general medicines in terms of additional bang for the buck, so their markets are expected to continue growing.

More specifically, some forecasters expect global sales of specialty medicines to grow at near-double-digit rates over the medium-term, reaching 60% of total expenditure in high-income markets by the middle of this decade. As for vaccines, the global vaccine market is expected by some to grow by as much as 15% per year over the next few years.

(3) Specialty medicines and vaccines are much harder for generic manufacturers to copy. These aren’t simple medicines where you stick a white chemical powder into a capsule; they’re often biological in nature, often injectable and often require more complex and expensive regulatory hurdles to jump before they can be sold to the public. Relatively few generic manufacturers have these capabilities, and for those that do, it still takes a lot longer to develop and bring to market a generic specialty medicine compared to a generic general medicine.

Also, doctors are still used to prescribing branded specialist drugs rather than generics, so there is a cultural barrier to specialty generics that is yet to be fully broken down.

All of that is even more true of vaccines. Vaccines are even more technically demanding to develop and manufacture, and the cultural barriers to generic vaccines are even greater (covid showed that there are still significant cultural barriers to branded vaccines, let alone generic vaccines). In addition, many vaccines need to be reformulated annually to keep up with ever-changing viruses. This requires lots of research and development and that favours innovators like GSK rather than generic manufacturers.

(4) Specialty medicines and vaccines are becoming more closely related in terms of the underlying science and technology, so R&D investment in specialty medicines can benefit vaccines and vice versa. This wasn’t the case with general medicines, where R&D investment had little benefit to the rest of the company.

Given general medicines’ ongoing decline and the lack of synergies with the rest of the business, management has launched a new strategy to explicitly re-position GSK as an almost pure-play specialty medicines and vaccines business. The strategy has the following main steps:

(1) Sell the consumer healthcare business

(2) Optimise the general medicines division for cash extraction

(3) Cut the dividend to free up more cash

(4) Reinvest the cash generated by steps (1) to (3) into specialty medicine and vaccine R&D to drive growth

I think that’s the right strategy and I think it has a good chance of returning GSK to growth over the next decade.

Estimating GSK’s future revenues, earnings and dividends

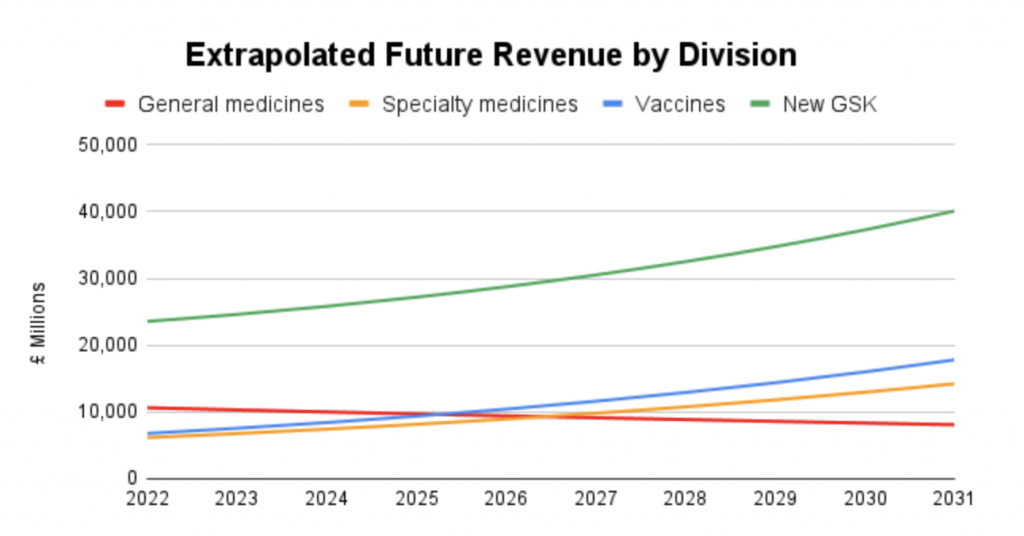

One way to get a very ballpark idea of what GSK’s future might look like is to simply extrapolate past trends. In this case, we can extrapolate the 3% annual decline of GSK’s general medicines division and the respective 10% and 11% growth rates of its specialty medicines and vaccines divisions.

In this simple extrapolated scenario, specialty medicines and vaccines both overtake general medicines in terms of revenue somewhere around the middle of this decade. More importantly, the growing parts of the business are larger than the shrinking parts (unlike a decade ago, when the shrinking general medicines division dominated), so overall revenues grow by about 5% per year during the early 2020s and by about 7% in the late 2020s.

This would take GSK’s overall revenues from £24 billion in 2021 to £40 billion in 2031.

Is that scenario remotely realistic? It might be, because the underlying markets are growing quickly enough to support that level of growth, and with its reduced dividend, GSK would have enough cash to fund the necessary investment in R&D and physical assets.

However, while that projection may be achievable, I wouldn’t call it conservative.

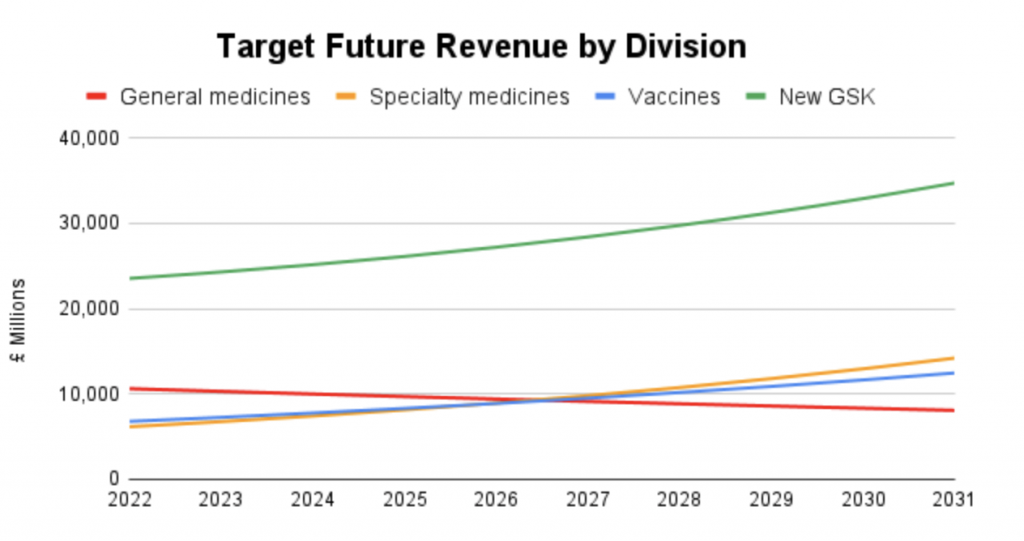

A more conservative projection can be found in GSK’s recent 2021 investor day event, where management laid out some very credible plans to grow GSK’s revenues from £24 billion in 2021 to at least £33 billion by 2031. This is expected to be driven by a slight decline in general medicines, double-digit growth in specialty medicines and high-single-digit growth in vaccines, with all of these targets excluding pandemic-related sales.

Plugging those targets into an updated version of my investment spreadsheet gives the following revenue targets per division.

This is almost identical to the simple extrapolation scenario above, with just a little more conservatism added in. This produces an overall revenue growth rate for the period of about 3.5% per year, which I think is both realistic and conservative.

To estimate future earnings, we can also lean on management’s target, which is to get operating margins back above 30% by 2026. That would take operating profit from about £7 billion in 2021 to about £10 billion in 2031. If we assume that about 30% of operating profits are spent on tax and debt interest, that gives us enough information to estimate future earnings per share.

Management have also said they’re targeting a dividend payout ratio of between 40% and 60%, or 50% on average across the investment cycle, which is equivalent to a dividend cover of 2-times.

With all of that information to hand, we can now build a model for GSK’s future revenues, earnings and dividends.

In summary, and as per management’s targets, revenues go from about £25 billion in 2022 to £33 billion by 2031, operating margins increase to 30% by 2026 and dividend cover stays at 2-times.

This gives us a scenario where GSK’s dividends grow from 61p in 2022 to 86p in 2030.

With GSK’s share price currently at £13.80, a 61p dividend would put GSK’s dividend yield at 4.4% with, coincidentally, a medium-term dividend growth rate also of 4.4% per year.

In reality, management has already set a target dividend of 56p in 2023, which is quite a bit below the 64p dividend in the above model. I could adjust the model to take account of that, but my assumption is that if the 54p dividend turns out to be too low (i.e. GSK is retaining more of its earnings than it can sensibly invest in R&D or productive assets) the excess cash will just be paid out as special dividends or as higher dividends later in the cycle. Either way, it wouldn’t make a huge difference to the model.

Looking beyond 2030, I have estimated GSK’s long-term dividend growth rate at 3.5% per year. This is above expected long-term growth rate of the global economy (which is generally expected to grow at something close to 3%) because healthcare spending is expected to increase as a percentage of global GDP as the world’s population ages through the rest of the 21st century.

However, given the level of uncertainty which is part and parcel of GSK’s business model (primarily its dependence on short-term patents), my estimate for GSK’s long-term growth rate is only slightly above the expected growth rate of the global economy, which I think is a conservative assumption.

So, we now have what I think is a realistic and conservative estimate for GSK’s future dividends. Our next task is to value the company using a discounted dividend model.

Estimating GSK’s fair value using a discounted dividend model

I won’t delve into the details of how discounted dividend models work or why they are the theoretically correct way to value stocks. This article on my old website has a detailed description and Warren Buffett does a much better job of explaining it than I could in the video below.

If you don’t want to watch the video below then a short description is that the fair value of a company (also known as its intrinsic value) is equal to the sum of all its future dividends and other cash returns to shareholders, discounted (reduced) by a fair rate of return.

Personally, I like to calculate both a fair value price and a good value price for a company. Fair value is effectively the price I would sell at and good value is the price I would buy at (it’s a bit more complicated than that, but that’s the general idea).

To calculate fair value, I use the UK stock market’s average annual return of 7% as the discount rate. For good value, I use 10% as the discount rate because that’s my target rate of return.

Plugging the previously estimated dividends and those discount rates into my investment spreadsheet gives the following result:

Here’s a brief explanation of what that all means:

- Earnings and dividends per share are based on the same management targets as before

- The short-term and long-term dividend growth rates cover 2022-2030 and 2031 and beyond, respectively

- Good Value (£9.25) is the present value of GSK’s estimated dividends, discounted by 10% per year

- Fair Value (£17.44) is the present value of GSK’s estimated dividends, discounted by 7% per year

- Margin of Safety tells us where the current share price is between good and fair value (44% tells us it’s about halfway between the two)

Would I invest in GSK at the right price?

On balance, I would be happy to invest in GSK because it has a long history of success in its chosen markets and, given the scale, depth and breadth of its capabilities, I think it has the potential to continue succeeding for decades to come.

However, it does operate in very competitive markets and is success is by no means guaranteed, so I would only be willing to invest at a price that reflects those risks.

Based on the discounted dividend model above, over the next 12 months:

- I would be happy to buy GSK if its share price moved significantly closer to £9

- I would sell GSK if its share price moved significantly closer £17

- If I already owned GSK, I would be happy to hold at its current price of £13.80

If I did invest in GSK, the next decision would be around position size. In my case, I size positions based on a combination of the stock’s defensiveness and valuation.

In terms of defensiveness, the pharmaceutical industry is generally considered defensive because people get sick in recessions as well as booms. Personally though, I wouldn’t call GSK a defensive business. Its business model is fundamentally cyclical because each drug goes through a cycle, from development to patent-protected profitability to out-of-patent decline and eventually to full genericisation. So, as far as I’m concerned, GSK is cyclical.

Because cyclical companies usually have less reliable dividends, I give them a smaller default position size of 3% versus 4% for defensive stocks.

I then adjust that default size up and down based upon valuation, with cheaper stocks having larger position sizes (up to double the default) and more expensive stocks having smaller position sizes (down to half the default). This allows me to concentrate my portfolio around the most defensive and most attractively valued opportunities.

In GSK’s case, it has a margin of safety of 44%, which shows that its valuation is just above middling. As a result, my position sizing algorithm gives it a target position size of 2.8%, just below the default of 3%.

One final point is that we don’t yet have a set of annual results for New GSK minus its consumer healthcare business. When these are released in early 2023, I’ll revisit this review to see if my dividend model and valuation need to be tweaked.

Originally published by UKDividendStocks.com and reprinted here with permission.