This article was originally published in April 2019.

The birthplace of the skyscraper overflows with famous buildings – but none as stunning as a lesser-known piece of architecture, Bertrand Goldberg’s brutalist ‘city within a city’.

A recent architectural field trip with my company, Derwent London, took us to that city that boasts the birth of what was then called the ‘cloud-buster’ – better known today as the skyscraper. Chicago was also home to the first

in1969 at a cost of $100m. Now known as 875 North Michigan Avenue, this 2.75m sq. ft colossus is still the city’s fourth-tallest building. A trip to the building’s Willis Tower Skydeck on the 95th floor, which offers a 360° view of the city, is a must-do on any trip to Chicago.

Also worth a visit are some earlier buildings by Louis Sullivan, including the Chicago Stock Exchange (built in1894) and the Sullivan Center, which became a temple of commerce; each made a distinct contribution to the architecture of the city. Of course, you can’t discuss Chicago’s architecture without a mention of Mies van der Rohe’s amazing 860-880 Lake Shore Drive or his Illinois Institute of Technology – or, for that matter, of Frank Lloyd Wright’s various buildings. These include Frederick C. Robie House, which its architect described as the “cornerstone of modern architecture”, the redesigned Rookery Building and the near century-old Unity Temple, which is one of the last surviving Prairie School buildings intended for public use. Chicago truly is a mecca for early modernist architecture.

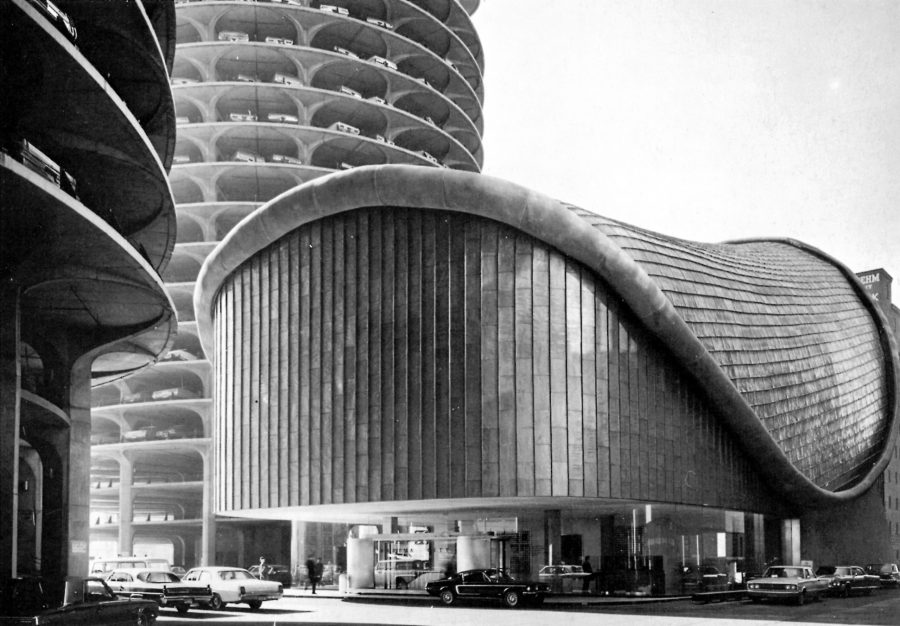

Spoilt for choice, I have opted for one of the city’s lesser-known architects, Bertrand Goldberg, and his spectacular Marina City complex, as one of my all-time favourite

Each of the two towers contains more than 400 pie-slice-shaped apartments. When completed, they became the tallest reinforced-concrete structures in the world. Fair-faced concrete played a major role, because it enabled Goldberg to explore the potential of curvilinear and circular form and saved between 10% and 15% of the cost compared with using steel. The completed buildings are nothing short of astonishing. Nicknamed the Corn-on-the-Cob buildings, their bottom 19 floors form an exposed spiral parking ramp with 896 parking spaces, with the 20th floor containing a gym and laundry room with panoramic views of the Chicago Loop. Atop the apartments, a 360° open-air roof deck lies on the 61st floor (the top storey, not including the mechanical penthouse).

On each residential floor, a circular hallway surrounds the elevator core. Living areas occupy the outermost areas of each apartment, with every unit terminating in a 175 sq. ft semi-circular balcony, separated from the living areas by a floor-to-ceiling window wall. Due to this arrangement, every single living room and bedroom in Marina City has a balcony. The apartments are also unusual in that they function solely on electricity – a big environmental plus.

These brutalist towers won my instant admiration; their regular rhythm is mesmerising: ten-storey high, thin vertical strips of glass alternate with vertical concrete mullions – the contrast is striking. With the resurgence of Chicago’s urban culture in the late 1990s, Marina City rose in prominence as a popular escape of urbanity and modernity – endorsing the fact that great architecture invariably lasts the test of time. On looking up at the towers, it’s a dizzying perspective: a minimalist masterpiece with brilliant structural engineering at its core. I feel privileged to have visited this spectacular piece of modernist architecture and surprised that more people are not aware of the work of a great architect called Bertrand Goldberg.