The constraints of newspaper reporting helped hone the style of many great novelists, including Hemingway

Before they were literary celebrities, many authors spent time as jobbing journalists. Charles Dickens, Rudyard Kipling, H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Rebecca West, George Orwell, Winifred Holtby, Graham Greene, Ian Fleming… the list goes on, all worked for newspapers and magazines not only to earn a living but also to hone their skills as wordsmiths. Today, whether in good old-fashioned hard copy or via the internet, radio or TV, journalism can still play an important part in a creative writer’s development, as can be seen in the career paths of Stieg Larsson, Robert Harris, Sarah Breen, Emer McLysaght and Tony Parsons.

Being a journalist invariably means having to work within strict word limits to immovable deadlines and in a specific style tailored to the interests and sensibilities of a particular readership. These constraints teach the budding writer the importance of an economic use of language, self-discipline and how to hold a reader’s attention – all essential skills for anyone hoping to become a professional, commercially successful storyteller. However, whilst journalism has played a crucial role in developing many writers’ skill sets, it also shaped what we’ve come to recognise as the modern novel.

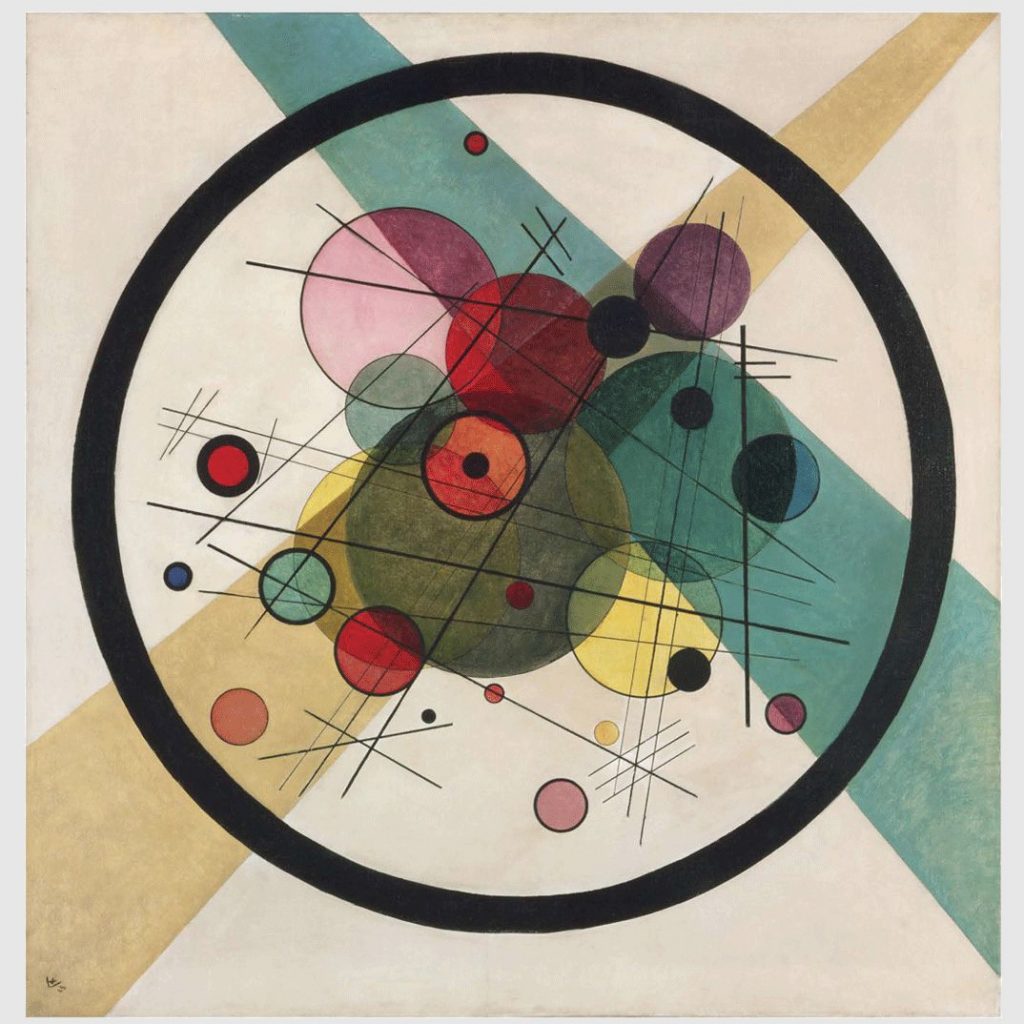

Modernism, the ‘undecorated’, minimalist forms of art, music and architecture that better reflected the reality of life in the industrial societies of the US and Europe, began to gain traction in the early part of the 20th century. In architecture, a modernist, functional style was developed at the Bauhaus design school (1913-33), an understated, non-representational form of music could be heard in the works of Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), and in visual art, painters such as Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) developed a geometric style where ‘meaning’ was not obvious.

Many of the principles of modernism would also be adopted by writers, including James Joyce, Dorothy Richardson and Ernest Hemingway. To create a greater sense of realism, they used techniques such as replacing the traditional omniscient narrator’s point of view with an interior monologue where the protagonist shared their inner thoughts with the reader. This is very familiar to us now but would have seemed radical to the reading public of the 1920s.

The way in which the modernist writers used language changed too. Greater authenticity was achieved by cutting out florid, poetic prose piled high with adjectives and adverbs, leaving much to the interpretation of the reader. This was an approach which also served the minimalist credo that ‘less is more’. Hemingway based his vision of modern literature on what he called his iceberg theory. This ensures that a story’s main themes remain underlying and that the thoughts of its characters stay largely hidden beneath the surface. Even on those occasions when we are afforded access to the feelings of the protagonists, it is usually just a glimpse.

For example, compare these extracts from novels both published in 1927:

“The April night was clear and chilly and a brisk wood fire burned in a welcoming hearth. The book cases which lined the walls were filed with rich old calf bindings, mellow and glowing in the lamp light. Some big bowls of scarlet and yellow parrot tulips beckoned banner-like from dark corners. The doctor had just written his acquaintance down as an aesthete with a literary turn, looking for the ingredients of a human drama, when the manservant re-entered.”

– Dorothy L. Sayers, Unnatural Death

“In the autumn, the war was always there but we did not go to it any more. It was cold in the autumn in Milan and the dark came very early. Then the electric lights came on and it was pleasant along the streets, looking in the windows. There was much game hanging in the shops and the snow powdered in the fur of the foxes and the wind blew their tales.”

– Ernest Hemingway, In Another Country

Even allowing for the difference in genre, Sayers’ traditional prose style is far more prescriptive and explicit than Hemingway’s. It controls and directs the reader by providing copious amounts of detail including what the characters are thinking, leaving little room for the imagination to work on the text. In Hemingway’s unadorned modernist piece, however, the bleakness and menace of the First World War is only implied, hinted at; it is a spectre haunting the steps of the characters. What is omitted has a greater power than that which is stated.

Having been interested in journalism even at school, Hemingway worked as a news reporter and foreign correspondent before he was a successful novelist, and the iceberg theory neatly explained his already established style of writing. Events, usually with little context or explanation, are the focus of much of his work and that of the modernist writers who emulated his highly influential style; an economic, clear reporting of the facts where profound truth lurks below a story’s more obvious surface and simple words can be charged with meaning.

Hemingway was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1953 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954, the Nobel committee acknowledging his “forceful and style-making mastery of the art of modern narration”. He himself said that a writer’s style should be “direct and personal, their imagery rich and earthy and their words simple and vigorous”. What is this if not a definition of great journalism? Hemingway and the many other novelists who worked for newspapers and magazines always acknowledged the debt they owed to journalism, and how it taught them to pare back their prose to its essential, concise best.