“A railroad station? That was sort of a primitive airport, only you didn’t have to take a cab 20 miles out of town to reach it.” Reading through a recent Economist article discussing the runaway success of the Chinese high-speed rail network, I recalled this quote attributed to Russell Baker, the Pulitzer Prize winning New York Times columnist.

Reflecting on a year of intermittent covid lockdowns, I couldn’t help but wonder whether the answer to managing the ‘new normal’ of distributed working would become much easier to find if we were to refocus our connectivity efforts on improved rail services, similar to China.

Looking through timetables and maps, I soon recognised both the incredible achievement of China and the potential for Europe and the US. Let’s pick an example to illustrate this thought. The 2,100km (1,300-mile) journey between Beijing and Guangzhou in the south takes just eight hours, while the 1,300km (~800-mile) leisurely train ride across the EU between Bruxelles and Warsaw consumes 13 hours… on seven different trains. Travel.ing a similar distance by train between New York’s Penn Station and Chicago takes at least 17 hours… on three different trains and a Greyhound bus.

What did the Chinese get right and to what extent can it be replicated in Western markets?

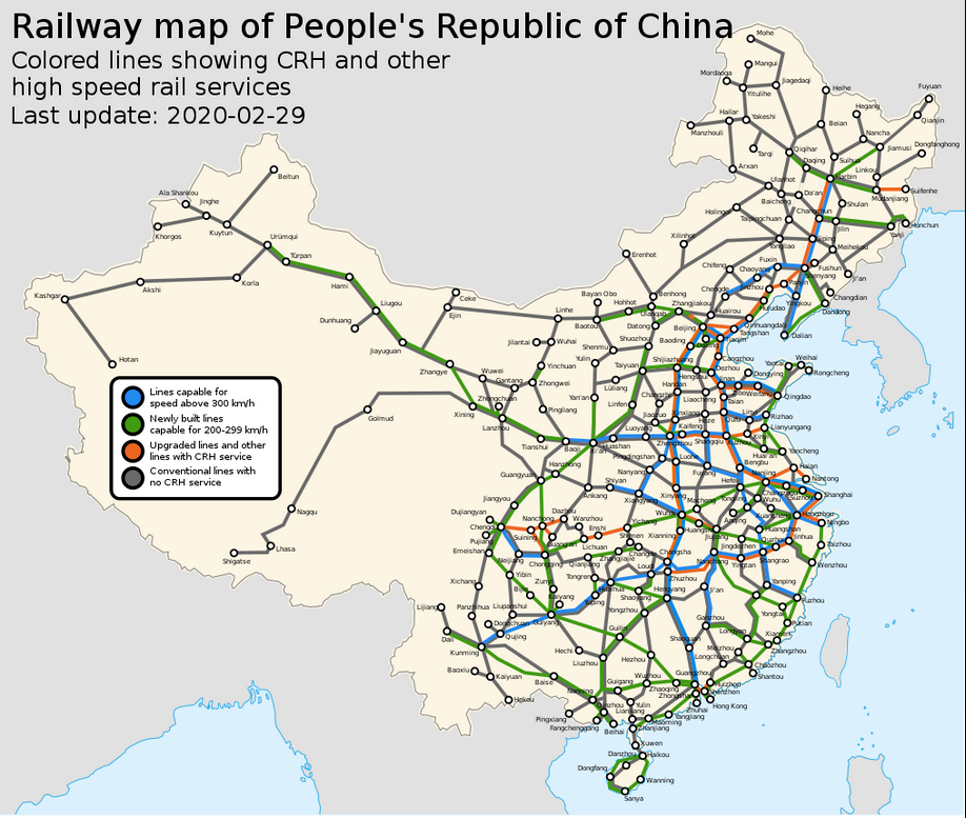

Source: Wikipedia

Let’s take a step back and consider the scale of the achievement.

China has the world’s largest network of high-speed rail lines with a total of 23,688 miles (38,122km). This represents 66% of the world’s HS rail tracks. The EU has roughly 18,300km of HS rail operational, the US and the UK (HS1) operate 362km and 113km, respectively.

Initially the People’s Republic of China’s national rail plan envisaged a grid of four north/south and four east/west lines. Its first line opened in 2007 and now the national network operates 3,112 daily services, reaching all provinces except Macau. The country’s latest national rail plan envisages a grid of ten north/south and ten east/west lines by 2035, doubling the HS network to 46,000 miles (74,000km).

At 1,300 miles (2,100km) Beijing-Guangzhou is the world’s longest HS run, connecting the two cities in eight hours at an average speed of 163mph (262km/hr). This speed would do London–Berlin in five hours and 30 minutes and London–Edinburgh in two hours and 30 minutes. Considering airport commutes and pre-flight entertainment at security checks, this would make pan-European air travel almost obsolete as well as enhance travel quality and productivity.

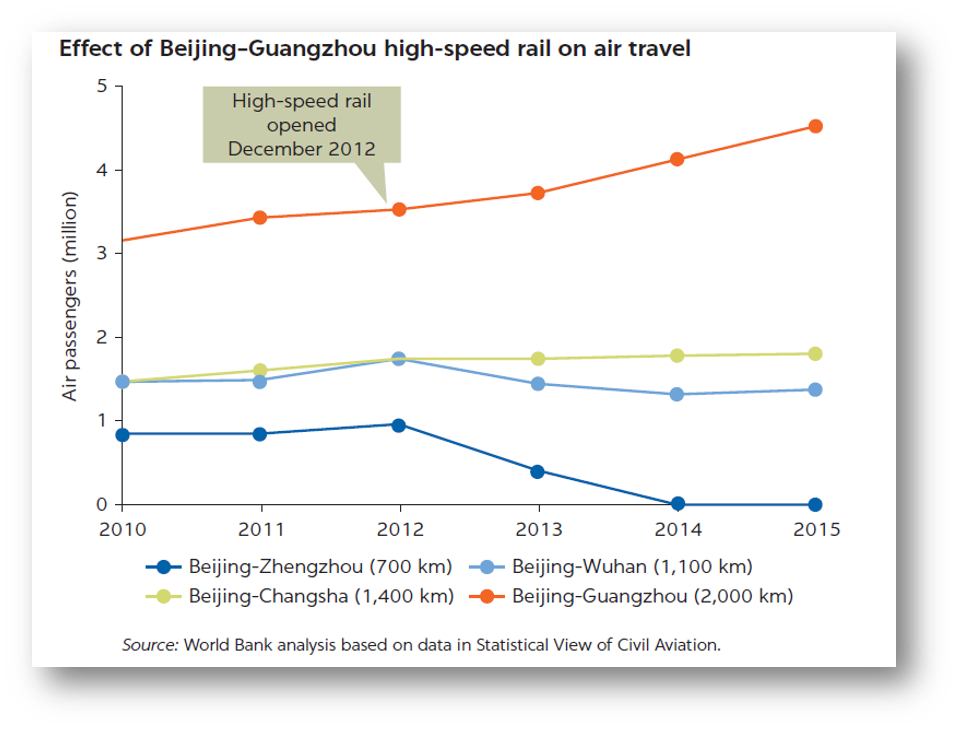

Observations on the sensitivity of air travel demand due to newly opened routes of the Chinese HSR network provide important clues to traffic planning worldwide, according to a 2019 World Bank analysis. Given the ‘green deal’ aspirations of both the European Commission and the Biden Administration, in a post-covid world this would add another strong consideration.

More importantly, though, HSR networks transform the ‘fly-over areas’ in between metropolitan areas in well-connected extensions and relieve some of the urbanisation pressure.

How did China achieve in two decades what Western countries didn’t manage despite a technological head-start?

Apart from the obvious political focus and sponsorship, the amazing construction speed (one new line opened annually) is mostly owed to state ownership of designated construction land and simplified planning processes. The impact has been illustrated in another recent Property Chronicle article discussing the state of public works in Germany.

Another interesting element of the PRC’s high-speed network is the fact that China decided it was not feasible to upgrade its classic railways for high speed at the time. Hence new lines were justified in order to enhance passenger mobility and, no less importantly, to release capacity on classic lines for freight expansion, in particular with respect to its massive Belt-and-Road project.

Was it just a daydream of the Central Planning Commission or part of the often-cited Chinese long game?

What started as the so-called ‘high-speed-rail-dream’ after Deng Xiaoping’s visit to Japan in 1978 witnessing the Shinkansen, the world’s first HSR network, soon evolved into a wider national debate and an intermediate solution aimed at increasing existing lines’ capacity by enabling higher speeds allowing for enhanced service frequencies.

Objective #1: Urbanise China and transform the country from a rural widely dispersed culture to an urban trading culture by moving people into urban clusters interconnected by high-speed rail networks.

Objective #2: Improve national productivity and international competitiveness.

Objective #3: Release capacity on classic lines to be used for freight traffic.

Objective #4: Short/medium/long-term economic stimulation by creating jobs/industry/tech clusters.

Objective #5: Even up regional economies and allow second-tier cities to expand.

Objective #6: Develop high-speed technical capability (rolling stock, signalling) but also HS rail construction capabilities and references for export.

Was it worth it?

Quantifying economic impacts of an infrastructure project of this magnitude is tough.

MacroPolo, the China-focused think tank of the Paulson Institute, calculates the net economic benefit of the high-speed rail network to China’s economy at $378bn, which translates into an annual return on investment of 6.5%. The assumptions made appear reasonable and are in line with the World Bank study cited above.

Another insightful analysis, prepared by the Asian Development Bank, compares different economic impacts of HSR networks in the UK (HS1) and Suzhou, a 10 million population metropolitan area about 100km west of Shanghai. Since agglomeration is often cited as major urbanisation benefit, the arrival of HSR with multiple stops in the larger Suzhou area demonstrated the HSR’s disbursement effects, while maintaining the agglomeration benefits. This applied primarily to knowledge-based industries and holds interesting lessons for the current hybrid WFH and satellite office discussions.

What are the takeaways for Europe, America and others pursuing HSR networks?

There is no ‘one size fits all’, as indicated in the comparative ADB analysis.

Large European cities, for instance, are more similar, tending towards conversion. This is in contrast to Chinese cities and, to some extent, American ones as well. Hence transport improvements, including high-speed rail networks, rather result in increased regional conversion.

Chinese and to some extent American cities, though, tend to have a higher degree of specialisation. Both markets also show a higher degree of flexibility. HSR networks therefore magnify these impacts, resulting in a higher degree of specialisation and divergence.

This obviously holds important lessons for future HSR projects in developed regions such as Europe or the US but also in emerging economies like Vietnam. Looking at the initial objectives laid out for the Chinese HSR network, a number of non-monetary motives and benefits emerge which will need to be taken into consideration when making the case for (or against) an HSR. The Chinese HSR, for example, but also similar projects like South Korea’s TGV network provide valuable insights, not least on creating a level economic playing field across the country.

It will be interesting to see what impact European and American HSR projects such as HS2 in the UK or the Californian HSR project will have, not only on affected economies, but also on the way people in major urban clusters live and work.

I would like to extend my gratitude to the various senior international rail experts who provided valuable input and guidance for this article.