China’s position on the world stage is changing rapidly as it moves to become a strategic competitor to incumbent economic powerhouses. Not least because of the recent trade conflict between the US and China and its long-term fallout as well as the covid-19 outbreak, it is imperative for companies to recalibrate their manufacturing relationships with the Chinese market.

While many manufacturers started to deploy a China +1 policy in the past, an approach involving further diversification (China +x) yields multiple opportunities and advantages.

This two-part mini-series will analyse various countries and regions around the world in terms of suitability to replace manufacturing capabilities currently maintained in China.

Significance of China’s manufacturing sector for global markets

China’s export-oriented manufacturing industries are mainly concentrated in labour-intensive and technology-driven industries. Accordingly, textiles/apparel (40% of global exports), as well as computers/electronics (28%) and electrical equipment (27%), are leading the pack in terms of manufacturing concentration.

However, labour costs in China’s manufacturing sector have seen a steady rise over the last two decades, which is driven by a number of factors:

- demographic impacts (such as the one-child policy);

- limited migration opportunity from rural areas to cities;

- regulatory impacts resulting in steady rises of minimum wages.

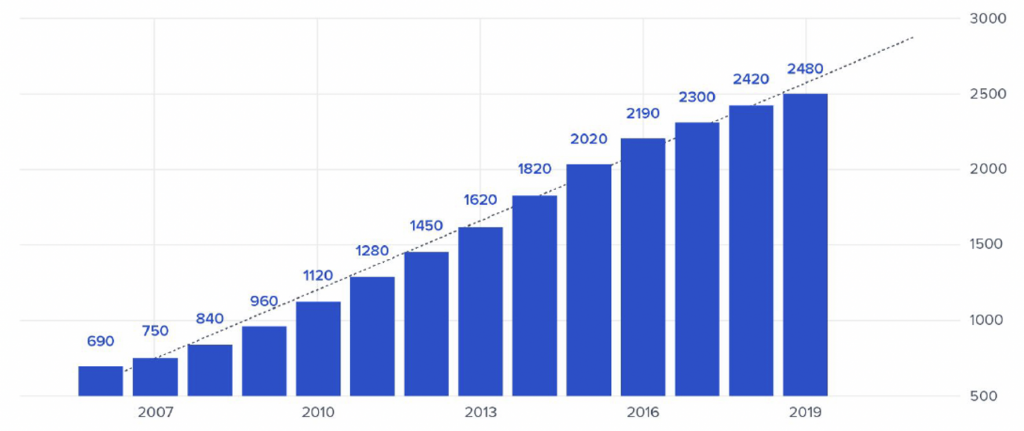

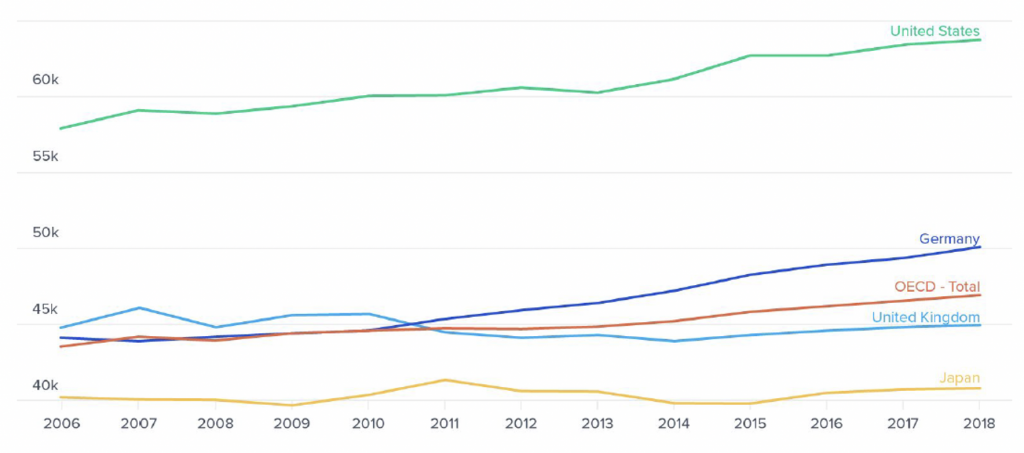

While the labour cost impact of the first two drivers is rather difficult to quantify, the rise in minimum wages is well documented. While still at a modest level, since 2006 minimum wages in China have nearly quadrupled while remaining almost flat in most OECD countries.

Minimum wage development in China, 2006-19 (Rmb)

Source: tradingeconomics.com; Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of China

Minimum wage development in major OECD markets, 2006-18 (US$)

While a number of manufacturing sectors in China have adapted by automating production, the impact on the competitiveness of China’s manufacturing sector is no longer negligible. More significant, however, is the already visible impact of China’s trade and non-trade relationship with its major trade partners. Additionally, the recent covid-19 outbreak and its disruptive impact on the supply chains of companies with production facilities in China has led to considerable soul-searching in a number of boardrooms to recalibrate global sourcing and supply chain strategies.

As a result, manufacturing locations beyond China will need to be evaluated in order to reduce the dependency on China-based outsourced manufacturing and/or China-based plants to supply global markets.

Since the availability of a qualified and low-cost workforce proved to be a major draw for China’s rise, alternative locations will be evaluated on that particular criterion. However, other parameters are of similar importance. Hence the discussion will also focus on political stability, the availability of utilities and transport infrastructure, financing, taxation and the regulatory framework as well as the freedom of capital flows.

Where next?

More than half of the world’s workforce is located in the Asia-Pacific region, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO), a UN agency. Another 14% are located in African countries, in particular Sub-Saharan Africa.

Regional shares of the global labour force, 2018

While there is certainly potential to ‘near-shore’ manufacturing capacities to western economies using automation as well as cost advantages due to trade corridors and lower transport costs, the focus of this analysis will be on labour substitution.

Manufacturing relocation opportunities

East Asia – major players, opportunities

The East Asia region makes up 27% of the global labour force, consisting of China, Hong Kong, North Korea, the Republic of (South) Korea, Macau, Mongolia and Taiwan. With relatively small and/or rather expensive workforces, Hong Kong, Macau, Mongolia and Taiwan do not really have potential for manufacturing shifts from China.

North Korea, with a workforce of 14 million people, would have the potential for a partial manufacturing relocation. However, apart from approximately 100,000 North Koreans working more or less openly in various international markets as part of government-sponsored labour export programs, the country is largely shut out from international manufacturing due to the UN and other sanctions imposed.

South Korea, on the other hand, with its 28 million-strong workforce, is well placed to capture a portion of the impending China replacement manufacturing capacity.

GDP per hour worked (US$) – South Korea vs major OECD economies

Unit labour cost percentage change – South Korea vs major OECD economies

Bottom line (East Asia)

With its highly qualified and efficient labour force, productivity and infrastructure, South Korea provides replacement opportunities to diversify some of the high-complexity manufacturing currently handled out of China. Given its already strong trade relationships with the Chinese economy as well as geographic proximity, manufacturing shifts, and supply chain, rerouting should be considered.

South Asia – major players, opportunities

The South Asia region is defined as an area consisting of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Both Bhutan and the Maldives have a labour force of under 1 million and will therefore be disregarded. Despite a labour force of more than 14 million, Afghanistan has also been disregarded due to its volatile security situation.

Apart from India, which is a major potential labour market, this section will also discuss Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka in terms of their manufacturing relocation potential.

Let’s start by taking a look at India, one of the more obvious choices to diversify manufacturing capacity away from China.

So, India has a large, well-educated workforce and is poised to take over from China to become the world’s next workbench, right?

Well, before drawing a conclusion on India’s suitability and readiness to take over, it is worthwhile to look at a few more fiscal and economic parameters, starting with FX rates and inflation.

India: rupee vs US dollar exchange rate/inflation

Driven by uncertainty surrounding the lack of market reforms as well as political risk, interest rates steadily rose prior to 2014. However, this perception changed with the Modi government implementing further market reforms along with fiscal discipline following its 2014 election.

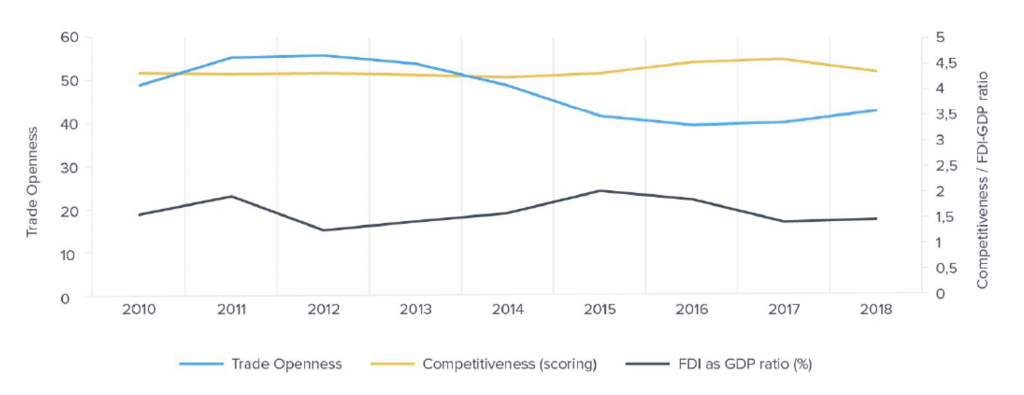

However, this momentum came to a halt after 2016, when government policies such as demonetisation (cancelling of large banknote denominations) and the introduction of the goods and services tax stifled domestic consumption. With the continued stellar recovery trajectory of western markets, FDI investors decided to leave or pass on investments in India.

India: comparison of trade openness vs competitiveness vs relative foreign direct investment

Bottom line (South Asia)

India provides significant replacement opportunities for manufacturing capabilities and to repeat the success demonstrated by its outsourcing and IT sector over the past two decades. However, significant issues remain — notably, enhancements and privatisation of the bloated government sector, gender issues, lack of suitable infrastructure, and bureaucratic hurdles.

Despite all these, I believe that the comparably lesser frictional potential between India and the western world will refocus the West’s attention toward the Indian economy and consequently provide significant opportunities for investors.

This concludes the Part 1 of our discussion of potential manufacturing relocation opportunities beyond China. Next week’s Part 2 will look at other suitable areas in South and South-east Asia as well as Sub-Saharan Africa.

Stay tuned!

This article was originally published in May 2020 on Toptal and is here republished with permission