The global monetary and fiscal stimulus implemented since the coronavirus erupted has been sizable, and policy-makers have acted with unprecedented speed. While it is recognised that this stimulus was necessary, the resulting increases in government debt and central bank liquidity have given rise to concerns that an upsurge in global inflation may be around the corner.

These fears are reinforced by evidence that globalisation is facing increased headwinds. With the recent blows of trade wars and the coronavirus, firms could begin to internalise their supply chains. Countries could increasingly close or restrict their borders and – in the name of ‘essential security’ – require key goods to be produced domestically. As a result, the efficiencies that globalisation has brought may be unwound, causing production costs to rise.

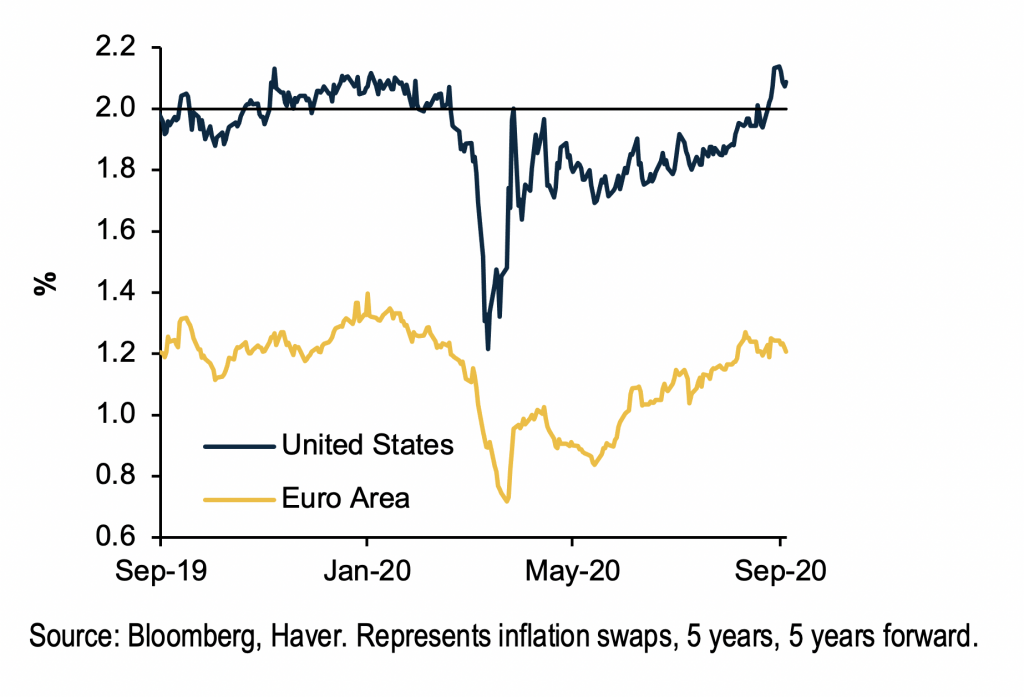

Figure 1: Inflation expectations

Inflation is becoming increasingly disconnected from money growth

Looking at a range of global data, there is little evidence to support such fears. In fact, inflation has become increasingly disconnected from money growth in recent decades, particularly since the global financial crisis. This is true in the advanced economies and, to a somewhat lesser extent, in the emerging markets. There is also find evidence suggesting that rather than fuelling demand for goods and services, and thus higher inflation, the rising money stock has driven demand for financial assets.

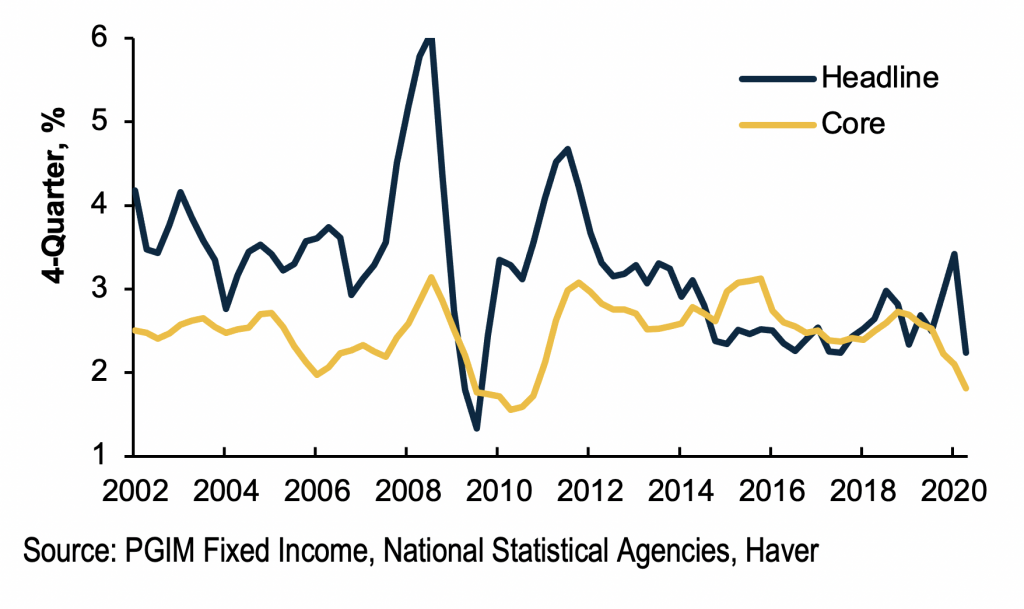

While recognising the inflationary risks, it must be emphasised that similar concerns were expressed in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. At that time, central banks’ balance sheets also expanded significantly and government debt levels rose. Observers warned of upward pressures on prices. But, global inflation – and inflation in most major countries – remained subdued (see figure 2). If anything, inflation ran a notch softer than in the years before the financial crisis, despite the efforts of some major central banks to push it higher.

Figure 2: Global CPI inflation

The real cost of high debt is disinflation, not inflation

For the advanced economies, our data suggests that heavier debt burdens have brought lower inflation and slower GDP growth. The cost of high debt is not inflation but rather disinflation and weak economic performance, reflecting increased uncertainties for the private sector. For the emerging markets, in contrast, higher debt levels do appear to be associated with increased inflation, but the relationship falls well short of statistical significance.

Based on our internal research at PGIM Fixed Income, we found a negative relationship between government debt and real GDP growth. This contractionary result could flow from weaker sentiment and spending among households and firms, as they struggle to assess uncertainties about future taxes and spending, the government’s ability to manage the debt, the sustainability of the debt over the longer term, and whether fiscal policy still has scope to stabilise the economy in another downturn.

To the extent that higher debt levels actually prompt fiscal retrenchment, the headwinds for growth are concrete and direct. In Japan, for example, high debt levels led to increases in the country’s consumption tax, which in turn created headwinds for growth. In the US, fiscal policy swung toward austerity after the financial crisis. This was implemented through a series of politicised fiscal cliffs and government shutdowns, which stoked uncertainties for the economy and markets. In Europe, fiscal policy in many countries was tightened appreciably following the peripherals crisis with an eye toward meeting the requirements of the Stability and Growth Pact. None of these countries have seen inflation break out on the upside.

We also recognize that the causality between debt and real GDP growth could flow in the opposite direction – countries with slower economic growth might over time accumulate higher debt burdens. Their slower growth could translate into weaker tax revenues and, thus, higher debt levels. Alternatively, some countries may seek to compensate for softening real GDP growth with increased fiscal spending. In short, soft economic performance (low growth and inflation) might result in higher debt levels, rather than the other way around.

What other factors have retrained inflation?

In addition to high debt levels, deep structural forces such as aging demographics, the advance of innovation and automation, and increasingly entrenched inflation expectations have driven inflation down and kept it low. The restraint from these factors could become even more pronounced in the years ahead.

- The aging of the population globally is sapping aggregate demand, weakening growth, and softening inflation. These factors have been clear and powerful in Japan, and other countries now seem to be following this path.

- Evolving technology and automation have restrained labour costs and product prices, especially for manufactured goods. Further, given advances in information technology and logistics, many firms now compete globally. This has limited their pricing power and restrained inflation. This effect has been powerful in retail, where firms must now compete against the so-called Amazon price.

- A generation are now coming to maturity who have seen only tepid price increases and low inflation expectations. This may actually be, in part, the work of central banks themselves. Previous generations of central bankers emphasised their determination to fight inflation. In retrospect, their efforts may have been too successful. The challenge today is figuring out the mix of tools and words to get inflation back up a notch. It’s possible that the Federal Reserve’s new framework will be a step in that direction.

As noted above, globalisation – another powerful disinflationary force – is facing headwinds. Even so, our judgment is that the forces bringing the world together are also powerful. While the pace of globalisation is likely to slow, we do not expect a broad reversal. Over time, a new synthesis will be hammered out that is more pragmatic, socially aware, and equitable.

The bottom line

A mix of structural factors working together have pushed global inflation and inflation expectations down – and are likely to ensure that price pressures remain muted in the years ahead. These factors generated sustained soft inflation in the decade following the global financial crisis and are likely to remain operative in the coming decade. Central banks across a range of countries will be leaning in the opposite direction, trying to push inflation up, but their task will not be easy.

For PGIM Fixed Income’s full analysis on global inflation, please see the Insights and Media section of PGIMFixedIncome.com for the white paper, “Is Higher Global Inflation Around the Corner?” (September 2020). For further discussion on trends in globalisation, please see our paper, “Globalization 2.0–A New Synthesis” (May 2020).