Summary

- Xaar is a relatively young and small leading-edge technology business which I bought in mid-2018

- It’s a good example of how excessive R&D in highly cyclical businesses can produce bad results

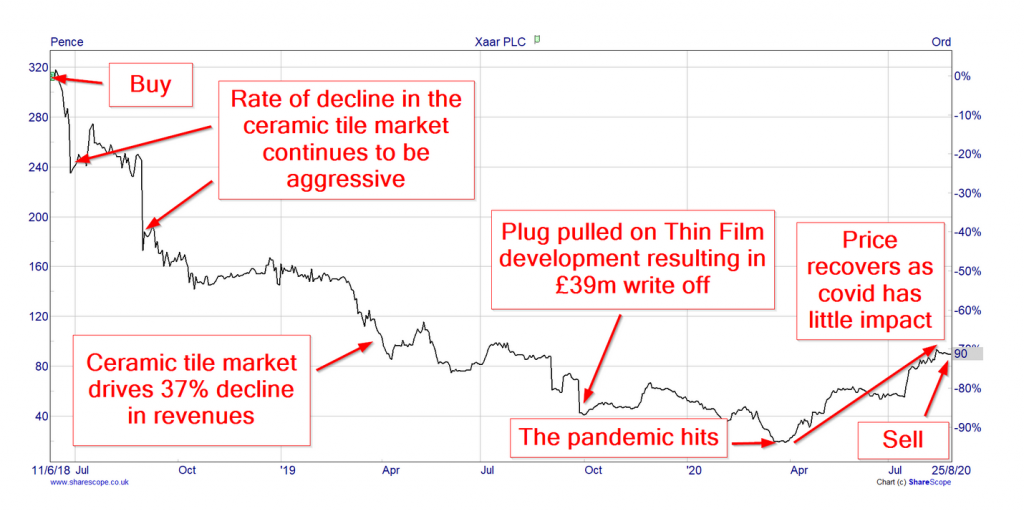

- I sold because a 90% increase in Xaar’s share price since November means the company is no longer obviously cheap

- Although Xaar was a bad investment it has helped me define the boundaries of my comfort zone, which is defensive value stocks

When Xaar joined my portfolio in June 2018 I knew it was close to the edge of what I felt comfortable investing in. Unlike most of my investments, which tend to be fairly large, established market leaders, Xaar was a relatively young disruptive technology business with a track record that was relatively short and inconsistent.

It was set up in the 1990s to commercialise digital inkjet printing technology and, by 2013, had grown substantially to peak revenues of £140m. When I invested in Xaar its revenues had declined from that peak, but it looked as if the company had turned a corner and returned to growth.

But I was wrong. Xaar’s results became consistently worse through 2019, eventually leading to massive writedowns, huge losses and the departure of the chairman, CEO and CFO. As a result of Xaar’s rapid decline, I carried out a thorough review of the company and my investment process in November to see where both Xaar and I had gone wrong.

That review reaffirmed my preference for “defensive value investing”, which to me means investing in:

- a diverse portfolio of

- market-leading businesses with

- long track record of consistently high profitability driving

- sustainable inflation-beating growth thanks to

- durable competitive advantages.

In the rest of this post-sale review I’ll outline why I bought Xaar in the first place, what went wrong and why I no longer think Xaar is a suitable holding for a defensive value portfolio.

I bought Xaar because it was highly profitability, had grown substantially and seemed to be attractively valued

As I’ve just mentioned, Xaar was created in the 1990s to commercialise potentially disruptive digital inkjet printing technology. Initially Xaar achieved this by licensing its patented know-how to printer manufacturers for a fee. After a while, Xaar acquired manufacturing facilities and started to manufacture inkjet printheads for commercial and industrial printer OEMs (original equipment manufacturers).

Xaar was successful and grew, somewhat lumpily, to peak revenues of almost £140m in 2013, driven largely by the ceramic tile printing market as it converted to digital printing. When Xaar joined my portfolio in 2018, those revenues had fallen back to £100m as the ceramic tile printing market matured. My assumption at the time was that the ceramic tile market would stabilise, with Xaar retaining significant market share following the initial transition to digital printing.

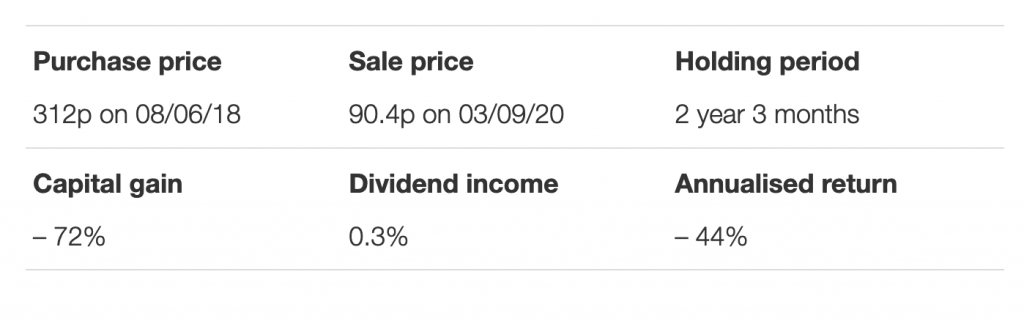

Here’s a snapshot of Xaar’s financial results when I bought it in mid-2018:

Despite volatile 2012-2015 results, Xaar seemed to have produced long-term growth

The chart above shows how revenues and especially earnings exploded upwards as the ceramic tile printing market switched to inkjet from around 2010 to 2013. That boom was then followed by an inevitable decline in sales as the transition came to an end. This is normal because once most end users have switched to digital printing, they don’t need to upgrade their printheads for several years. When I bought Xaar in 2018 it looked as if its revenues had already stabilised and started to recover.

The chart also shows that capital employed was the only metric that consistently went up. That was driven by heavy R&D investment into Xaar’s groundbreaking Thin Film technology. Thin Film was supposed to help drive the company towards revenues of £220m by the year 2020, but instead in nearly drove Xaar off a cliff (I’ll have more to say on that shortly).

The rapid increase of capital employed, combined with Xaar’s declining post-2013 earnings, meant that return on capital employed had declined to less than 10% by 2017. At the time that was a mild red flag as I don’t like to invest in companies where return on capital is below 10%.

However, Xaar’s average return on capital for the decade was above 10%, thanks to super-normal earnings from 2012 to 2014, so I wasn’t overly worried about what could be just a short-term decline in profitability. The company also had no debt and few lease liabilities. Both of those are attractive features for most businesses, but they’re near-necessities for relatively young and volatile technology businesses like Xaar.

One other thing I liked about Xaar was its position as the world’s leading pure-play digital inkjet manufacturer. While there were bigger printhead manufacturers out there, none specialised purely in digital inkjet. But what I didn’t realise at the time, was that being the world’s leading pure-play competitor is a relatively useless accolade.

Why? Because it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re the true market leader, so it doesn’t necessarily have any of the advantages of true market leadership (most of which relate to scale and brand awareness).

Xaar soon ran into some very serious problems

Shortly after Xaar joined my portfolio in mid-2018, management announced that sales into the ceramic tile printing market were falling much faster than expected. Soon after that the dividend was suspended, and then in late 2019 Xaar announced a seriously bad set of results. Revenues were down more than 36% and profits had turned to losses of £52m.

More importantly, management announced that they had effectively run out of cash to fund the remaining development and industrialisation activities required to bring Thin Film technology to market. All Thin Film R&D activities were cancelled, and the value of related equipment, inventory and R&D were written down by £39m. That was a major blow and any thoughts of Xaar achieving its goal of £220m of revenues by 2020 went up in smoke.

Unsurprisingly the CEO, CFO and chairman left soon after and a new CEO was given the task of understanding what went wrong, fixing the problems and turning Xaar around.

The speed and severity of Xaar’s decline surprised me, so I decided to review the situation to understand:

- why Xaar had collapsed,

- whether I’d missed any red flags in my purchase review and

- whether Xaar should stay in my portfolio or be sold immediately

What follows is an updated summary of my post-disaster review of Xaar, which I first published in November 2019:

1) Why did Xaar collapse?

The root cause of Xaar’s decline was a mismatch between the amount of cash needed to fund the development of its new Thin Film technology and the amount of cash generated by existing product sales. This mismatch was driven by a rapid decline in Xaar’s revenues after 2013 and a far less rapid decline in its R&D investment.

For example, in 2010 Xaar spent £4.7m (about 10% of revenues) on R&D. By 2013, revenues had grown to £137m and R&D investment had increased to £16.4m, or 12% of revenues. By 2016, R&D had climbed to £22.4m. However, revenues had declined to £76.2m as the ceramic tile market’s transition to digital printing came to an end.

£22.4m of R&D was clearly unsustainable as the company was only generating £10m of operating cash. In fact, investment in R&D, acquisitions and capex was running at more than £30m. As a result of this excessive R&D, Xaar’s cash reserves were shrinking.

By mid-2019 it became clear to management that:

- revenues were going to decline to around £50m

- profits from Thin Film printheads were years away

- Xaar could not afford the remaining Thin Film R&D and industrialisation costs

As a result, the revolutionary Thin Film technology which was supposed to turn Xaar into a £220m revenue company had instead almost killed it. But I don’t think this crisis was even remotely inevitable.

In my opinion, management became fixated on reaching their “vision” of achieving £220m revenue by 2020. To reach that goal, they knew Thin Film products would be absolutely necessary, so they continued to fund Thin Film development even as it became clear that Xaar didn’t have the funds to bring it to market. They then announced that Xaar would need a strategic partner to share the costs (and benefits) of bringing Thin Film to market.

However, as the months ticked by no strategic partner appeared, and yet the company continued to invest heavily in launching Thin Film. They even signed up three major Thin Film customers, even though Xaar lacked the strategic partner it absolutely required.

Soon after that, Xaar simply ran out of cash to fund its Thin Film dream any longer. Many people lost their jobs and Xaar had failed in a very public and brand-damaging way. In my opinion this could have been avoided if management had not been so focused on achieving their goal of £220m in revenues by 2020.

I think Xaar’s management should have scaled back R&D in line with the company’s post-2013 revenue declines. That would have set the Thin Film programme back by several years, but it would have kept it alive and would also have allowed more cash to be reinvested into the existing core business and core products. In addition, I don’t think management should have signed customers up for Thin Film products knowing that they wouldn’t be able to fulfil those orders without a strategic partner, which they didn’t have.

Management were, in effect, crossing their fingers and praying for a knight in shining armour to appear. And unfortunately for everyone involved, their prayers went unanswered.

2) Were any red flags missed in the purchase review?

There were two main drivers of Xaar’s collapse:

- dramatically declining revenues and

- management’s decision not to cut R&D funding

I don’t think it was obvious that management were going to keep funding R&D even when cash flows were obviously insufficient to support it, so I’ll focus on Xaar’s declining revenues.

Red flag 1: Management’s lack of caution during an unsustainable market boom

In my original purchase review of Xaar (PDF), I said the boom and bust in the ceramic tile printing market could lead to “massive investment in supply capacity (factories, machinery, etc.) which is then left underutilised once demand collapses, with the risk that it becomes an expensive white elephant”.

That’s a pretty good description of what eventually happened. To me, it suggested that management were possibly over-optimistic, short-sighted or too focused on their growth target. I would call this a mild red flag and with hindsight I should have paid more attention to it.

Red flag 2: Rapidly declining revenues and earnings over several years

A much larger red flag was the dramatic decline in revenues and earnings after 2013. My investment checklist (as it was in 2018) included the question: Does the company operate in markets where demand is expected to grow?

I answered yes, and said that in aggregate I thought Xaar’s end markets would grow over the next ten years.

I still think that’s right. But what I didn’t think deeply enough about was whether Xaar was likely to hold onto its share of those markets. With hindsight, what I should have done (which I’ll do in a moment) is look at Xaar’s underlying markets to see how it had performed in each one over the previous ten or fifteen years. That would have given me a better insight into Xaar’s ability to retain market share captured during a market’s initial transition to digital printing.

As a general rule though, and somewhat obviously, defensive investors should be wary of companies where revenues and earnings are obviously very cyclical. I was, but I wasn’t wary enough.

Red flag 3: Product and market concentration risk

For several years, most of Xaar’s revenues were generated by a single product (the Xaar 1001) sold into a single market (ceramic tile printing). This was an obvious example of concentration risk. I thought Xaar’s patents would protect it from competing products, somewhat reducing the risk of obsolescence, but that wasn’t the case.

Once purchased, a Xaar printhead might last five or ten years. That gives competitors a lot of time to develop better and/or cheaper printheads which don’t infringe Xaar’s patents. As a result, Xaar’s printheads were often replaced with alternatives as they became available.

Red flag 4: No significant durable competitive advantages driving consistent, sustainable growth

One of the most important changes to my investment checklist is that it now begins with a clear question: Has the company demonstrated consistent earnings power?

In other words, has the company produced revenues and earnings which have trended upwards, reasonably steadily, for many years? Xaar clearly fails at that first hurdle. Its earnings per share went from virtually zero in 2009 to more than 40p in 2013 and then back down to about 10p in 2017. That is not what I’d call consistent earnings power and its revenues have been almost as volatile.

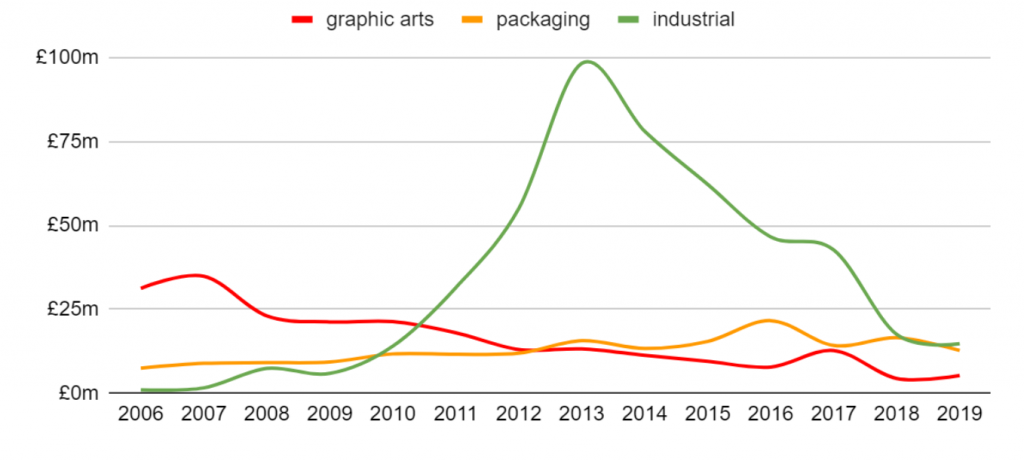

While Xaar’s volatile results are not ideal for a defensive value portfolio, the real problem is what they say about the company’s competitive strengths and its ability to retain market share over time. To show you what I mean, we need to look under the covers by separating out Xaar’s revenues by primary end market. These are: graphic arts, packaging and industrial.

This chart gives a much clearer view of what went on inside Xaar over the last 13 years.

Xaar’s results are dominated by a one-off boom and bust in industrial printing

Graphic arts: This was Xaar’s first major market, growing rapidly to peak revenues of £35m in 2007. That growth was followed by a long decline to almost zero revenues in 2019 as Xaar struggled to maintain its share of a maturing market.

Industrial: Xaar’s sales into this market were dominated by the ceramic tile market, which followed the same pattern as graphic arts but on a much larger scale. There is an explosion of revenues from £6m in 2009 to £98m in 2013, than a collapse back to £18m as Xaar was unable to maintain sales once the initial transition to digital printing came to an end.

Packaging: This was the only core market which produced fairly steady revenue growth for Xaar, going from around £8m in 2006 to £17m in 2019.

In summary, then:

- Xaar is a company that has repeatedly shown that it can pioneer the advance of inkjet printing into new markets.

- It has also repeatedly shown that it has trouble maintaining sales and market share once the transition to digital printing has taken place.

The fact that Xaar has failed to retain market share strongly suggests that it does not have durable competitive advantages beyond its ability to crack open new markets.

And as its track record shows, that is not enough to produce consistent, sustainable growth of revenues, earnings and dividends over the long-term. On that basis, I no longer think Xaar is a suitable holding for a defensive value portfolio.

3) Should Xaar be sold immediately?

I had the option of selling Xaar in November 2019, as soon as the initial post-disaster autopsy was complete. But I didn’t.

There were two reasons:

- I thought Xaar was attractively priced at its then-price of 48p and

- I wanted to see if the new CEO’s review would come to the same conclusion as mine.

Let’s talk about price first.

Although Xaar isn’t the right sort of company for a defensive value portfolio, I also don’t think it’s worthless. When I reanalysed Xaar in November, its share price was 48p. That’s 48p for a company which, even if we completely exclude the ceramic tile market, had repeatedly produced revenues of more than 60p per share.

With historic margins of more than 10% I thought Xaar, once stabilised, should be able to generate earnings of 6p at the very least, and perhaps a dividend of 3p given its usual dividend cover of two-times. And with a share price of 48p in November, that gave Xaar a very conservative potential dividend yield estimate of 6.25%.

On that basis I thought Xaar was likely to be very cheap at 48p. So I decided to hold on and wait for a better price and also to see what the new CEO would say.

Selling Xaar now because its turnaround plan is in place and the price is less obviously cheap

In April I found out what the new CEO had to say as he announced Xaar’s new turnaround plan. One critical element of that plan was the decision to stop selling Xaar printheads direct to end users (the companies that buy and use printers) and instead only sell to printer manufacturers.

The practice of selling direct to end users was seriously undermining the business model of printer manufacturers. They like to have a monopoly on the supply of printheads for their printers, which means their customers have to buy replacement printheads from them, with a nice profit built into the price.

Another key part of the turnaround plan was to start investing more heavily in developing Xaar’s existing products, instead of pumping huge sums into revolutionary products like Thin Film. In time that should make the company more competitive in both new and mature markets. It should also help the company build a reputation for investing in and developing its core products, making it a more attractive partner to printer manufacturers.

Overall, the turnaround plan seems sensible enough and it matches up with my assessment that Xaar’s core products are not competitive enough in mature markets.

So why am I selling now? The answer is that Xaar still doesn’t have a long track record of consistently high profitability driving repeatable and sustainable growth thanks to market leadership and durable competitive advantages. So it still isn’t suitable for a defensive value portfolio.

The only reason Xaar stayed in my portfolio after November was its share price, which seemed to be extremely low at just 48p. However, at the beginning of September, Xaar’s share price reached 90p, which is about 90% higher than it was in November. At 90p my conservative estimated potential yield, based on a 3p dividend being paid at some point, is just 3.3%. That isn’t bad, but it doesn’t represent a sufficiently attractive income for such a volatile and uncertain business. And that’s why I sold Xaar at the beginning of September.

It is of course disappointing to record a capital loss, but owning Xaar has definitely made me refocus my efforts on the fundamentals of defensive value investing:

- Broad diversification – Investing in at least 30 companies operating in a diverse array of countries and industries.

- Quality companies – Buying market-leading companies with robust balance sheets and durable competitive advantages, which leads to high levels of profitability and repeatable, sustainable growth.

- Value prices – Owning those companies when their dividend yields are high and their valuation ratios low relative to similarly successful businesses and/or the market average.

This article was originally published by UK Value Investor.