After 39 years working as a journalist, and 17 years as the head of Sky News, John Ryley retired in May. In a series of articles for The Property Chronicle he reflects on how the news business has changed and how it will develop in the future.

“It was a bright cold day in April and the clocks were striking thirteen…”

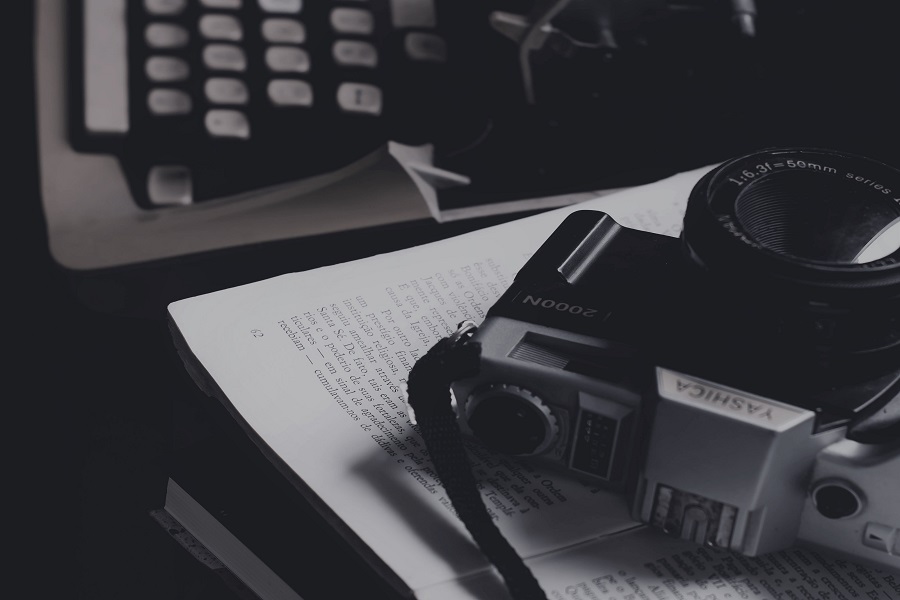

It was 1984. I had spent the last three happy years studying Latin at Durham university, where I was able to translate, analyse, and dissect anything written by Tacitus, Horace, or Lucretius. However, I was totally unable to spell, punctuate, drive a car, or use a typewriter. So, naturally, I started to look for a job in journalism.

It’s now almost 40 years since I started work as a journalist. As well as looking back on those four decades working in the news industry, in this article series I intend to peer into the future 40 years from now and try to imagine what the news industry will look like in 2063…

Breaking news from 1984

George Orwell wrote “Nineteen Eighty-Four” in 1948 at the start of the Cold War – arguably now the “first” Cold War. Orwell peered into the future and saw a grim world of Newspeak, Doublethink and Big Brother.

1984 was a huge year for news – it was the year of the Miners’ strike led by the leader of the National Union of Miners, Arthur Scargill, which would be Britain’s most socially divisive industrial dispute for nearly six decades. It was the year that the IRA tried to assassinate Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, along with her entire cabinet in the Grand Hotel in Brighton. It was the year when Britain was threatening the European Community with dire consequences if it didn’t get a better deal on its EEC budget contributions.

Overall, it was a year when the country was deeply divided; strikes were bringing the country to a halt, Westminster was obsessed with Europe, and there was a continuous threat from terrorism. 40 years on, it seems that things are pretty much the same, except with the addition of a new, much more existential threat from a dramatically changing climate. But the big themes for news organisations remain; social divisions at home, competition with Europe, and international crises abroad.

However, the news business – in fact, the entire world of journalism – has changed significantly. In 1984, TV news was enjoying a boom, with ITV and BBC news programmes attracting an aggregate audience of more than 20 million people. However, around eight in ten British homes took a daily paper and even more had one delivered on a Sunday. Many had predicted that TV would kill off newspapers, but it has yet to happen.

There was one very strange thing about the news industry in 1984; in many ways it was stuck in Groundhog Day, having changed very little from the way it was in the 1960s. Yes, Britain’s best known flagship news show – ITV’s News at Ten – was in colour, but otherwise, the programme looked and sounded much the same as it had done when it launched in the summer of 1967 with two presenters sitting behind a desk for half an hour.

National newspapers were still being put together by vast numbers of printers using cumbersome Victorian-style linotype machines. The papers were bundled up by a different group of highly paid people belonging to a different union and dispatched round the country by rail and road. The Wapping dispute was still to come, triggered by the media tycoon Rupert Murdoch bringing in more modern and less labour-intensive web offset printing. Arguably, Murdoch’s action saved national newspapers from financial ruin.

The newsroom

At the time, mobile phones were in their infancy, but they were the playthings of the rich. They were far too big and heavy, and far too expensive to risk giving to irresponsible journalists. Computers were starting to replace typewriters in newsrooms, but they often malfunctioned – we kept our typewriters as a backup under the desk.

Tim Berners Lee had not yet invented the World Wide Web. If you wanted information for a news story you did what journalists had been doing for years; you got a file full of yellowing newspaper cuttings from a department known as “News Information” (also known as “The Morgue.”)

An Orwellian characteristic of the news industry back then was the power of the trade unions; TV – like the newspapers – was literally a closed shop. Multi-skilling was impossible. You had to be in the right union to do the job. If a journalist so much as picked up a camera or touched an editing machine, members of the all-powerful technical union (the ACTT) would have been out on strike in seconds.

Don’t let anyone try to tell you it was a golden age; it most certainly was not. Newspapers and TV news programmes – the “products” – and the means of distributing them, had barely changed at all for two decades. But over the 40 years since then I have witnessed a remarkable revolution in the news industry. The velocity of that revolution has been breath-taking, especially over the past dozen years since the arrival of broadband, mobile internet and all the technology that flows from it.

As a recent head of GCHQ said, the growth of the internet has already been the biggest migration in human history. New developments happen so quickly that it is often hard to know what next week will bring, let alone next month, next year, or next decade; and it’s going to go on for many years to come.

2063 may sound like an eon away. But I’m going to do what no journalist should ever do – I shall peer into the future and rampantly speculate…