As coronavirus (covid-19) is reshaping the real estate landscape, property professionals need to rethink their approach to extreme risk events. It is now evident that mainstream risk management techniques are insufficient to deal with irregular large-scale unpredictable events like pandemics. These black swan extreme events are susceptible to wild randomness and can form substantial performance data fluctuations as evident in fat tailed probability distributions. With uncertainty, a better approach in parallel to probability analysis, is the application of extreme downside risk management.

The first step is to peel back the elements and explain the types of natural and man-made events, and how a framework can be constructed around the categories. Natural disasters are catastrophic events resulting from natural forces which are unplanned and socially disruptive events with sudden and severe disruptive effect. This is often termed as ‘Acts of God’ where there is no human control – Hurricane Katrina, Ebola outbreak and Nepal earthquake.

Whereas man-made disasters are those catastrophic events that result from human decisions. These can be sudden or over a longer time period and include social-technical disasters which is due to accumulated unnoticed facts generated from the interaction between internal and external factors – Chernobyl, Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) Fund collapse, global financial crisis.

In recording the number and magnitude of extreme risk events, Swiss Re (2020) database shows a concerning trend in the number of recorded events, increasing from 105 to 315 in the past 40 years. Most evident is the increased irregularities of major disasters causing significant casualties and economic loss alongside the upswing in natural catastrophes (202 in 2019) fuelled in part by emerging climate change challenges.

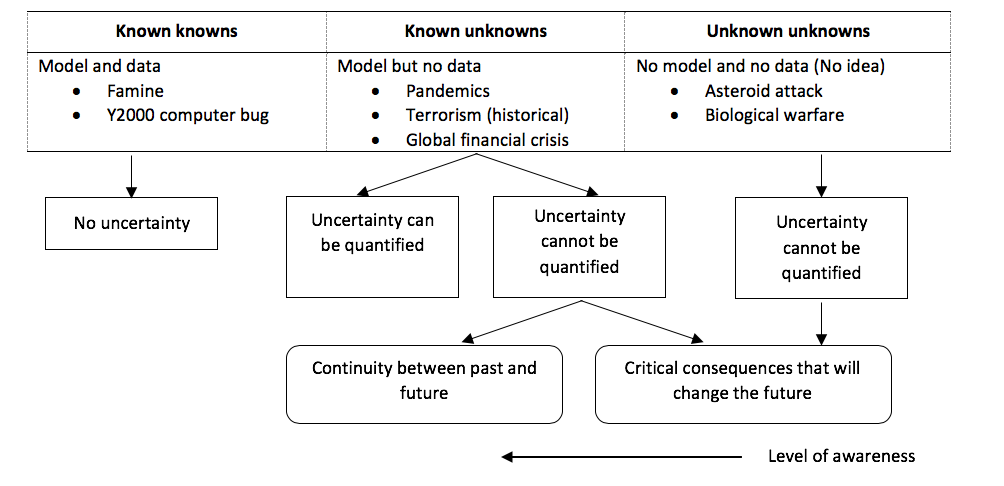

With large-scale disasters increasingly dominating the global environment, Diebold et al (2010) skilfully conceptualised the downside risks into Known (K), the unknown (u) and the Unknowable (U) risk classifications based loosely around the famous adage from the former U.S. Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld in 2002. These categories can be used to construct a framework to a better understanding of uncertainty surrounding extreme unpredictable events – see Figure 1

Figure 1

Categories of extreme risk: Distinguishing the known and unknown events

Figure 1 provides three categories: known knowns (K), known unknowns (u) and the unknown unknowns (U), where the ‘K’ event is known what could happen and when, for example: the Year 2000 computer bug. These events can be measured and the disruption (worst case) forecasted. For ‘u’ events, these may be quantifiable but the time of occurrence remains unknown, for example: earthquakes, pandemics. The ‘U’ event is difficult, if not impossible, to model. It is hard to imagine what kind of events might fit into this category, for example: asteroids colliding with earth, alien invasion etc.

The real estate challenge is focused on the known unknown events which can be twofold, i) locational risk (earthquakes, hurricanes) which can damage the physical building and ii) economic loss for the space occupier, as operational risk (for example, global financial crisis, cyber-attacks) may spread across several unrelated locations at different timelines. Critically, advances in digital technology has led to increased connectivity, making secondary ’space’ impact significantly more important after a major known unknown event.

Working out the implications of an extreme risk event, like covid-19 depends on how uncertainty can be quantified and managed. Resilience and flexibility will decide the future between continuing with past practices and embracing change to create new modes of operation across social and economic markets. With this will come exciting real estate opportunities to reshape society in a more forward looking global environment.

In summary, extreme risk events appear to be a blind spot in the property decision making process. Moving forward, there is a need to identify these type of events and place them into known / unknown categories. In understanding the implications, strategic management can be planned for and managed in offering a systematic guide to the real estate decision making under uncertainty.

Contact: David Higgins david.higgins@bcu.ac.uk

Treshani Perera treshani.perera@rmit.edu.au

Further reading

Higgins D and Perera T, 2018, Advancing Real Estate Decisions Making: Understanding Known, Unknown and unknowable Risks, International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, Vol 36, Iss 4, pp.373-384.

Higgins D and Perera T, 2016, Corporate Real Estate Black Swan Strategy: Beyond Probability and Resilience, Corporate Real Estate Journal, Vol.5, p 226 – 247