If the property boom-bust cycle has permanently come to an end, what will that mean for investors?

I have previously written about the impact of low interest rates and quantitative easing on the Japanese economy in the 1990s and 2000s and how that relates to today. Now, that is of course an interesting mental exercise and piece of history, but how does it relate to the world we find ourselves in today – and where we might end up tomorrow? What are the investment implications if we are now in a world where the real estate boom-bust cycle has been replaced by permanently cheap capital, no inflation, consistently low unemployment and therefore muted economic cycles?

There are some fundamental differences between the situation today and that of Japan throughout the 1990s–2010s, which I believe may result in different outcomes for real estate and markets overall. Firstly, when Japan was trying to implement super-low interest rates and quantitative easing, it was the only one doing it; the rest of the world continued as normal. Today, everyone is doing it: even Brazil has the lowest nominal rates in its history.

Secondly, Japan had been running very large export surpluses during its boom years and keeping its currency as low as possible, to the chagrin of other countries around the world. It was forced to revalue its currency in 1985 and cut rates; this in turn led to a credit bubble and speculative investment, with the Nikkei nearly trebling in value over three years before collapsing by 50% when the Bank of Japan began raising rates again. Today the countries in question are a mix of net exporters and importers, and currency depreciation has not been done in a co-ordinated way with a single focus point: countries have independently been trying to race each other to the bottom, and in doing so, no one relatively speaking has got there.

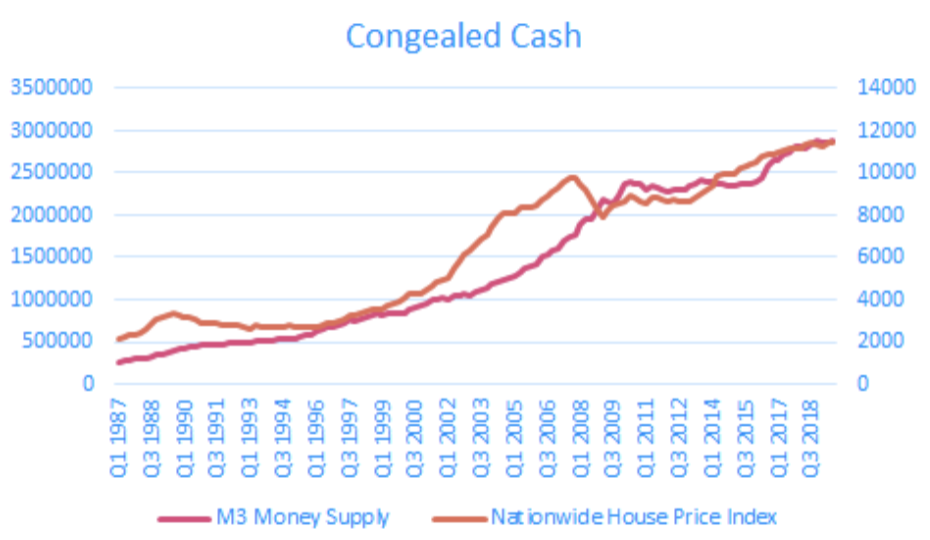

So, what may happen to real estate? As a former boss of mine said, “real estate is congealed cash”, and with that in mind, if there continues to be more cash being pumped into the financial system, cheap debt for those with good credit, low inflation, low personal income increases and low unemployment then the game shifts even more in favour of those who can afford to buy – and more cash will congeal in buildings, at least for as long as interest rates stay low. The chart below shows M3 money supply plotted against the Nationwide House Price Index to illustrate this point.

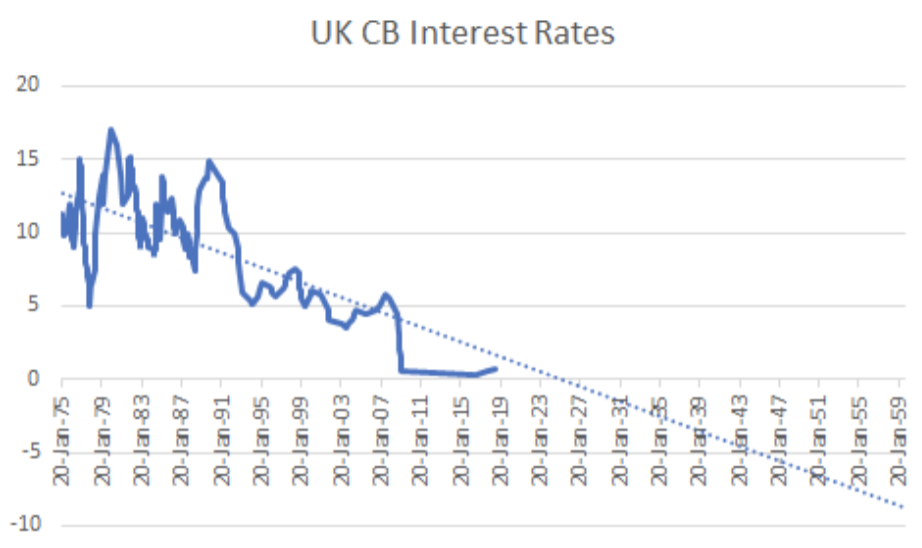

The trend in loose monetary policy does not seem likely to end soon, and the length of time that has passed will result in changes in individual expectations. What were called ‘low’ interest rates by anyone ten years ago are today accepted as pretty normal, and perhaps in another ten years they will be seen as completely normal. Five per cent interest in the future may be generally accepted as a high rate, much as we consider the double-digit interest rates of the early 1990s as ‘high’ by more recent standards. Not printing more cash may be considered hawkish. The chart opposite shows UK interest rates, with a very simplistic straight line put through them and extended out a few decades.

Provided that governments can maintain faith in their individual fiat currencies and there are no significant supply-side shocks, then there should not really be a reason for this situation to change: everyone has low rates and no one has any real reason to raise rates. Central banks will continue to target keeping inflation below a certain level, such as 2%, but over time the struggle will actually become keeping any inflation at all. In Denmark, now known for its negative rate mortgages, unemployment has been steadily declining and now sits at 5% while incomes have been gradually but consistently rising and house prices have increased by between 3% and 5% a year, but inflation is barely above zero.

This may be what the near future looks like: where the majority of supernormal returns have been had but prices and inflation keep on ticking upwards as long as governments keep printing money and keep rates low. In that kind of a world, real estate will likely become an ever more attractive investment, eking out above-normal investment returns, supported by governments, central banks and the general population.