UK legislation enforcing minimum emissions standards for existing buildings can no longer be ignored

“A change in the weather is sufficient to recreate the world and ourselves,” or so said Marcel Proust 99 years ago. I wish he had explained this to the property profession. For the last three years I have been travelling the UK, urging them to address the need to retrofit existing buildings to comply with new energy efficiency rules. Until the introduction of the new legislation in April 2018, most players in the markets affected simply ignored it, and prices continued to be oblivious to energy efficiency.

In 2016, the UK signed up to the Paris Agreement (building on the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change) to reduce its carbon emissions to 80% of 1990 levels by 2050. As property carbon emissions are estimated to account for 50% of the UK total, addressing energy efficiency in buildings is central to meeting this target.

It is an ambitious target, but the market had already adapted on energy efficiency for new developments; the battle to provide new efficient buildings has largely been won. The UK’s 1990 BREEAM initiative of certifying buildings for sustainability – in the UK and worldwide – has led to occupiers of new buildings demanding the highest ratings. This, in turn, has led developers to ensure their buildings are sufficiently sustainable. The problem was with retrofitting existing stock. But even here, the government was already planning the introduction of legislation for the rented sector to “encourage” landlords to make their properties energy efficient.

The new legislation, known as the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES), applies to all investment buildings, domestic or non-domestic, and it is now illegal to let buildings on new leases with the lowest two EPC energy efficiency ratings, F and G. This is far-reaching legislation and it isn’t transitionary – it’s a game-changer. It won’t only affect pricing and valuation but all aspects of the property market. The nature of leases, dilapidation settlements, bank lending, property management strategies and investment portfolio selections will all be affected by MEES. Full details of the legislation can be found on the RICS website in its insight paper Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES): Impact on UK Property Management and Valuation.

The UK has some of the oldest building stock in the world. Although many have high energy efficiency ratings, others will need substantial retrofitting to meet the ever more stringent regulations. Measurement of efficiency is done through the energy performance certificate (EPC) system, which rates buildings from A to G, with A the best. EPCs are a regulatory requirement for all properties being sold, rented or built. They were originally intended as a carrot to entice buyers and occupiers to demand higher-efficiency buildings for the sake of lower energy bills. Many saw them as an integral step towards a greener UK, but without any urgent impetus or legal requirement to improve efficiency, they proved ineffective.

The government recognised that a stick rather than a carrot was needed if it was to meet its internationally agreed carbon targets by 2050. This meant new legislation, restricting occupation – and it decided to concentrate its initial efforts on the property investment market, in other words landlords. In short, MEES was introduced to encourage the retrofitting or redevelopment of energy-inefficient buildings. In theory, poorly rated properties would either be retrofitted or redeveloped (or temporarily exempted) and the lowest ratings, F and G, would soon disappear from the main markets due to the laws of supply and demand. E-rated property would subsequently also be designated as non-compliant, then D and C and so on, until by 2050 all let properties would be A rated.

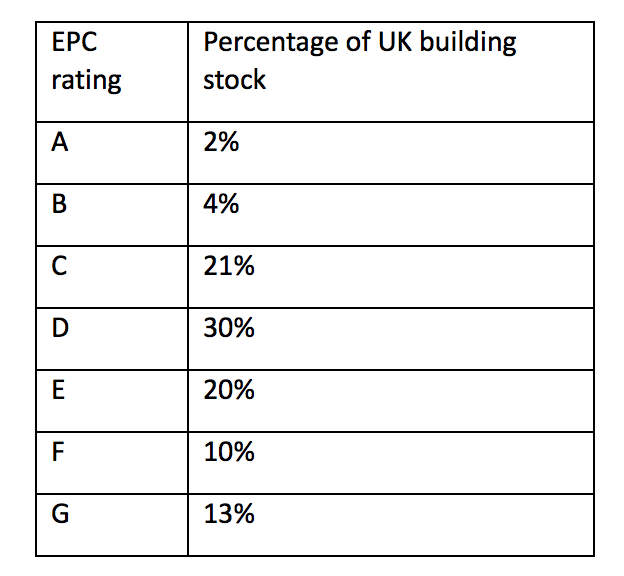

According to 2016 figures from the Green Construction Board, the approximate breakdown of all properties by EPC ratings is:

The intent to get all rented properties to an A rating by 2050 was based on the government’s overall target of reducing total UK carbon emissions to 80% of 1990 levels, which is still a relatively high level. However, in June 2019, the UK government announced a new target: to become carbon neutral by 2050. While there is talk of offsetting carbon emissions with tree plantations and carbon capture projects, there is no denying the new target will have an impact on the MEES legislation. In my view, it will lead to the timetable for achieving universal A ratings becoming more draconian and the policing of this more rigorous.

The exclusion of F and G ratings is just the start. Some forecasted targets have suggested that E ratings will have to be excluded by 2025, D by 2030, and C by 2040, leaving all property as A-rated by 2050. It seems that this will now be speeded up.

There is also a likelihood that the way EPCs are calculated will become more stringent and detailed. A property currently rated as, say, C may when reassessed fall into the F or G category. Even without the MEES legislation capturing more ratings as non-compliant, this will result in more properties falling foul of existing legislation.

MEES is having a significant impact on all aspects and areas of the property market. Yet many commentators question the importance of a small nation like the UK, which contributes less than 1% to the global carbon emissions through its building stock, imposing such drastic measures. If all countries were doing the same, it would be an even playing field. But as they are not, the argument is that the UK is imposing unnecessary costs and regulation on UK plc.

That would be true if you view MEES only as a restriction; an unnecessary cost. But there is a flipside: this is about improving efficiency and reducing on-going costs. It is agreed that initially MEES will impact negatively (a ‘brown discount’) on the value of energy-inefficient properties but, over time, occupiers will start seeing lower energy bills as efficiency increases, and the value of such properties after retrofitting will begin to increase (the green premium) as the market reverts to pricing running costs as part of the overall occupation costs.

We are in a period of transition in the market, but against the background of legislation, regulations and EPC algorithms that are also in flux. This is a difficult period for property professionals, who are providing advice on a foundation of shifting sands. All property professionals need to be fully conversant with MEES legislation and work in tandem with EPC assessors to provide strategic advice to investors. All advice, all valuations, all legal interpretations must take account of MEES.

So, what does this all mean? It’s a change of sea level, if you will pardon the pun: the UK property market will never be the same again. Everyone who works in the UK rented property market will be affected by the MEES legislation. Property prices will fall, property management will become more complicated and the enforcement of the legislation will become stricter. At the start of this article, I said that prior to the introduction of MEES, the property market should have started addressing the forthcoming legislation years ago. Indeed, everything that is happening now should have happened prior to its implementation, but markets have a way of ignoring consequences until the last minute. They are not ignoring it any more.