It really doesn’t get much better than this, folks.

Last July, I wrote a post called “If this is a bad economy, please tell me what a good economy would look like”. At that time, there was still quite a lot of debate about whether the U.S. economy was doing well. As of October 2024, “the economy is good” is much less of a bold thesis. Even Fox News, which is generally loath to say anything good about the economy just before an election when a Democrat is in the White House, is being forced to admit that yes, things are going well.

Essentially, there are four things you want from a macroeconomy:

- You want high employment rates, so that everyone who wants a job has a job.

- You want low and stable inflation rates, so that people know how much a dollar will be worth a month from now.

- You want fast wage growth, so that regular working people are taking home their share of economic growth.

- And you want fast productivity growth, because ultimately that’s what creates durable gains in living standards.

Right now, the U.S. economy is giving us all of those things.

Pretty much everyone who wants a job has a job

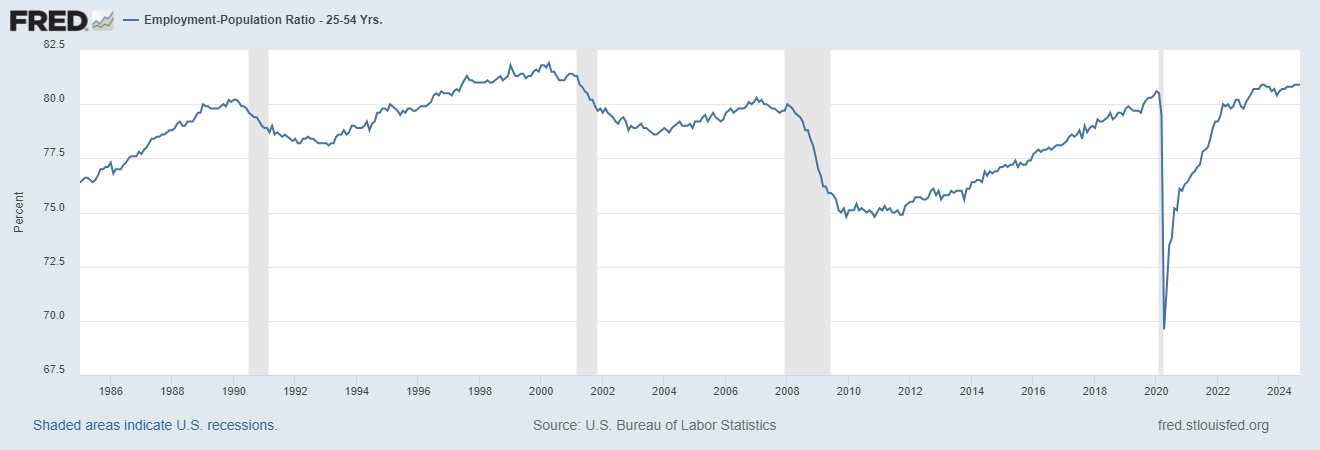

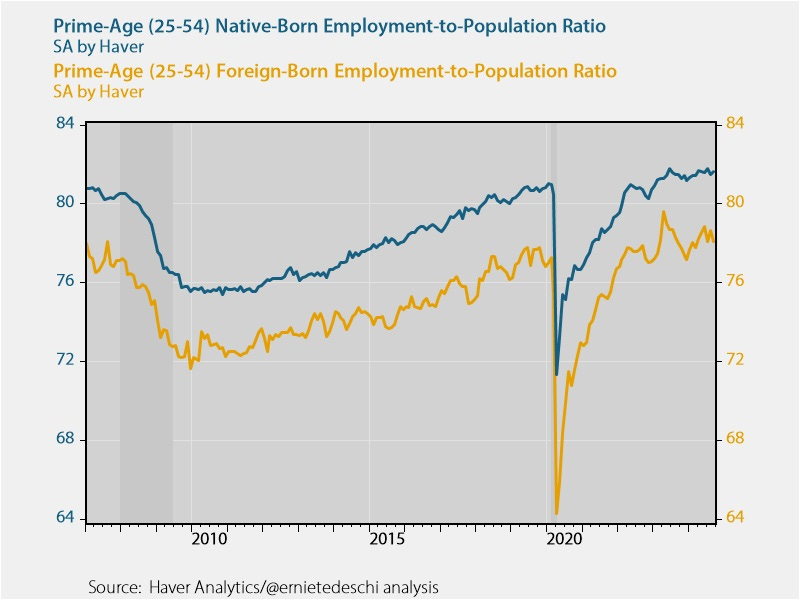

Let’s take a look at the labor market. I like to look at employment rates for people age 25-54, since these people are unlikely to still be in college or to take early retirement. This rate is holding at 80.9%, which is higher than before the pandemic, and in fact is the second-highest rate in U.S. history (the highest being 81.9% in 2000):

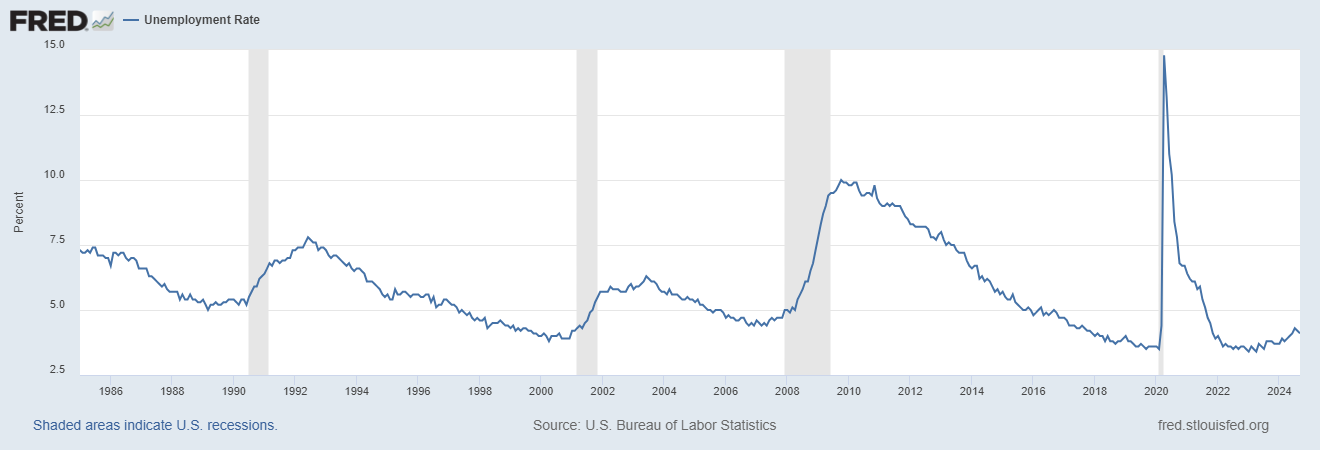

The unemployment rate isn’t quite as reliable of a statistic (since it depends on who says that they’re currently looking for a job). But for what it’s worth, it’s very low, at 4.1% — a little higher than in 2023, but still very low in a historical sense:

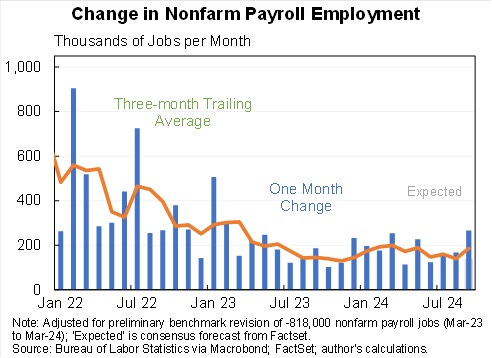

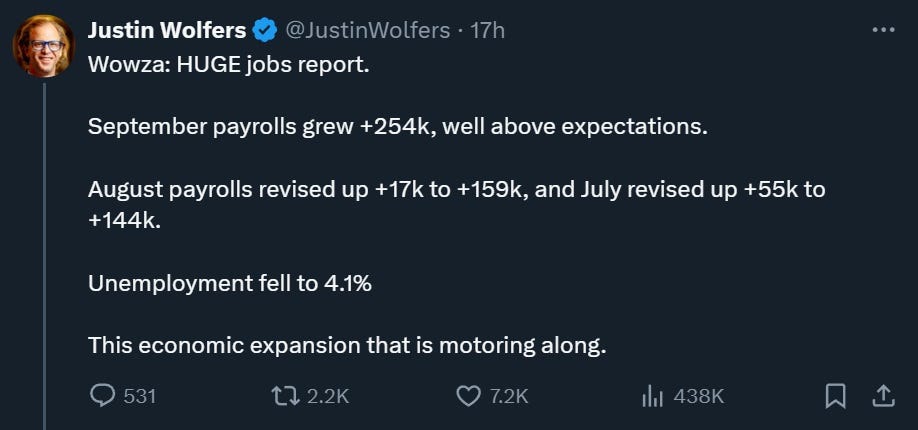

The last month of job growth was particularly strong, sending the unemployment rate slightly lower. When an economy is near full employment, it gets a lot harder to keep adding jobs at a steady clip, and yet somehow the American economy keeps doing it:

In fact, it gets even better. This month saw upward revisions to job growth for July and August, two months that had looked a little more tepid. In fact, the U.S. added more jobs during those months than we initially thought:

So the labor market just looks incredibly strong right now.

Of course, it being an election year, there are a few people claiming that the data is unreliable, or that there are reasons why the labor market numbers aren’t as good as they seem. So let’s answer a few of those questions.

“Won’t these jobs numbers just get revised down?”

Well, we don’t know if the September jobs numbers will get revised downward when the final data come in. But we do know that the July and August numbers got revised upward. So there’s a chance the September numbers will be revised up as well.

Marco Rubio did falsely claim that 16 of the last 17 monthly jobs numbers were revised downward. There was a string of mostly negative revisions in 2023 and early 2024 — though as you can see on the chart above, which includes those revisions, the final numbers were still really good. But that string has ended lately — July and August 2024 got revised upward, as did March 2024. (There were also upward revisions in July 2023 and December 2023, which just makes Rubio’s factoid even more wrong.)

“Isn’t it just foreigners getting jobs, not native-born Americans?”

Nope. The Baby Boomers are retiring, so the total number of native-born American workers is going down. But the employment rate of native-born workers is especially high right now — higher than in 2019. In fact, the gap between the native-born and the foreign-born has even widened a little bit:

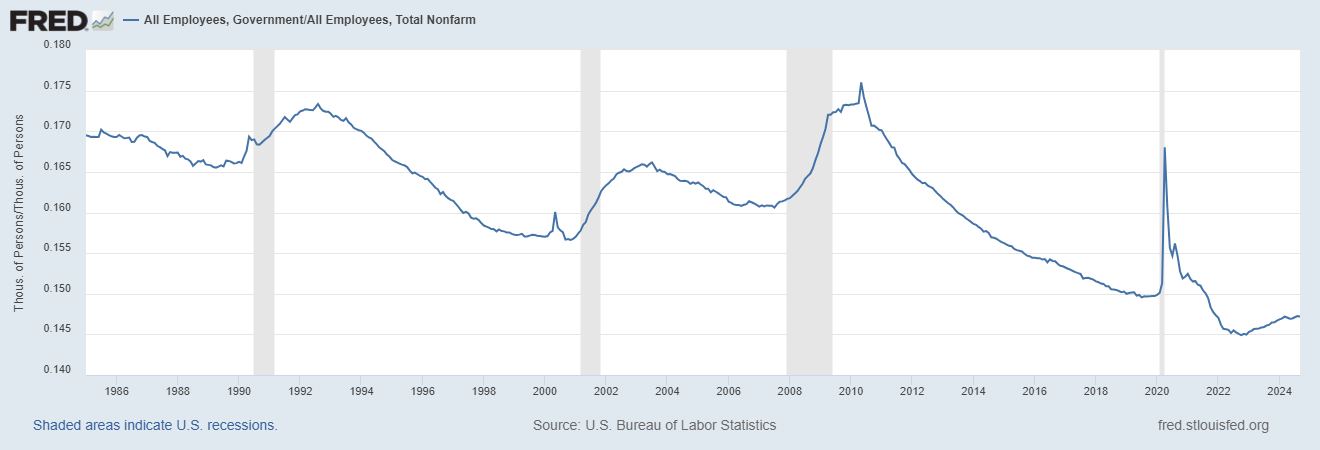

“Aren’t these just government jobs?”

Nope. Government jobs are a smaller percentage of overall U.S. employment than they were in 2019, continuing a decades-long downward trend:

So yes, the job market in the U.S. is very good. If anything, it’s even a little improved from last month.

Inflation is back to normal

Now let’s look at prices.

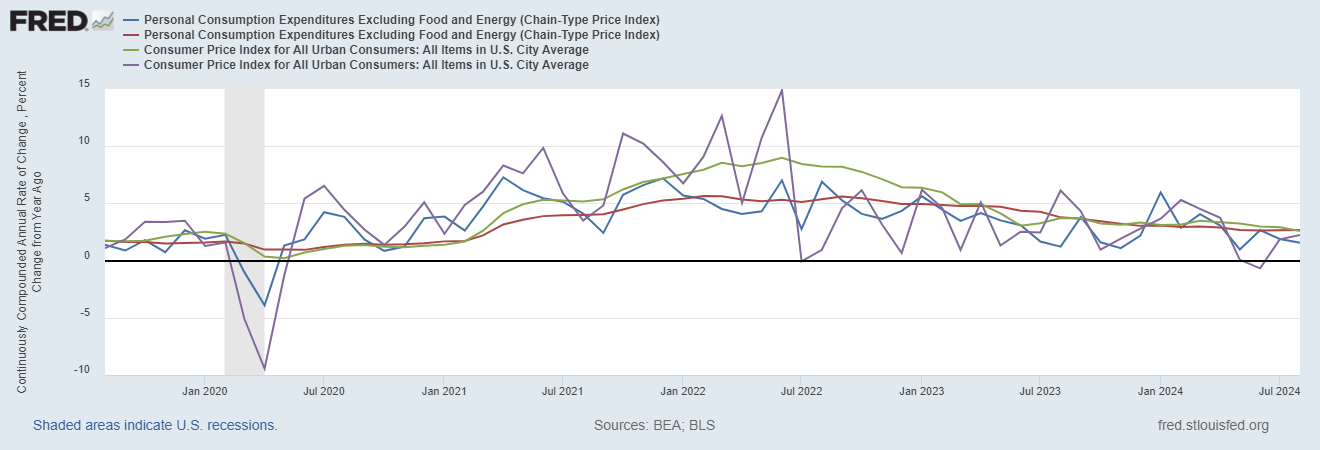

Remember, there are two price indices we usually look at for inflation: the PCE, which counts health care more, and the CPI, which counts rent more. We can look at headline inflation, or we can look at core inflation, which doesn’t include food or energy. And there are two basic time periods over which we typically measure inflation — the annualized month-to-month change in prices, or the one-year change in prices. But no matter which of these you look at, the story is the same — inflation is back down to its target range. For example, here are core PCE inflation and headline CPI inflation, both measured month-to-month and yearly:

You’ll notice that the month-to-month numbers are lower than the yearly numbers, meaning that inflation is still decelerating.

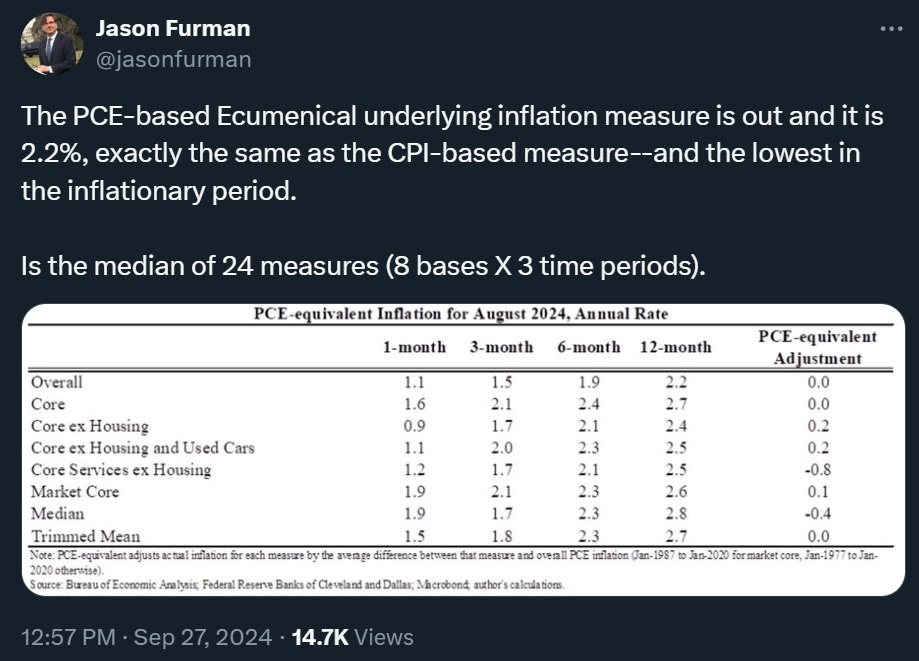

In fact, there are a bunch of other inflation measures, and they all say the same exact thing:

The post-pandemic inflation has been conquered. Inflation could come back, of course, and we have to be vigilant. But for right now, the problem is gone.

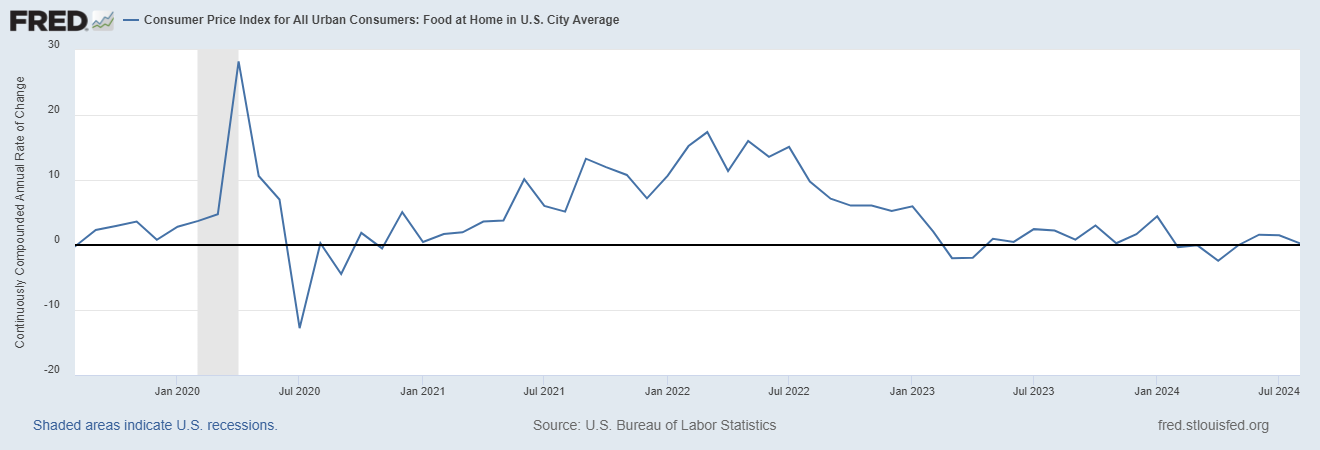

Meanwhile, most of the household necessities that got more expensive during the post-pandemic inflation are no longer getting more expensive. Gasoline prices are down to below where they were a decade ago. And grocery prices stopped rising almost two years ago:

In fact, grocery prices are expected to fall over the next two years.

Wages and productivity are both up

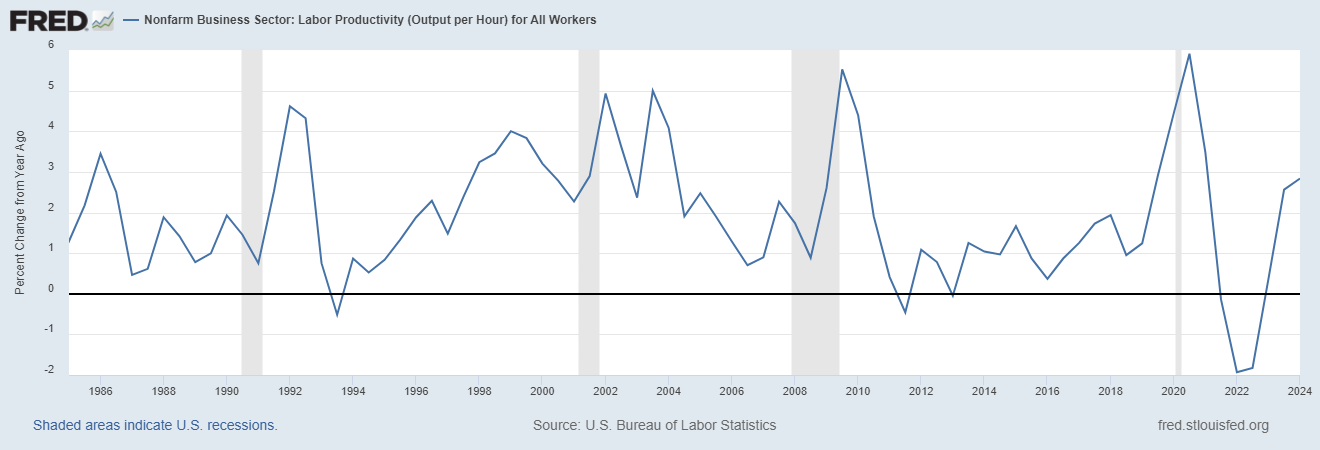

Labor productivity growth is solid — it has returned to a historically average level, and is actually higher than it was throughout the 2010s:

This isn’t yet the “roaring 20s” we’ve been hoping for, but it’s looking pretty darn good. Excluding recessions — which cause productivity to jump because lower-earning workers get laid off — it’s the best we’ve done since the early 2000s.

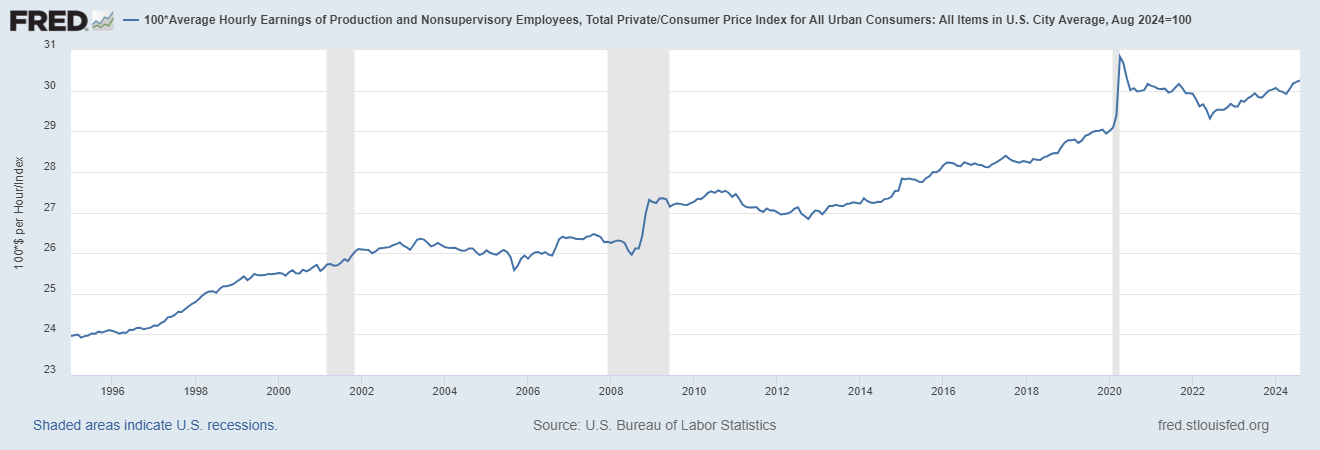

Wages are growing too. Real average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers — a good proxy for the median worker’s wages — are back on their pre-pandemic growth trend:

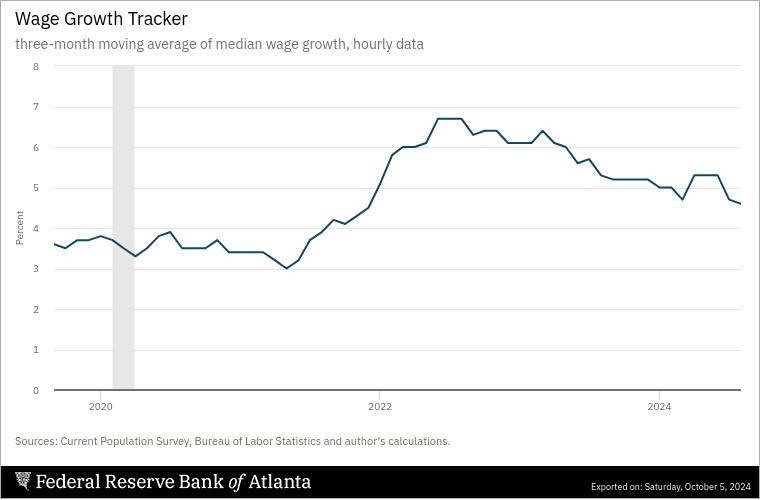

And here’s the data from the Atlanta Wage Tracker, which tries to hold the composition of jobs constant:

These are nominal wages, so we have to subtract inflation to get real wage growth. Inflation is currently around 2%, compared to about 4.5% wage growth, so real wages are rising.

In fact, for workers at the bottom of the distribution, the gains have been even larger. Wage inequality is falling, even as wages rise.

How about wealth?

You’ll note that I didn’t include wealth on my list of things we want from a macroeconomy, because this is actually something people disagree on. When wealth for the rich increases, some progressives complain. And since middle-class wealth is mostly in owner-occupied housing, when middle-class wealth increases, it makes houses less affordable for people who don’t yet own them. So not everyone agrees that more wealth is good, either for the rich or the middle class.

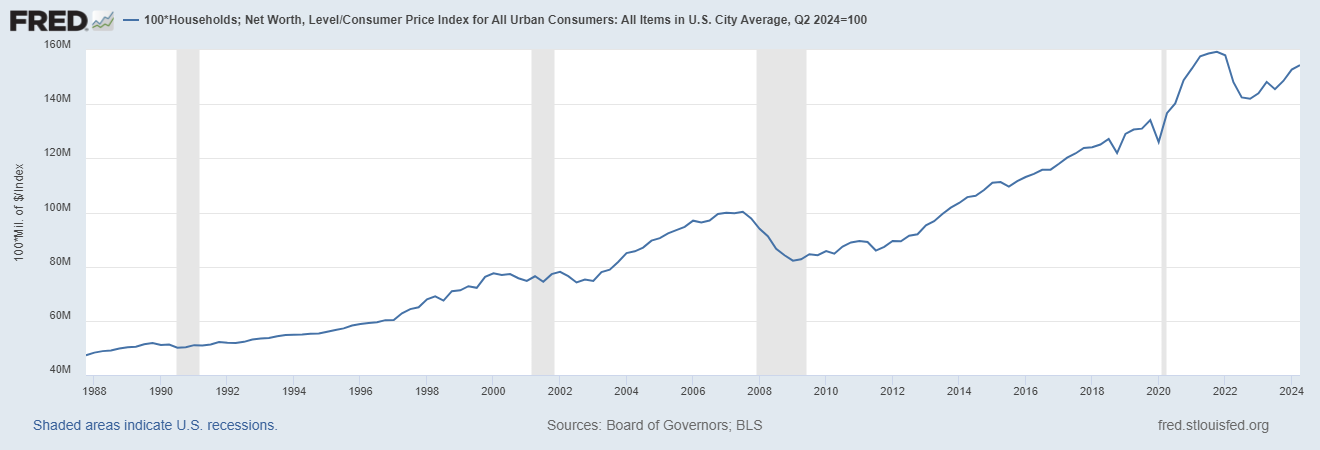

That having been said, the U.S. economy is certainly generating a lot of wealth. Household net worth, adjusted for inflation, is at or above its pre-pandemic growth trend:

The stock market is doing remarkably well, despite some apocalyptic predictions from certain quarters:

(This number isn’t inflation-adjusted, but the returns are so large that inflation doesn’t change much.)

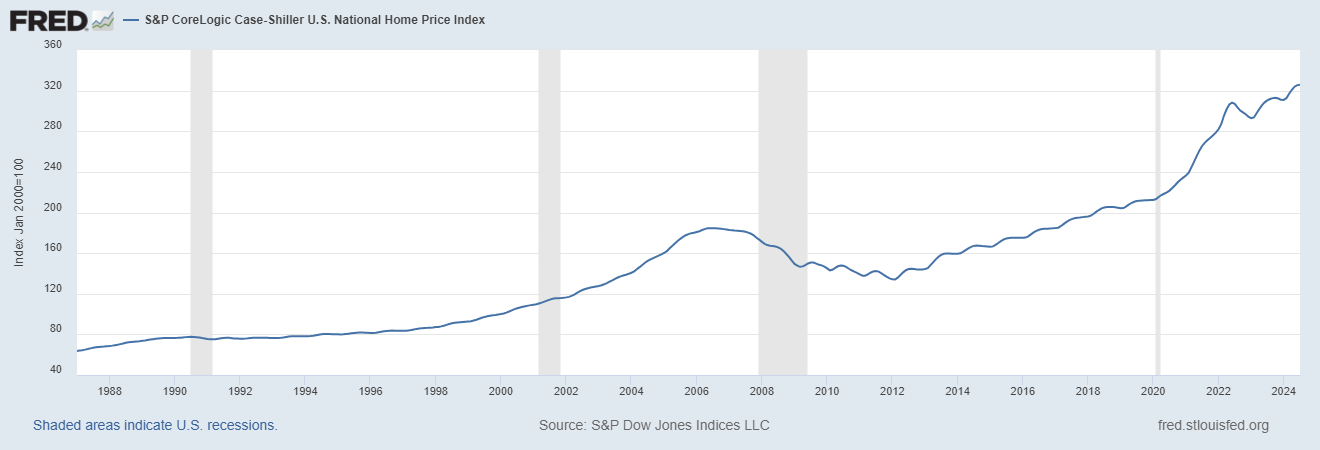

House prices, which are a good proxy for middle-class wealth, are also up:

Like I said, not everyone is happy when stock and housing prices go up. But wealth is being created in America at a rapid pace.

America is beating the world

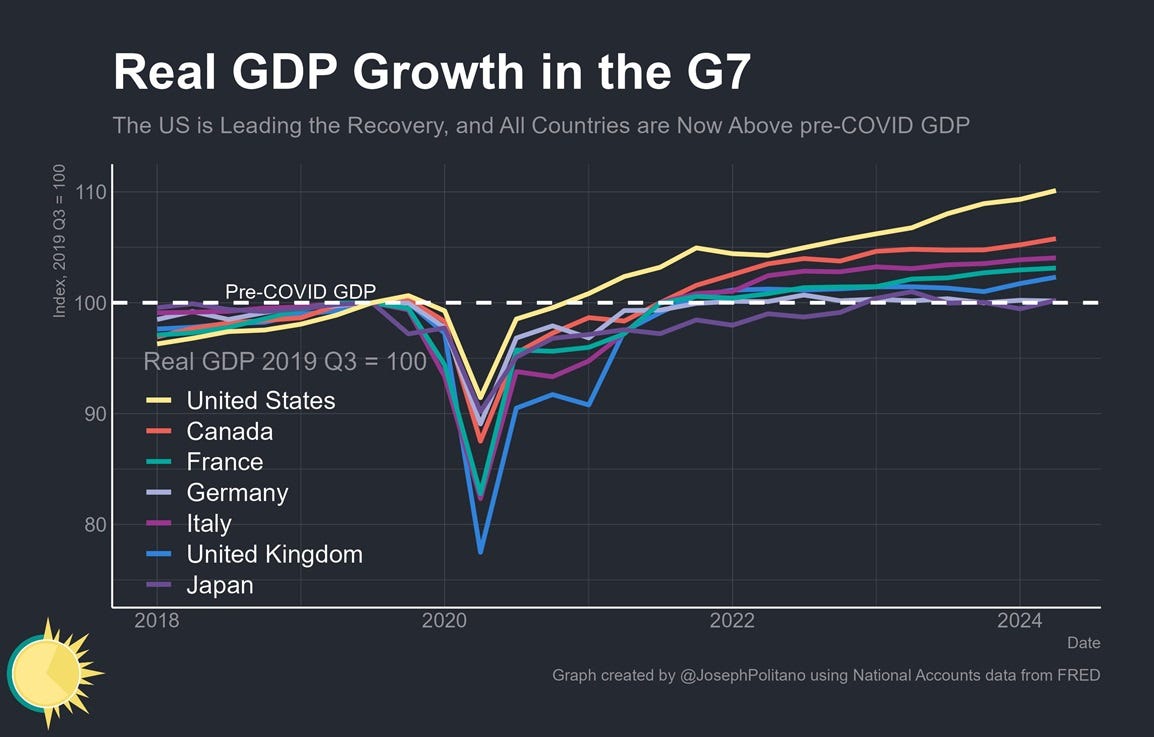

It’s also remarkable how much better the U.S. is doing than other advanced countries. I didn’t list “GDP growth” as one of the things we want from a macroeconomy, but it’s an easy metric to compare across countries. And here, the U.S. has been pulling away from the pack:

In fact, though good data on Chinese growth is hard to get, independent estimates suggest that China’s growth is now a bit lower than America’s as well — at least, until they recover from their real estate bust.

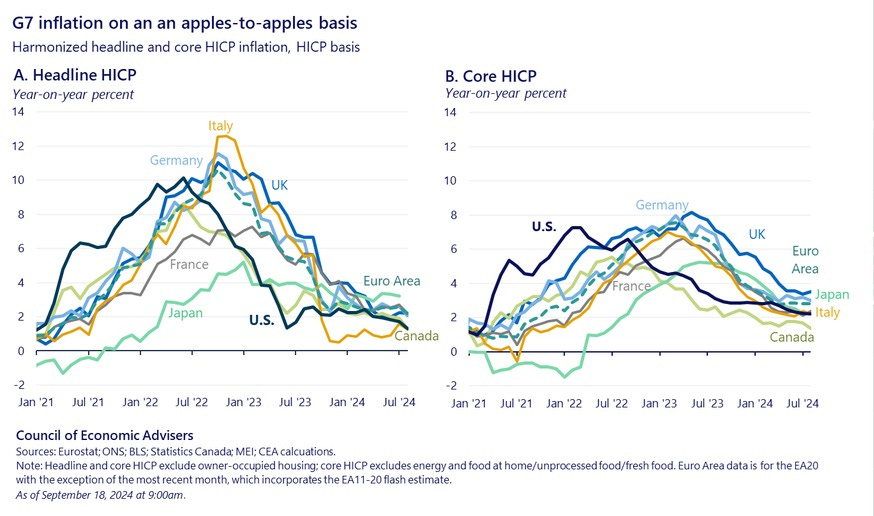

Meanwhile, U.S. inflation was a little higher than other rich countries back in 2021 (probably because we spent a lot more money on pandemic relief), but now it’s lower than almost anyone else:

Of course, it doesn’t give me any pleasure to see America’s allies growing slowly and suffering from inflation. But it is remarkable how the U.S. is managing to have both faster growth and lower inflation than other countries at the same time.

To sum up, America’s economic performance is amazing. It’s doing better than any rich country could expect to be doing.

So what’s the catch?

A lot of people are wondering: How much credit should we give Biden for this stellar economy? I usually try to avoid this question — the fact is, the President inevitably does get a lot of credit or blame for the economic situation, even when he doesn’t deserve it, and nothing I say will change that.

That having been said, I do think Biden gets some of the credit here. He reappointed Powell to the Fed — Powell’s interest rate hikes helped to quell inflation, without increasing unemployment by much. We still don’t know how that happened, and it represents a stroke of luck. But Biden’s reappointment of Powell does seem to have been a very good move, at least with the benefit of hindsight. Biden also allowed a ton of oil drilling, making the U.S. an energy superpower, which I’m sure helped. And Biden’s industrial policies have spurred private companies to build a ton of factories, which also provided a modest boost to national growth.

These are all things that will have long-term benefits as well as short-term ones, and so I’m happy about all of them.

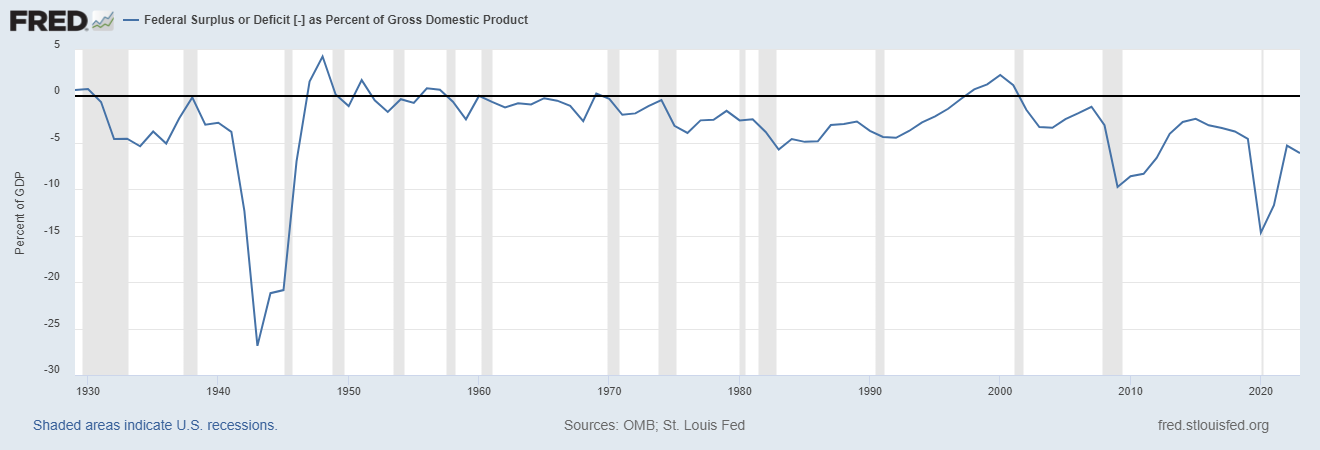

But there’s one more thing Biden has done to boost the economy, and this is the one that worries me. Even after the end of pandemic relief spending, the U.S. government has been running huge deficits, unprecedented outside of war or severe recession:

In 2024 the deficit is projected to be $1.9 trillion, which in a $29 trillion economy is about 6.5% of GDP — even bigger than in 2023.

Deficits do probably boost growth. But you’re not supposed to do this in good economic times — you’re supposed to do austerity in the boom, and fiscal stimulus in the bust. If you keep running emergency-level deficits during every boom, it’s unsustainable, and eventually there will be a reckoning.

I’m not sure how much the U.S. economy’s amazing outperformance is due to outsized deficits. Most of the extra cost since 2022 has been due to higher interest rates, which the Fed raised in order to combat inflation. That tends to reduce the effect of deficits on GDP, because it’s just paying bondholders back instead of stimulating the economy.

But it would have been fiscally prudent to cut other spending and raise taxes in response to those increased interest costs. That austerity would have slowed the economy a bit. Therefore the fact that we chose not to do austerity in 2022-24 is responsible for some modest percentage of the U.S.’ hot labor market and world-beating GDP growth.

It’s probably too much to ask any President to do austerity in an election year. And of course, Trump will raise deficits by much more if he gets elected (remember that he also increased deficits in an economic boom, in his first term; this time, he has less to lose). But I do think that the day of reckoning for the federal debt and deficit is fast approaching; the window where big deficits can be used to supercharge the economy is about to close.

But that is, necessarily, something we’ll worry about later. For now, let’s just take a moment to appreciate how amazing the U.S. economy is doing on all fronts. Times this good don’t come along very often.

Update: I’m very far from the only person saying this. Mark Zandi, the chief economist of Moody’s Analytics, sums it up well:

This article was originally published in Noahpinion and is republished here with permission.