The rent is too damn high. So it’s natural that many entrepreneurs, socially-conscious investors, and real estate operators want to solve the housing crisis by building and financing affordable housing.

But “affordable housing” means different things to different people. To many, “affordable” is just a description of rent relative to local incomes. But for others—including most people in the housing industry and policy world—it refers to housing built and operated under specific government programs and mandated to maintain certain rent levels. So today we’re going to break it all down.

This letter we’ll explore the full spectrum of what it means to build affordable housing, from “naturally occurring” affordable housing to government-backed programs. Specifically, we’ll tackle:

- Workforce housing;

- “Affordable by design” formats: coliving, micro-apartments, ADUs, and other innovations;

- ESG affordability programs;

- Section 8 and LIHTC;

- Public housing;

- Cooperatives, land trusts, and other emerging models.

We’ll look at the pros and cons of each—and some of the opportunities within them—as well as the innovations and shifts that are happening in each category.

Note that this letter is tailored to people who are beginners at affordable housing and want an overview of the landscape; veteran affordable developers may find some interesting nuggets in here but today we’re going to focus on the basics.

Workforce Housing

The simplest kind of affordable housing is affordable not due to any government mandate or subsidy but simply due to local market conditions. If the local housing market prices a one-bedroom apartment at (say) $800 per month—due to a lack of demand, a surfeit of supply, or some combination thereof—most people would call that affordable housing. But most real estate professionals wouldn’t use that term here due to the potential for confusion with the formal affordable housing programs we’ll discuss later on.

Instead, real estate insiders use a lot of different names for this kind of housing supply: “workforce housing,” “market-rate affordable,” and “naturally-occurring affordable housing” are several. In many inexpensive, low-growth markets, most apartments are naturally affordable and fall into this category.

This is the easiest kind of “affordable housing” for a developer to get into, as it doesn’t require any special approvals or compliance beyond what’s normally required for multifamily. Of course, most developers enter the workforce housing market with a business plan that involves renovating units, improving conditions, and increasing rents. This can be a good business—and a positive for tenants when done well—but it’s somewhat at odds with the goal of providing affordable housing.

Given the popularity of value-add multifamily development over the past decade, it’s increasingly hard for multifamily sponsors to find market-rate workforce housing deals that haven’t already been “value added”. Usually, this means sponsors eager to get a deal done are looking at one of the following:

- Marginal locations. Hot Sunbelt markets have been picked over, but there might be interesting deals in Monroe, Louisiana or troubled parts of eastern Brooklyn.

- Small scale. Sponsors like Groma and Veritas have had (some) success rolling up portfolios of smaller (think 2-50 unit) assets that are too small for larger funds.

- Hair. Maybe it’s an environmental issue. Maybe there’s a title dispute. Maybe the Latin Kings have set up shop in the courtyard. In any case, other investors have passed, and there’s an opportunity for outsized returns for the brave or foolhardy.

Note that there are tax credit and incentive programs in some markets for preserving existing affordable units—such as New York City’s HPO program—but taking those will move a project to one of the government-subsidized buckets we’ll discuss later on with the added regulatory and compliance burdens.

It’s important to note here that’s we’re not talking about building affordable housing here. That’s because with today’s construction costs it’s very hard for affordable rents to pencil out with today’s construction costs without something else going on. We’ll cover that “something else”—affordable-by-design formats and ESG capital—in the following sections.

Affordable-by-Design Formats

Regular Thesis Driven readers know that I have some experience with affordable-by-design concepts. I used to run the largest coliving operator in the United States, so I’ve seen the opportunities—and challenges—that can come with these models.

Coliving

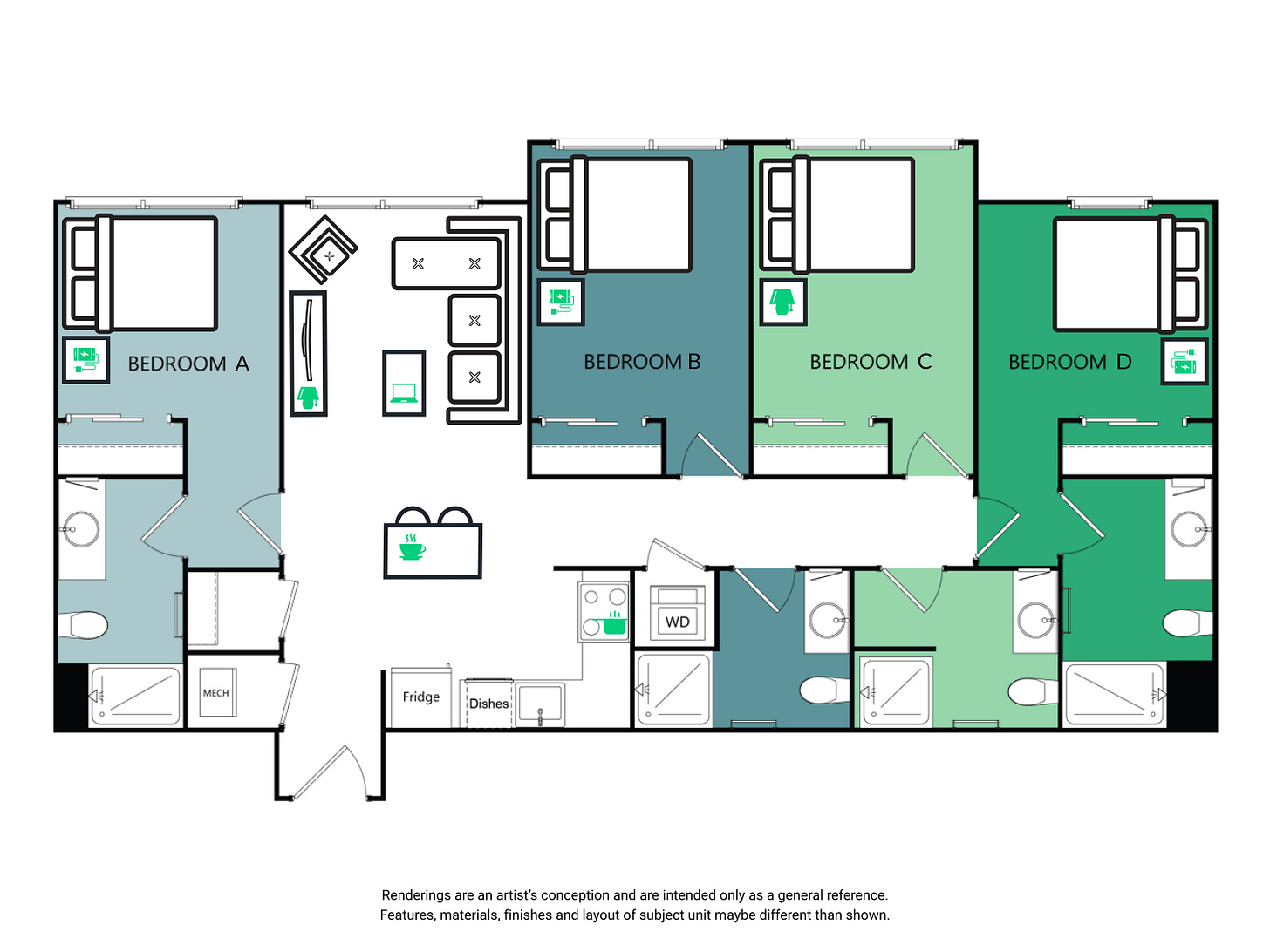

In the US, coliving implies units in which unrelated tenants have private bedrooms—and often bathrooms—but share kitchen and living areas. By increasing density, coliving can offer a “win-win” for tenants and developers with tenants paying well below studio apartment rents while developers see an increase in rent and NOI per square foot.

The challenge of coliving is that—in order to achieve those gains—assets must typically be built from scratch. While layouts vary, most coliving operators prefer 3- to 5-bedroom apartments, much larger than multifamily developers would normally build. These unique layouts make it challenging to finance new-build coliving assets and raise the yield premium required to build it, negating some of the affordability benefits.

Some operators have had success repurposing single-family homes, as they tend to have more bedrooms per unit. Bungalow and Padsplit both employ this model and have been able to scale into the thousands of bedrooms each.

Microapartments

Microapartments (frustratingly called ‘coliving’ in the UK and Europe) are simply smaller studio apartments of typically less than 400 square feet. Unlike a coliving room, each microapartment has its own small kitchen. However, microapartments typically don’t benefit from a shared living area; units usually open to a double-loaded corridor as in any other multifamily layout.

But the affordability benefits of microapartments versus typical studio apartments tend to be modest until unit sizes get quite small. After all, the most expensive parts of construction—the MEP and fixtures that come with kitchens and bathrooms—are just as costly in microapartments as they are in normal apartments. And unfortunately, the small unit sizes (<300 square feet) that can actually achieve real affordability are effectively illegal to build in most markets in the United States.

For a time—approximately 2009 to 2013—small microapartments were legal in Seattle, offering an interesting case study in affordability. Thousands of tiny units were delivered, some as small as 180 square feet. Those units remain an essential part of Seattle’s affordable housing landscape today, contributing to the city’s relatively affordable rents versus other tech hubs like San Francisco and Boston. Unfortunately, Seattle once again prohibited small microapartments in the mid-2010s.

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs)

We’ve written extensively on ADUs in the past, as they’re one of the fastest-growing segments of the broader affordable housing market today. In 2023, an estimated fifth of all new housing units produced in California was an ADU.

ADUs (also called “in-law units,” “backyard cottages,” “granny flats,” and a number of other names) are secondary residential units that occupy the same lot as a primary residence—often but not always a single-family home.

Legalizing ADUs has become a popular first step for states and municipalities looking to roll back exclusionary single-family-only zoning. Unfortunately, many ADU legalizations have come with poison pills such as hefty parking mandates and permitting fees as well as owner occupancy requirements that have limited their effectiveness. California is the main exception, where a series of laws have rolled back most ADU limitations, leading to rapid growth of the category.

For entrepreneurs without deep pockets looking to build affordable housing, ADUs can be a great option.

ESG Capital

As awareness of the housing crisis grows, more investors—both institutions and individuals—are viewing housing affordability as part of a broader ESG agenda. Affordability, therefore, is an investment objective alongside (or in replace of) financial return goals.

Given that financial returns and affordability are somewhat at odds, this ESG objective can take many different forms.

Social impact investing firm Calvert, for example, recently launched a $50 million affordable housing financing facility targeting “nonprofit and mission-driven for-profit” developers who wish to preserve existing affordable housing. The fund is administered by the Low Income Investment Fund, a CDFI serving minority communities.

Housing nonprofit and investment manager New Story is taking a different approach, using impact capital to buy and develop land in Latin America which is then sold to families at affordable rates. “We’ve seen firsthand how impact investment can drive innovative solutions in affordable housing,” said New Story founder Brett Hagler. “Investors are looking to us to address immediate housing needs while creating a blueprint for scalable, cost-effective solutions that can be replicated globally.”

For some investors, targeting affordability as a goal has a positive knock-on effect: housing with affordable, below-market rents (or for-sale prices) are less subject to macro swings in the housing market than market-rate units. For investors with a very long-term orientation, the benefits of stability and predictability complement the positive impact on society.

Government Programs: LIHTC and Section 8

When real estate industry professionals say “affordable housing,” they’re typically referring to housing developed with and/or benefitting from two government programs: Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) or Section 8. For the past few decades, these programs have been responsible for the vast majority of new deed-restricted affordable housing as well as subsidized affordable units.

Each is a complex program deserving of its own deep dive. (We spent a fair bit of time on LIHTC in a previous Thesis Driven letter on tax credit development last year.) Here’s the high level on each program, which partly draws from Hayden Glade managing partner Elliott White’s excellent talk at this year’s Reconvene:

Section 8

Section 8 (named after the relevant portion of the 1937 Housing Act) is a voucher program that pays a portion of the rent for low- and moderate-income families to rent units in the private housing market. Generally, tenants receiving Section 8 vouchers must make less than 50% of area median income (AMI). Tenants then pay 30% of their adjusted gross income toward rent with the balance paid by HUD through a Section 8 voucher. Over two million Americans benefit from Section 8 vouchers today.

There are two types of Section 8: (1) project-based vouchers which are tied to specific units and (2) tenant vouchers that follow residents from unit-to-unit.

Project-based voucher developments are “basically like public housing,” said White. “There’s an intense concentration of poverty,” particularly in markets with already low AMIs. Many existing project-based voucher buildings are smaller (<100 units) and in secondary markets. Buying them is “basically like buying a government contract,” notes White, adding that there are multiple types of Section 8 contracts with varying terms regarding rent growth, so buyers should be aware of what type of Section 8 they’re working with.

Tenant-based Section 8 vouchers, on the other hand, can theoretically be accepted by any building. In fact, many states—including New York and California—require that building owners accept Section 8 vouchers when asked by applying tenants. Notably, the rent paid by a Section 8 voucher for a unit is tied to the “fair market rent” (FMR) set for a given location and unit size by HUD and updated on a regular basis. In some cases, the FMR is known to exceed local market rents (“up to 2x in some places,” added White) providing a windfall for owners while draining limited housing voucher funds.

LIHTC

With over 3.6 million units built since 1987, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program is the most successful affordable housing program in the United States.

Unlike Section 8, LIHTC is a project-level tax credit program. Under the LIHTC structure, investors receive a dollar-for-dollar reduction in federal tax liability over a 10-year period in exchange for providing affordable housing.

To begin, there are two types of low-income housing tax credits:

- “9% credits” which are typically used to build new residential buildings. 70% of the construction cost of low-income units is covered by the credit. This credit cannot be paired with other sources of government financing such as tax-exempt bonds.

- “4% credits” which are typically used to purchase and renovate existing residential buildings. 30% of the construction cost of low-income units is covered by the credit. This credit can be paired with other sources of government financing.

The affordability requirements for LIHTC are complex and can be reviewed in more detail here, but in general 20-40% of a building’s units must be rented to households whose incomes do not exceed 50-60% of the area median income (AMI). While a building may include a mix of market-rate and LIHTC units, credits will only apply to the low-income units. In practice, most LIHTC developers dedicate most—if not all—of a building’s units to the LIHTC program.

The “9%” LIHTC program is competitive, with states regularly seeing more demand from developers than they have credits available. In the competitive process, state housing agencies will consider local housing needs, the sponsor’s track record, the levels of affordability proposed, and even the energy efficiency of the proposed project. (See example application from Idaho here.)

Unlike some other tax credits, LIHTC credits flow over 10 years and can only accrue to an investor or owner of the low-income property. Since many developers don’t have ongoing tax liabilities, tax credit investors are structured into the project as limited partners (“tax credit equity”). Tax credit equity often comes from banks and insurance companies with affordable housing investment mandates as well as future tax liabilities.

Unlike in market-rate housing development, LIHTC developers are generally not in it for the promote. Instead, LIHTC developers take a legally-regulated fee—usually 15% of construction cost—in addition to other management fees. Unlike in market-rate developers, LIHTC developers are attempting to maximize their fees versus the sale price of the unit.

LIHTC development is not for the faint-of-heart; there’s a significant learning curve on compliance and structuring. And the risk of a foot fault dropping the building out of compliance and jeopardizing the tax credit is real.

Public Housing

We’d be remiss to write an entire letter about affordable housing without at least mentioning how most developed countries around the world provide it: by having the government build and run it.

From Singapore to Sweden, large segments of the population live in government-built—and often government-run—housing. In many cases, these countries began their social housing building sprees in the early-to-mid 20th century and never stopped.

The story of public housing in the United States, of course, is less rosy. St. Louis’s Pruitt-Igoe—among the largest public housing complexes ever built—only lasted eighteen years before being demolished in 1972.

Social housing in Europe and Asia worked because the developments were able to capture working and middle-class citizens. While public housing in the US started that way—white New Yorkers made up the majority of NYCHA residents until the late 1950s—the complexes ultimately succumbed to white flight and midcentury turmoil, declining into intense concentrations of poverty by the 1970s.

Today, there are only around 800,000 public housing units in the United States today, about a quarter of which are in New York City. Public housing units are funded under Section 9 of the Housing Act of 1937, meaning they tap into a different—and far more neglected—source of funding than Section 8. Partly because of that, many public housing authorities now find themselves in dire financial straits.

New York City’s housing authority (NYCHA), for example, now faces a $78 billion repair bill stemming from decades of neglect. This has led authorities to propose creative solutions including rebuilding existing towers as project-based Section 8 developments through private development partners.

While some leftist state legislators occasionally make pushes for new social housing—California, for instance, recently passed a bill to study social housing—no serious plans to build new social housing at scale in the US are on the books. And federally the Faircloth Amendment effectively prohibits the construction of new public housing units using HUD financing.

So while public housing is the dominant affordable housing model worldwide, there’s little a social entrepreneur or advocate can do to make it happen—at least in the US.

Other Models

There are a handful of other new—and old—affordable housing models that we see from time to time, including:

Cooperatives

Just up the road from my place in Chelsea sits the Penn South Mutual Redevelopment Houses. While many newcomers mistake Penn South for public housing, it’s actually one of the largest housing cooperatives in the world almost 3,000 apartment units. While Penn South residents own their units, sale prices are intentionally kept far below market—although they rarely trade and have a long waiting list.

Penn South is unique due to being a “limited equity” cooperative borne out of the urban redevelopment programs of the 1950s, and it has since benefitted from significant property tax abatements. (The previous abatement, set to expire in 2022, was recently extended to 2052.) Caveats aside, Penn South is probably the closest the US has to Singapore’s successful public housing ownership model.

While the cooperative concept is often associated with affordable housing, there’s nothing inherently affordable about it—costs are still the costs. Penn South aside, New York is full of co-ops that are very far from affordable.

Community Land Trusts

Community Land Trusts (CLTs) are a trendy affordable housing model in advocate and nonprofit circles. In a CLT model, a trust owns the land while individuals or families can purchase or rent the homes built on it.

By separating land ownership from housing ownership, CLTs aim to protect the underlying land from market pressures and keep the housing affordable for future generations. Homebuyers in a CLT typically agree to resale restrictions, ensuring that homes are resold at affordable prices to future buyers. Vermont’s Champlain Housing Trust is perhaps the most successful CLT example to date: founded in 1984, it manages over 2,500 homes for low- and moderate-income families in Burlington, Vermont.

CLTs can combine nicely with the ESG capital discussed above; after all, some person or entity has to put up the initial capital to buy the land and (possibly) help finance development on it.

While there are a lot of ways to create affordable housing, each path has its own drawbacks and limitations, and different paths make sense for different operator profiles. A real estate veteran might be best suited to tackle Section 8 or LIHTC development as a GP, whereas a family office with an impact mindset might be better off sitting in an LP role or focusing on market-rate workforce housing.

In other words, there’s no one-size-fits all solution for either tenants or builders.

Ultimately, building affordable housing is attractive because of its potential to totally transform the lives of the people who benefit from it. There aren’t many other consumer products out there that have the magnitude of impact of providing housing to a family that might not otherwise have it. And that’s why it’s worth the struggle despite the headaches.

This article was originally published in Thesis Driven and is republished here with permission.