Not if it can generate income…

Originally published July 2022.

Mostly confined to cyberpunk and tech circles prior to 2021, the metaverse has since experienced breakout attention and entered the common vernacular. Not all of this has been welcomed. For every metaverse evangelist who emerges from the woodwork, so too does an equal and opposite detractor. Both archetypes tend to have very strong opinions about what exactly the metaverse comprises, often deviating from how it was originally characterised in Neal Stevenson’s 1992 novel, Snow Crash. In our recent research culminating in Unreal Estate: Metaverse, extended reality and the future of our physical world, we largely steered clear of this debate by focusing our analysis on the innovations in extended reality and virtual space that symbolise a disruption to the way we use and interact with our physical spaces.

The virtual land rush

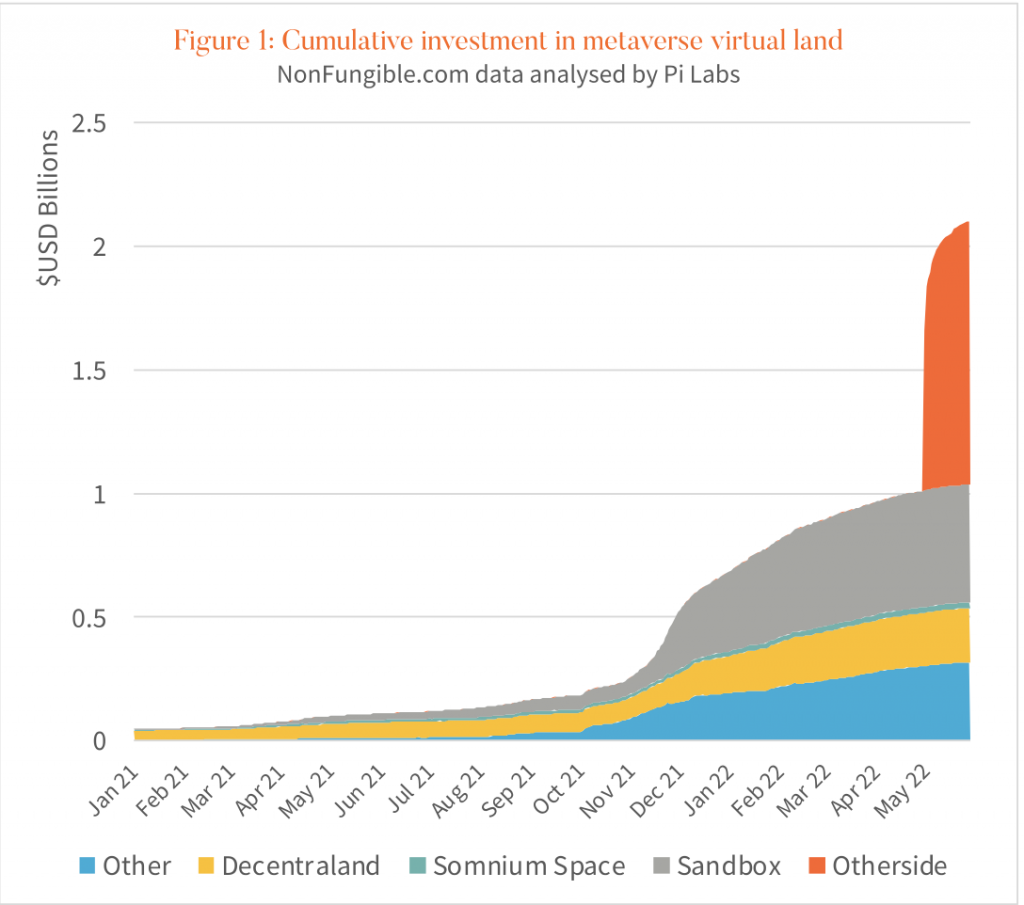

Key ingredients of metaverse hype have been the launch of, or investment upswing within, virtual platforms such as Decentraland, Otherside, Sandbox, Somnium Space, Voxels, Super World and a list of others. On many of these platforms, participants can purchase virtual land and create experiences on them. More recently, we have seen mass virtual land speculation: $2bn of virtual land changed hands during the April 2022 launch of Otherside (see figure 1), causing the Etherium blockchain network to temporarily crash and prompting fees to skyrocket for processing the transactions, even if they didn’t go through. In the context of real estate, this would be akin to paying stamp duty before buying an asset, whether the deal goes ahead or not. The word ‘speculation’ is often used in tandem with a criticism that there has been limited proof-of-concept on these platforms, evidenced by the abysmally low level of user activity in some cases.

Value beyond speculation?

A natural question for valuation professionals and sophisticated investors has emerged in recent months: is there any reasonable justification for the prices paid for virtual land on these platforms or is it all just another example of greater fool theory? As discussed by my co-author on this project, Andrew Baum, in his recent article in The Property Chronicle on the metaverse, real estate professionals are familiar with three valuation methods: direct capital comparison, the cost approach and the income approach. Direct capital comparison has limited efficacy in the metaverse if you prescribe to greater fool theory. As Andrew puts it, the cost approach has enough limitations in the physical world for which it was designed. The income approach, however, can be contemplated from various angles. The angle we took was to identify the customer acquisition cost of a would-be buyer of metaverse land and value the plot based on the foot traffic, the projected growth in foot traffic over time and the percentage of passers-by one could reasonably expect to complete a transaction on the plot. All of this hedges on another fundamental question: what exactly are users doing in the metaverse? In other words, what could a virtual landholder do with their plot to access consumers?

Metaverse use cases

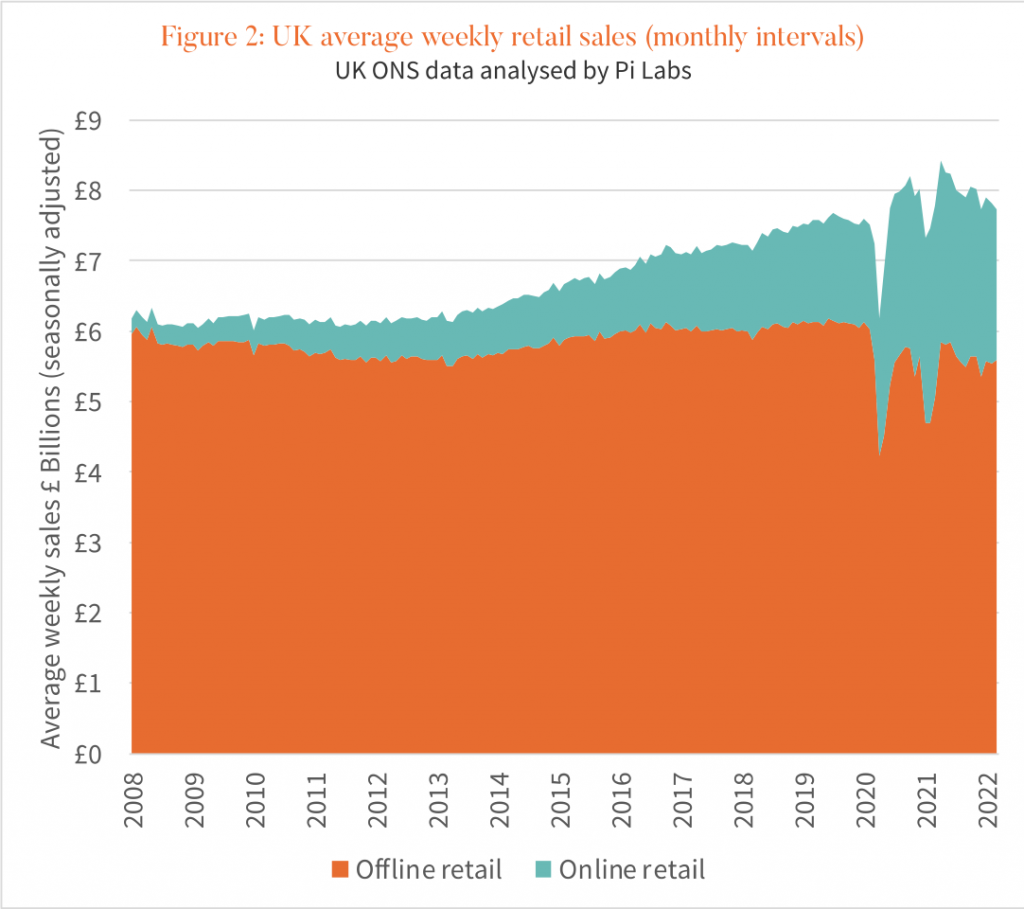

To illustrate a discounted cash flow approach to virtual land valuation, the paper includes the simplified case study of a fashion designer who is accustomed to spending £4 to acquire each customer. In this hypothetical exercise, the virtual land plot in question is worth £424,185 to them. However, a problem emerges. This valuation exercise relies on several assumptions about where the metaverse is headed. This uncertainty should impact the discount rate used in any attempt to value virtual land, and it should also prompt buyers of virtual land to contemplate how people are using the metaverse now and how it may be used in the future. In February 2022, for example, Decentral Games’ ICE Poker virtual casino was purported to be hosting around 30% of Decentraland’s daily users. Gambling, or more broadly, gaming, is a recurrent theme across the metaverse. Some argue that the only platforms gaining meaningful traction are associated with gamified experiences. Sandbox is often referred to as the ‘Minecraft of the metaverse’ and Otherside promises to serve as a world complete with a ‘biogenic swamp’ at the centre, ‘infinite expanse’ at the periphery and enigmatic creatures called ‘Kodas’ throughout (…although ‘Kodas’ might spook the casual gamer, no doubt ‘infinite expanse’ is what makes property investors tremble). When Facebook (now Meta) acquired virtual reality (VR) headset creator Oculus in 2015, one of the most salient criticisms from the VR community was that Facebook would transform the technology from gaming to social. This appears to also include the workplace, with Meta’s sights clearly set on the ‘virtual private office’. With people spending more of their professional and personal hours online, our report argues that this creates an opportunity for monetising how people present themselves as in the physical world, i.e. virtual fashion. This means we should expect to see more occurrences akin to the purchase of $4,000 virtual Gucci handbags. If consumers are buying virtual fashion via metaverse platforms, what will stop them from buying physical goods there too? Already we know that nearly all growth in UK retail can be attributed to online channels over recent years (see Figure 2 below). On the other hand, perhaps metaverse innovations will be used to enhance physical spaces and attract consumers back to brick-and-mortar. Either way, ignoring the metaverse won’t make it go away.

Is it anything more than hype?

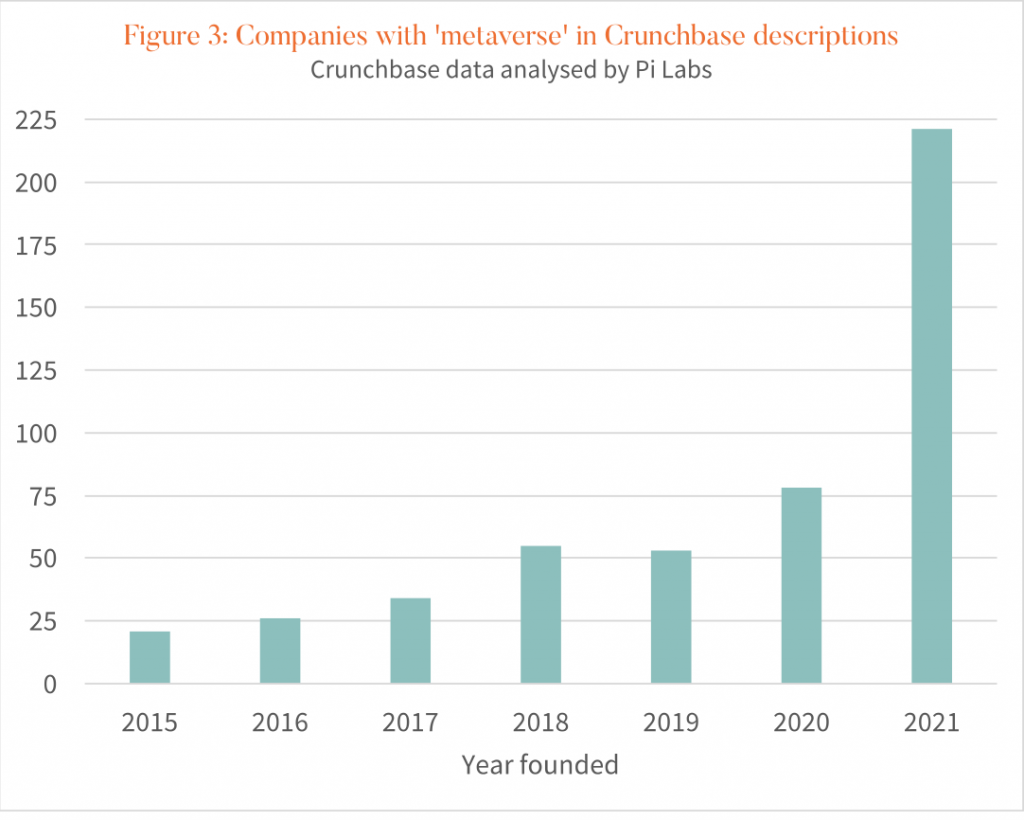

According to Bloomberg, ‘metaverse’ was mentioned once in their sampling of company earnings reports in Q2 2020, four times in Q3 2020, nine times in Q4 2020, 37 times in Q1 2021, 100 times in Q2 2021 and 449 times in Q3 2021. Crunchbase has also seen an upswing in use of the term, with breakout activity within new company descriptions in 2021 (see Figure 3 below). This speaks to the emergence of detractors mentioned earlier in this article. It’s hard to argue that this looks like anything other than tulip bulb mania. The metaverse’s reputation isn’t helped by the fact that metaverse-linked currencies such as MANA experienced an overnight price boom the moment Mark Zuckerberg renamed Facebook to Meta. MANA has since steadily declined toward its pre-hype level. However, what metaverse detractors often neglect to acknowledge is the persistent association younger generations have with their online identities and activities. According to a survey by The New Consumer and Toluna, 45% of Generation Z feel more like themselves online. One might associate this with their youth, but the figure for Millennials is a strikingly close 43%.

Where to from here?

There are a growing list of metaverse projections—with examples including $426.9 billion market size by 2027; $1 trillion of annual revenue opportunity (no date given); and $1.6 trillion market size by 2030. As with other metaverse talking points, projections will in part be determined by what forecasters define as the metaverse today, and what they expect it to include into the future. In the world of real estate, one barrier to adoption could be the current state of the global economy. Our survey of 151 mid-to-late career real estate professionals found a gap between those who expect the metaverse to impact real estate in the coming zero-to-four years (46.3% of respondents) and those whose organisations are doing something about it (21.9% of respondents). A common theme that emerged was ‘real estate has bigger problems to deal with this year’. Despite this, we are seeing the beginning and continuation of highly ambitious metaverse-related projects in real estate, such as the wearable immersive real estate dataroom (WIRED) collaboration between BNP Paribas Real Estate and Unity 3D, as well as the in-roads Pi Labs portfolio companies such as Moonhub, Contilio, Bright Spaces and Dent Reality have recently made with large real estate brands.