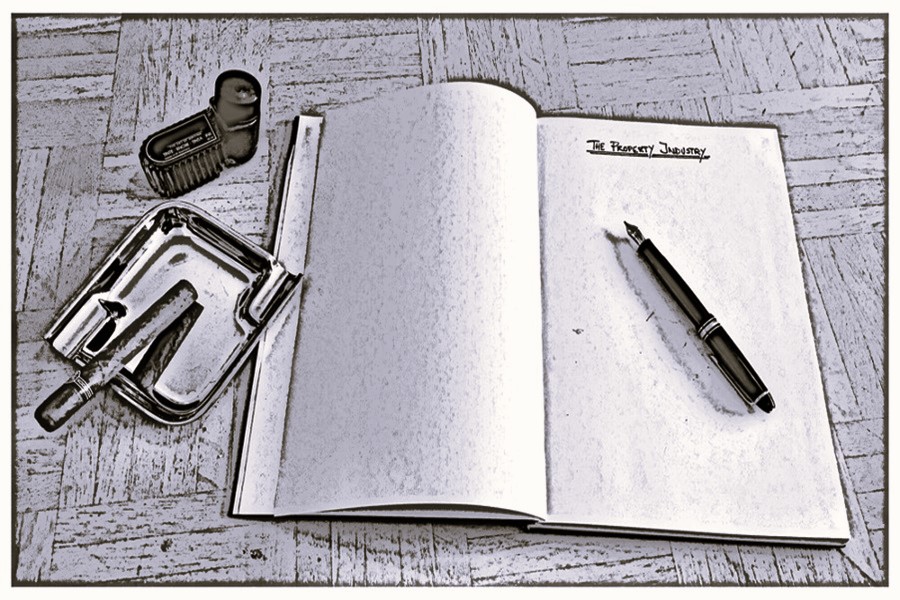

The clean page optimism of a New Year in France.

In the unwritten codes of French social behaviour, the giving and receiving of les voeux is much more meaningful than the cursory “Happy New Year” (or even HNY) of English culture. Instead, wishing people health, wealth and happiness here can sometimes feel more like a solemn vow (the direct translation of the word voeux). Failing to acknowledge the first meeting of a New Year – and delivering sincere voeux – is a serious breach of the behavioural code. International surveys have consistently recorded that French people are world-class pessimists and are proud of it. Cynics say that if January is for formulating and presenting meilleurs voeux, then the other eleven months are for not realising them. Nevertheless, the rejuvenating spirit of les voeux feels, briefly, like a welcome clean page, optimistic and pure.

Across Europe, the timings of marking the turn of a year are a moving feast; The British often start festivities in late October and are quite done celebrating by December 31. Some German states declare a January 6 public holiday for Epiphany and many Germans do not return from Christmas break before then. Ukraine, seeking to synchronise with the EU, has just officially reinstated December 25 as Christmas Day instead of January 7 – the date in the Orthodox Christian calendar. In secular France, religion is low profile as the 1958 constitution of the Fifth Republic enshrined laïcité (secularism) as a key principle of being a French citizen. Today, France is home to the largest Muslim and Jewish populations in Europe and the festival of Christ feels distinctly less religion-centric than in, say, the UK. However, if December in France seems less intense than in the UK, January feels more meaningful. Throughout January in France, presenting les voeux is a key ritual in personal and professional life.

At a personal level, wishing strangers good things for the coming year is expected behaviour at the vet, the petrol station, and the boulangerie. New Year cartes de voeux are important and until recently, over 20 million cards were sold here each year – mostly to be sent in the post with stamps. Decorum suggests they be written in real ink with well-chosen content such as three tailor-made adjectives for each recipient. The disruptors of this old-style behaviour – social media channels, SMS, and WhatsApp – are making for less activity at La Poste and – sadly – more formulaic and less heartfelt greetings. One charming personal ritual that still thrives is the family ceremony of La Galette des Rois. Consuming the marzipan-flavoured “King Cake” is linked to Epiphany although boulangeries sell galettes well beyond January 6 and the arrival of gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

Generous year-end gifts are also fast disappearing in French working life, with givers and takers of business presents increasingly sensitive to compliance and perceptions of bribery. The case of vintage Krug champagne from a grateful lawyer is now, seemingly, a relic of a previous era. Similarly, the year-end greeting card has largely vanished, a victim of digitalisation, awareness of the environment, and simple expedience. Many businesses no longer clutter inboxes with “festive” mass emails. For the moment, the more personal January carte de voeux is still (just) a thing in French business. Custom dictates both that cards can be sent until January 31 and that it is bad form not to reciprocate wishes. Voeux are also delivered in the spoken word, with management staging internal ceremonies to generate a warm sense of collectivité and to showcase last year’s achievements and this year’s ambitions to selected external partners.

One new January behaviour here is the recent arrival from the USA/UK of Dry January or le Défi de Janvier, with a third of French adults wanting to try it in 2024. In response, France’s powerful wine lobby points out that, unlike the Anglo-Saxons, French people rarely drink to excess and that there is no need to pause binge drinking in this culture of “consommer avec modération.”

January 2024 is my 29th New Year in France and the month has rarely failed to give me a positive sense of renewal and hope. According to recent IFOP surveys, however, only 25% of French citizens are “optimistic for the future” – the lowest level since I started living here in 1995. Against that dark background, I will savour the positive clean page spirit of January in wishing the reader bonne année et tous mes meilleurs voeux!