China’s position on the world stage is changing rapidly as it moves to become a strategic competitor to incumbent economic powerhouses. Not least because of the recent trade conflict between the US and China and its long-term fallout as well as the covid-19 outbreak, it is imperative for companies to recalibrate their manufacturing relationships with the Chinese market.

Part 1 of this two-part miniseries, published last week, discussed the global importance of China’s manufacturing sector and relocation opportunities in East and South Asia.

Today’s part 2 will look at other suitable manufacturing locations in South and South-East Asia as well as Sub-Saharan Africa.

How about other countries in South Asia?

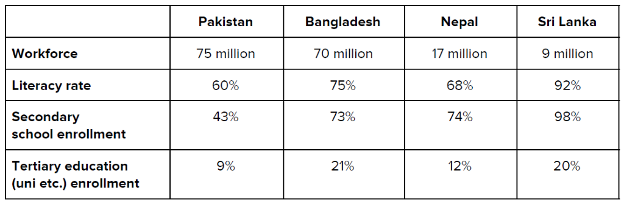

South Asian countries outside India provide a young and plentiful workforce which opens up opportunities for investors to expand manufacturing. However, political instability and the lack of infrastructure represent significant investment hurdles.

Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, however, show signs of economic improvement, driven in both cases by the garment industry and improved trade liberalisation. The comparatively high educational achievements in Sri Lanka should allow expansion into the service sector or higher-value manufacturing. The same applies partially to Bangladesh.

Nepal has become a major labour exporter to traditional target markets like the Middle East – but increasingly also to European markets, easing their lack of qualified labour. Once the country manages to reverse this trend, local manufacturing hubs would certainly profit. Pakistan, as the biggest labour market in the region, together with China, enacted the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to invest $60bn in energy generation and infrastructure projects and with the declared goal of achieving growth rates in excess of 6% per annum. It remains to be seen how these projects will materialise and allow manufacturing (and service) investors to tap the significant expansion potential the market has to offer.

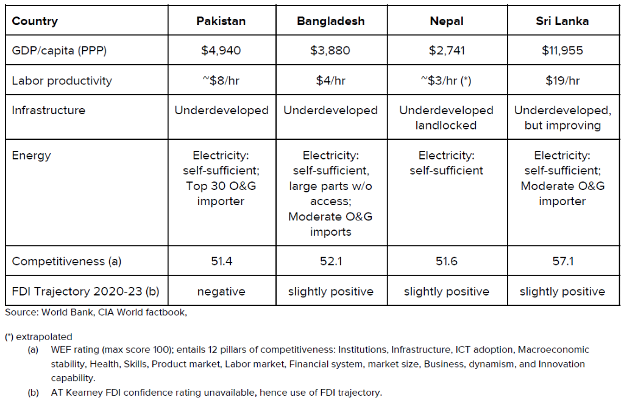

FDI trajectory: Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal

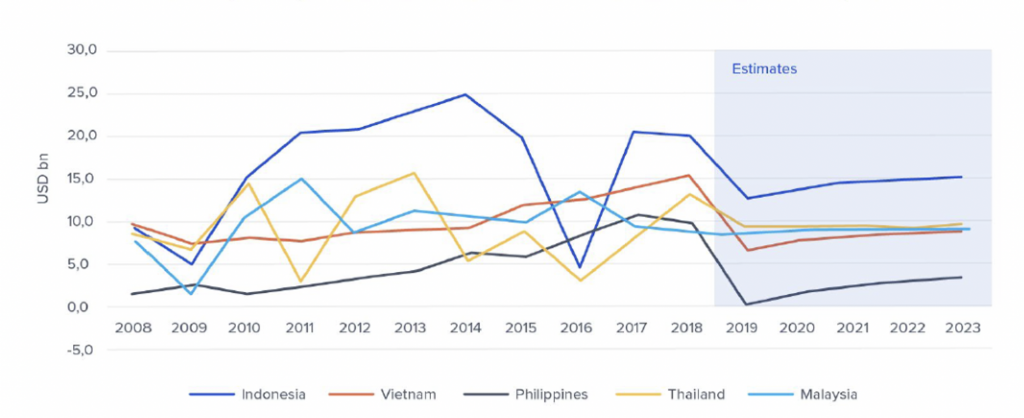

South-east Asia and the Pacific – major players and opportunities

Given their proximity to existing manufacturing hubs in southern China, South-east Asian countries are natural candidates for companies looking to diversify their China-only supply chains. Initially driven by the US-China trade animosities, the post-covid world will see increased soul-searching and action to diversify exposure.

Major SEA labour markets with manufacturing relocation potential include the following:

(a) WEF rating (max score 100); entails 12 pillars of competitiveness: Institutions, Infrastructure, ICT adoption, Macroeconomic stability, Health, Skills, Product market, Labor market, Financial system, market size, Business, dynamism, and Innovation capability.

(b) AT Kearney FDI confidence rating unavailable, hence use of FDI trajectory.

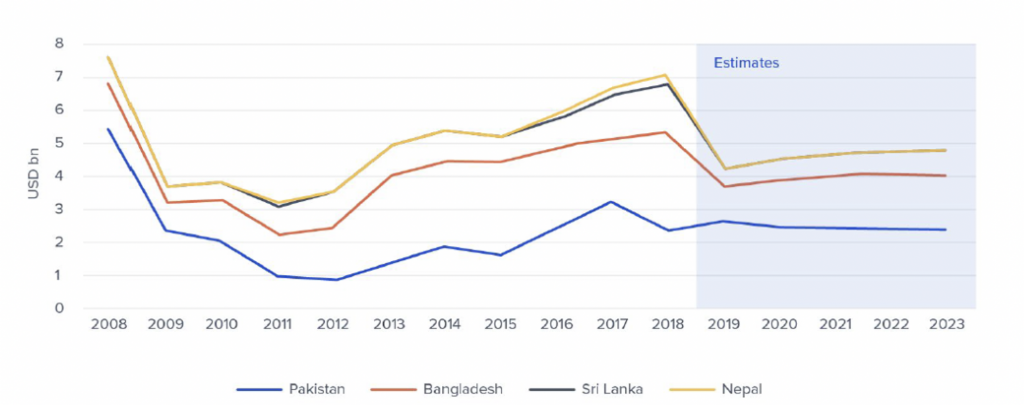

FDI trajectory: Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia

Bottom line (South-east Asia and the Pacific)

In particular, Vietnam has seen tremendous advancements in its GDP growth rate during recent years, exceeding 7% in 2018. Samsung, for instance, has poured more than US$17 bn of FDI into R&D and manufacturing facilities in Vietnam, making it its major cell phone production hub worldwide. Total South Korean investments are exceeding US$60bn, closely followed by Japan and Singapore-based investors. There is also an increased interest by Chinese investors to shift production to Vietnam in order to hedge against tariffs imposed by the US.

Nevertheless, common obstacles like insufficient infrastructure, energy shortfalls, corruption and a difficult-to-navigate tax and regulatory framework provide significant hurdles for expansion of both domestic entrepreneurs and foreign investors. Regional instability like the ongoing dispute between China and Vietnam/the Philippines about territorial claims in the South China Sea, impacting access to natural resources and international shipping routes, adds additional layers of complexity. However, the impressive progress that countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia have made recently looks promising. The combination of a young and available workforce along with a solid educational framework should definitely put them on the radar for international investors seeking to diversify their supply chains.

While the world’s eyes have primarily been trained on Asia in the past, going forward, another particular region stands out with significant potential to become an alternative manufacturing hub.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan African countries represented approximately 12% of the global labour force in 2018, according to the ILO. However, the next ten years and beyond are poised for significant structural changes in the availability of global labour, which is primarily driven by demographic disparities between Western and Asian countries on the one hand, and sub-Saharan countries on the other.

This medium- to long-term trend is reflected in the following three simple charts.

1) Relatively high birth rates in Sub-Saharan Africa are resulting in a significantly lower median age across the region. While this will provide significant challenges in terms of nutrition, urbanisation/housing, water resources, reliable electricity, access to education, and political stability in general, it is also a distinctive competitive advantage compared with the rest of the world.

2) As a result of these demographic shifts, the region’s share of the global labour force will almost double by 2030 compared with 1990. Given the growth trajectory, this trend is likely to accelerate beyond 2030.

Share of global labour force by region, 1990 and 2030 (%)

3) Given the significant share of (small-scale and relatively inefficient) agricultural employment in most sub-Saharan countries, a similar labour migration into manufacturing employment as observed in East and South-east Asia over the last three decades is a possible scenario.

Bottom line (Sub-Saharan Africa)

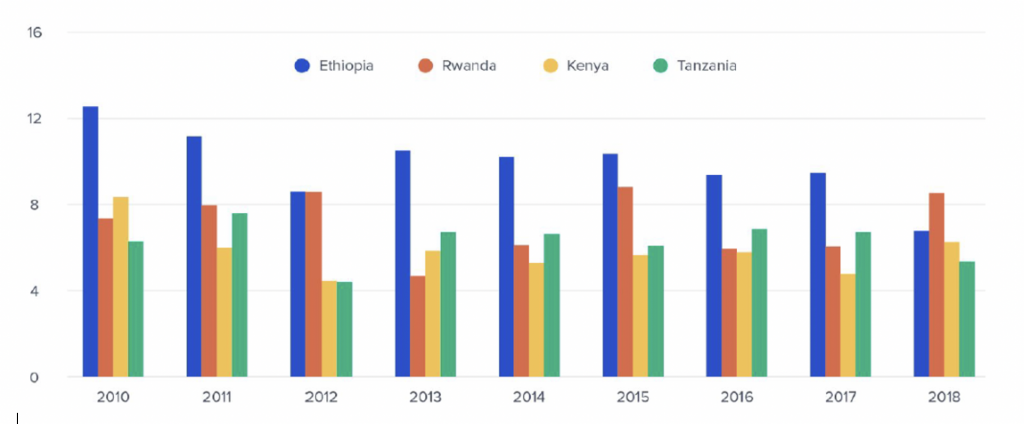

While significant obstacles remain for Sub-Saharan Africa to cash in on its demographic dividend, success stories like those of Rwanda, Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania are encouraging and should definitely put these and other regional markets on the menu for manufacturers looking to diversify and de-risk their supply chains.

A particularly interesting industrial cluster is evolving around the Red Sea combining various KSA-based industrial cities (KAEC, Jazan, etc) with access to cost-effective energy sources and extensive labour markets in North and East African countries.

Economic growth: rate of change of real GDP

Conclusion

That’s the end of our ‘Phileas Fogg – around the world’ search for alternative locations to diversify supply chains. As the world is emerging from its covid-19 standstill and facing an increasingly hostile relationship between the US and China, it is high time to future-proof businesses for a much more volatile economic and geopolitical future.

As we have seen over the past couple of months, well-diversified and redundant supply chain structures are, and will remain, crucial to weather future storms and as such should move to the top of senior executives’ to-do lists.

This article was originally published in May 2020 on Toptal and is here republished with permission.