Recent scholarship on investment patterns during the 18th and 19th centuries in Britain has uncovered the role of women as investors. By the late 19th century, rising real wealth and the promise of higher returns coupled with lower risk led both men and women from a widening social spectrum, including the less affluent, to own stocks and shares. Among these women was Marian Evans, known to her reading public as George Eliot, among a select but growing number of middle-class investors investing in colonial stocks during 1860-80. This is evident from Eliot’s diaries for 1879-80, which lists dividends from stocks in Australia, South Africa, India and Canada (Henry, N (2001). George Eliot and the Colonies. Victorian Literature and Culture, 29(2), 413-433).

All this was possible due to remarkable financial and institutional development during that time. Development of the banking system and provincial stock exchanges allowed British registered firms, firms incorporated overseas as well as UK and foreign governments to mobilise large amounts of capital from across Britain. Some scholars have pointed out that these investors were responsible not only for the expansion of industry at home but also for the march of capital abroad (Rutterford, J, Green, DR, Maltby, J, & Owens, A (2011). Who comprised the nation of shareholders? Gender and investment in Great Britain, c. 1870–1935. The Economic History Review, 64(1), 157-187). Interestingly, even before Britain’s dominance on global capital markets during the first era of globalisation (1880-1913), women were playing a key role towards the country’s global economic expansion. Taking the case of women investors in the Virginia Company during the early 17th century, Ewen (Ewen, M (2019). Women investors and the Virginia company in the early seventeenth century. The Historical Journal, 62(4), 853-874) argues that women determined the success of English overseas expansion not by ‘adventuring’, but by their purse. More importantly, women were not only investors during good times but during crisis as well. Using transfer records and ledger books of the Bank of England, Carlos and Neal (2004) examine women’s investment activity during the South Sea Bubble. They note that during 1720, women’s activity constituted 13% of the transactions measured by value, 10% of total sales and 8% of total purchases.

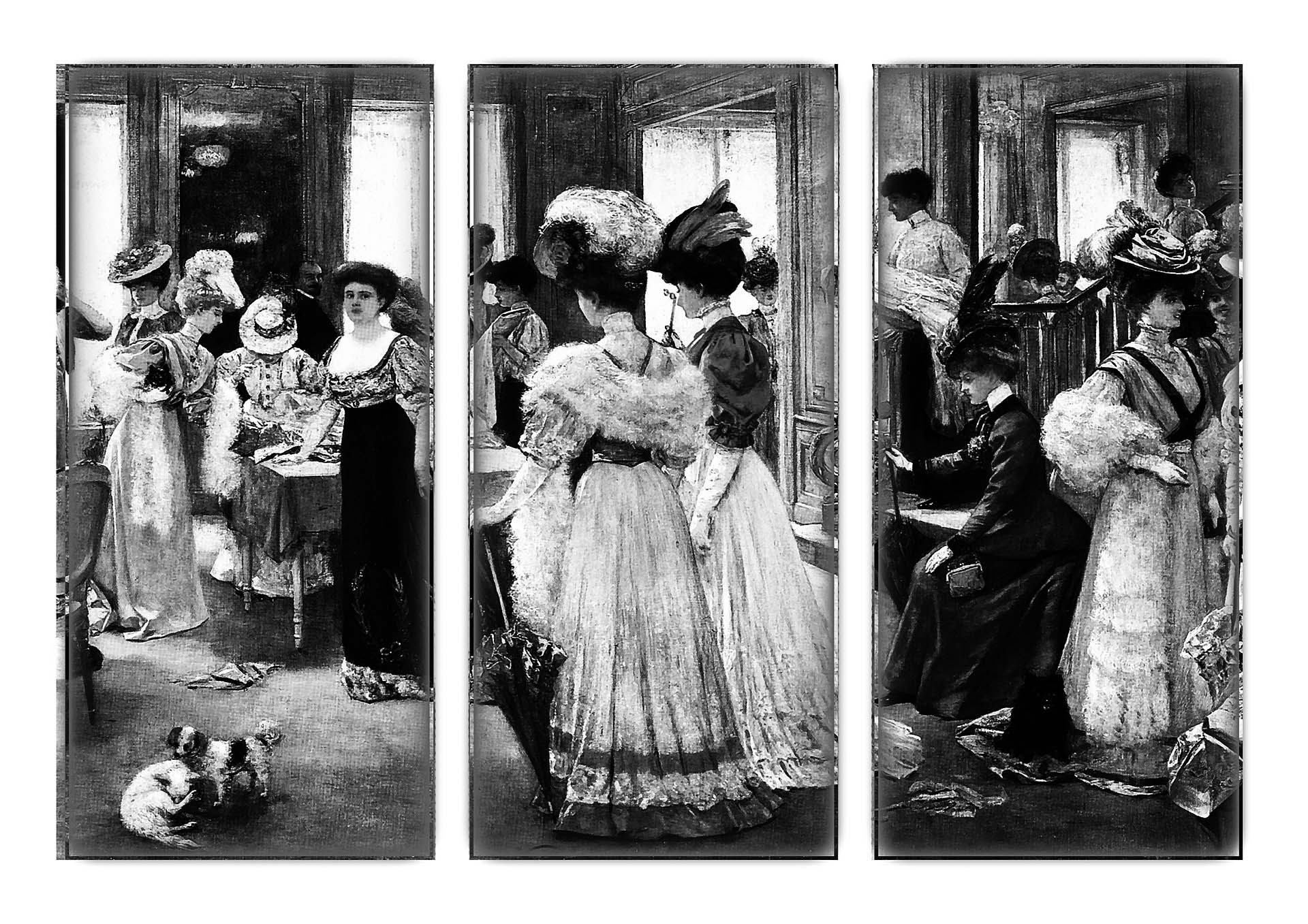

“Like their male counterparts, women investors also used the financial press as a source of investment information.”

During the late 19th century, women investors invested for different purposes; for income, capital growth, to supplement a low income or maintain a balanced portfolio (Laurence, A., Maltby, J., & Rutterford, J. (Eds.). (2008). Women and their money 1700-1950: essays on women and finance. Routledge). Although their choice of financial assets for investment appears to be varied, literature does point towards a general inclination for less risky assets, such as preference shares or debentures rather than ordinary shares. Like their male counterparts, women investors also used the financial press as a source of investment information, especially when they might be excluded from business networks. This point is extensively dealt with in the book Women and their Money 1700-1950, a collection of essays on leading experts in this field. Their research demonstrates that despite legal and social restrictions, women managed their own finances well. Moreover, they made themselves effective and engaged managers of the funds at their disposal. Women’s engagement in financial matters has been neglected in historical literature and there is much that can be learned about them as investors and their management of capital in the past.