It’s popular to group millennials together as one cohesive group and compare like-for-like. But they are a diverse bunch that share as many differences as they do similarities. Where comparisons are useful is in determining how this generation will drive future demand. After all, their contribution is largely baked into the demographic cake.

We find that while US millennials will continue to enjoy real income gains, the liabilities they’re on the hook for, combined with the damage inflicted upon them by the financial crisis, mean their contribution to demand won’t match earlier generations. That obviously has negative implications for growth. Chinese millennials share many of the demographic stresses of their US peers, but they will see faster real income gains and shouldn’t have to shoulder the same level of unfunded liabilities. This reinforces the reality that China will continue to drive an ever-increasing share of global demand growth. And there isn’t much the US can do about that.

ANALYSIS

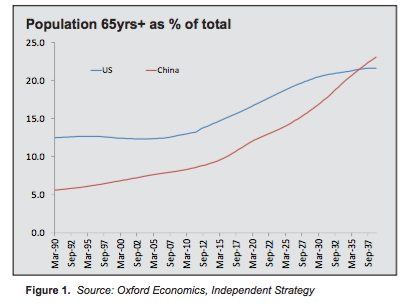

As demographic trends become a more forceful influence on the global economy, it’s a worthwhile exercise to examine how this will impact demand and how this marries with population aging. Both the US and China have reached a point where the share of the population beyond working age is surging (Figure 1).

In the US this is due to the increasing longevity of the boomer generation. In China these forces are amplified by the impact of the one child policy. How these pressures balance with demand from the upcoming millennial generation, which is the group that will shoulder a considerable amount of this burden, will vary considerably.

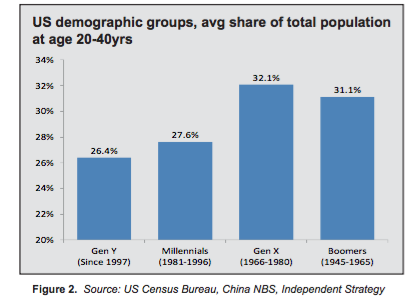

While the boomers — born between 1945 and 1965 — exit the working stage, millennials (born 1981 to 1996) are now starting to enter the peak consumption phase of life (35-55 years old), an age when people traditionally begun to settle down, buy a home and raise a family. As a group, in both China and the US (and other DMs), they represent a much smaller wedge of the total population than earlier generations, most notably the boomers, but also the Gen Xers that arrived between 1966 and 1980 (Figure 2). But their position means they remain the biggest influence in determining the domestic and global economy’s underlying rate of demand growth.

This is where things become slightly more complex, as to determine the transformative impact of each country’s millennial cohort, one also needs to factor changes in consumption elsewhere in the demographic profile. While the aging boomer bracket makes the classical demographic pyramid more top heavy — reflecting both the size of this cohort and the progress (if you can call it that) made in longevity — the costs of these shifts vary depending on a number of variables. These include location (intra-country), the availability and adequacy of social safety nets and the level of savings, as well as the more obvious income growth trends.

Many of these should net off to an extent, but the residual balances will determine how much burden sharing — in the form of intra-generational transfers from millennial workers to boomers in their dotage — need to be made. Where there are large unfunded liabilities, particularly in the case of health and pension provisions, the implications for millennial income and consumption could be significant.

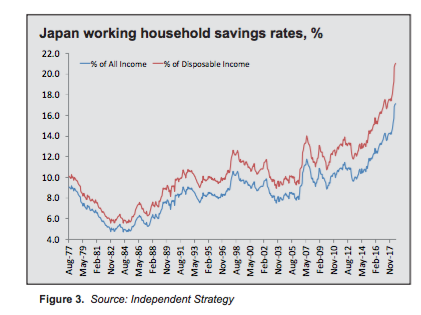

This is already evident in Japan, where demographic trends are further advanced. Pensioners (over 65s) now make up 27% of the population, a level China and the US won’t see until the second half of this century. This has boosted Japanese social security spending from 20% of government revenues in 2000 to nearly 35% today. While Japanese millennials’ employment prospects look great and income levels have started to increase after decades of stagnation due to the tight labour market, domestic demand remains lacklustre. Instead, worker household savings rates have gone through the roof (Figure 3). This reflects Japan’s incredibly low birth rate/shrinking population as well as longer-term uncertainty surrounding the country’s sovereign indebtedness and the perception that the benefits enjoyed by the post-war generations won’t be around when the current working cohort comes to retire.

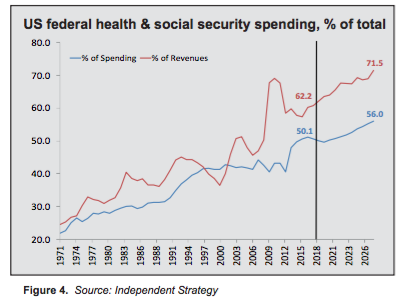

As for the US, based on CBO forecasts, the impact of rising government health and social security expenditure is significant over the course of the next decade. Outgoings are set to rise from 10.4% to 13.1% of GDP. That would take social spending to 56% of the total, soaking up over 71% of total federal revenues (Figure 4). And this is all focused on the boomers, with the increase driven by Medicare (rather than Medicaid) and Social Security. Moody’s sees the current Social Security funding gap at $13.4trn, while the shortfall just from the Hospital Insurance component of the Medicare programme is another $3.2trn.

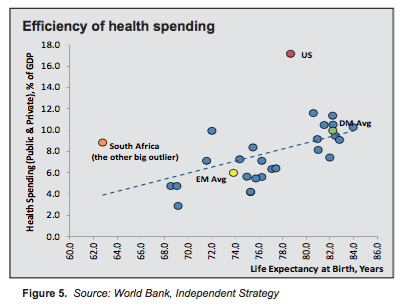

Health is the one sector of the US economy that stands out as parasitic, with ideologic opposition to public programmes and the taxation this would require, deeply embedded. This pretence contrasts with the efficiency that public health systems provide in every other developed country. And for the extra 7.2% pts of GDP the US spends vs. the DM average (Figure 5) — a staggering US$1.47trn per year — it delivers lower (now falling) life expectancy and poorer health outcomes (albeit with more in-room TV, fruit and flower options, if you’re insured).

On the pension side, many public employee pension schemes have serious solvency issues. Moody’s thinks public defined-benefit pension schemes (federal, state and local government plans) already have a combined deficit of US$7trn. And that’s despite a big increase in contributions from the States and a decade-long equity bull-market. While benefits have been cut and retirement ages pushed up for younger workers, it’s the cost of covering existing or near retirees that accounts for the bulk of the problem.

All in, the current US pension and welfare (assets – liabilities) gap is equivalent to 115% of GDP! Of course, this doesn’t need to be made up in one shot. But based on the 7-8% p.a. return most pension funds say they need in order to honour their liabilities, versus expected returns closer to 3-4%, it would still imply a net annual funding shortfall of around $700bn, or over 3% of GDP. Closing the gap would require a combination of increased contributions, recipients working longer (or living shorter!) and lower benefits. But such reforms are not likely to be forthcoming voluntarily. Consequently, the pensions gap will to continue to grow.

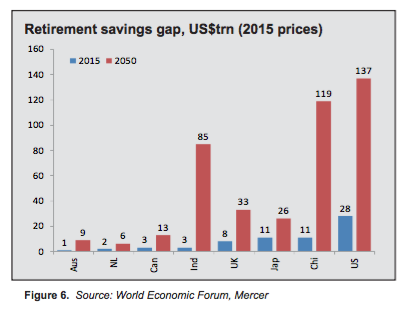

or the US as a whole (public and private), the World Economic Forum places the retirement shortfall at US$28trn and sees this rising to $137trn (in 2015 prices) by 2050 —which is an even gloomier prospect. But the US won’t be alone. Pension shortfalls are evident globally, including in countries that have far more established defined-contribution systems. China also faces a substantial pensions gap, currently penned at $11trn and seen rising more than ten-fold to $119trn by the middle of the century (Figure 6).

But this isn’t actually as bad as it sounds. If US millennials were still eating avocado toast on their lunch breaks in 2050, they’d find that they’d have $10trn of income to play with in today’s dollars, versus around $3trn currently. But that would still translate into a 34% rise in the real pension shortfall versus today. In contrast, Chinese millennials could afford a far larger serving; the real value of their pension shortfall has shrunk by a quarter thanks to faster income growth.

Arguably, the Chinese picture is even more positive given the social differences between the two countries, notably the relative wealth of the post-war generations born in China and the US and consequently differing expectations these people have for their twilight years. In China, the elderly are also concentrated disproportionately in (less developed) rural areas. Traditional family support structures, long established thanks to the lack of cohesive national health and pensions systems, are a further safety-net. In a nutshell, it will remain far cheaper to keep a Chinese pensioner in old age than a US one, irrespective of the one child problem.

This might all seem rather irrelevant to millennials’ futures. But it underlines that the millstone effect — that comes from the unique period of population aging we’re entering — varies considerably. That is helpful when looking both at the underlying level of wealth and the demand the millennial generation should be able to generate.

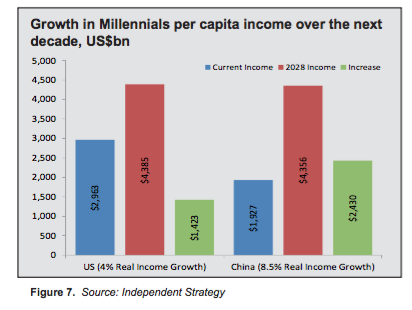

While millennial income levels in the US are many multiples of those in China, due to the size of China’s population and higher rate of real income growth, it’s actually China that’ll be fuelling demand. US millennials’ per capita income should rise from just under $3trn today to around $4.3trn over the next decade, but in China incomes will more than double (from US$1.9trn to US$4.4trn), outstripping the US in dollar terms (Figure 7), if not on a per capita basis (that’ll take a few more decades). It wouldn’t matter much if these income assumptions were too high, the relative difference will remain.

In many respects, Chinese millennials have more in common with the US boomer generation than they do with their direct American peer group. They’re far better-educated than their predecessors, they are entering a rapidly-developing consumer economy (similar to post-war US) and, relative to their own parents, face fewer personal restrictions on their lives.

Liberty in an authoritarian state is always going to be restricted, but thanks to access to the communication technologies of the internet age, knowledge and information has been democratised to a far greater extent. Perhaps more so than even in post-war America. That depends on whether you place more value on the independent editorial observations of the mainstream media or having access to raw footage of events, shared uncensored and commented via instant messaging and social media apps.

Equally important for demand could be the easing of the one child policy, as the government seeks to counter the risk that China becomes old before it gets rich; assuming this policy can actually generate a baby boom. All of these factors will contribute to stronger domestic demand over the coming decades.

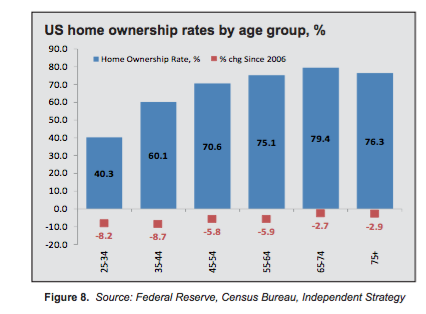

Contrast this with the US. While in real terms they’ll still get richer, US millennials lack critical mass and have struggled with the legacy of the financial crisis. Job creation has bifurcated between high- and low-income jobs, forcing middle-class entrants into lower-skilled work. Student debt has increased rapidly as this group sought to re-skill to counter these trends. At the same time, home ownership rates collapsed (Figure 8).

That’s partly due to more restrictive lending practices put in place after the bust. But housing also lost its lustre (as things do when they stop being one way bets), encouraging millennials to defer buying. Now the market has recovered and thus seems a more reliable investment again, this group finds itself facing both higher prices and rising mortgage rates. Rents are also rising, further squeezing disposable income growth. While wages have begun to pick up, so has inflation, meaning in real terms earnings growth has actually been declining.

Absent any increase in productivity, these look to be persistent pressures for America’s generation rent. While some of the recent growth bounce will rub off, the fact it’s been generated with fiscal stimulus merely adds to the longer-term burdens millennials face. At some point these are going to have to be met with either higher taxes or lower spending.

INVESTMENT OUTLOOK

The divergence between US and Chinese growth rates casts a lengthening shadow over the US economy. And underlying rates of demand growth will diverge sharply in the coming decades as US liabilities land on a generation that looks ill-equipped to pay for them. We can already see how demand can react to these pressures from Japan’s experience: consumers retrench and adopt strategies that are even more counter-productive at a societal level even if not having children and saving more makes sense on a personal level.

China shares many of these demographic traits, but these liabilities look easier to manage thanks to differing expectations of old age and strong real income growth. While the US might see the rise of China as a threat it can counter with trade and other restrictions, the underlying reality is that America’s relative secular decline is baked in the cake. And the shift toward more nationalistic economic and foreign policies is a reflection of this reality, not the antidote to it.