“We don’t know what we don’t know,” as Donald Rumsfeld once said when asked whether intelligence gathered had been shared adequately across the US intelligence community. Applied to the economies of Africa, the meaning goes even deeper, since there appears to be a lack of economic intelligence on top of insufficient dissemination.

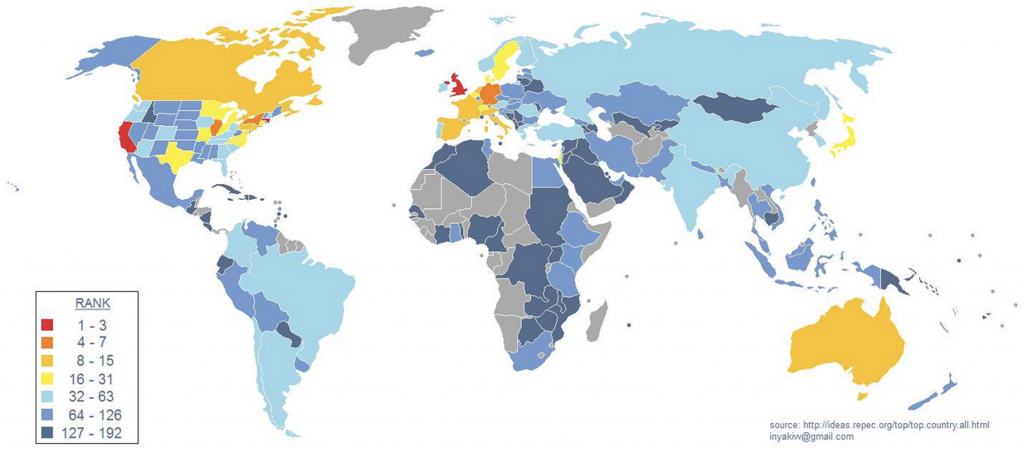

In 2009 the London-based data analyst Inaki Villanueva mapped global economic research density as shown in the map below.

Now, there is an argument to be made for the developed market-based research community to focus on data-rich developed economies.

However, large development institutions like the World Bank and the IMF with significant ‘boots on the ground’ in Africa are not doing much better in providing crucial data to support economic development and investment.

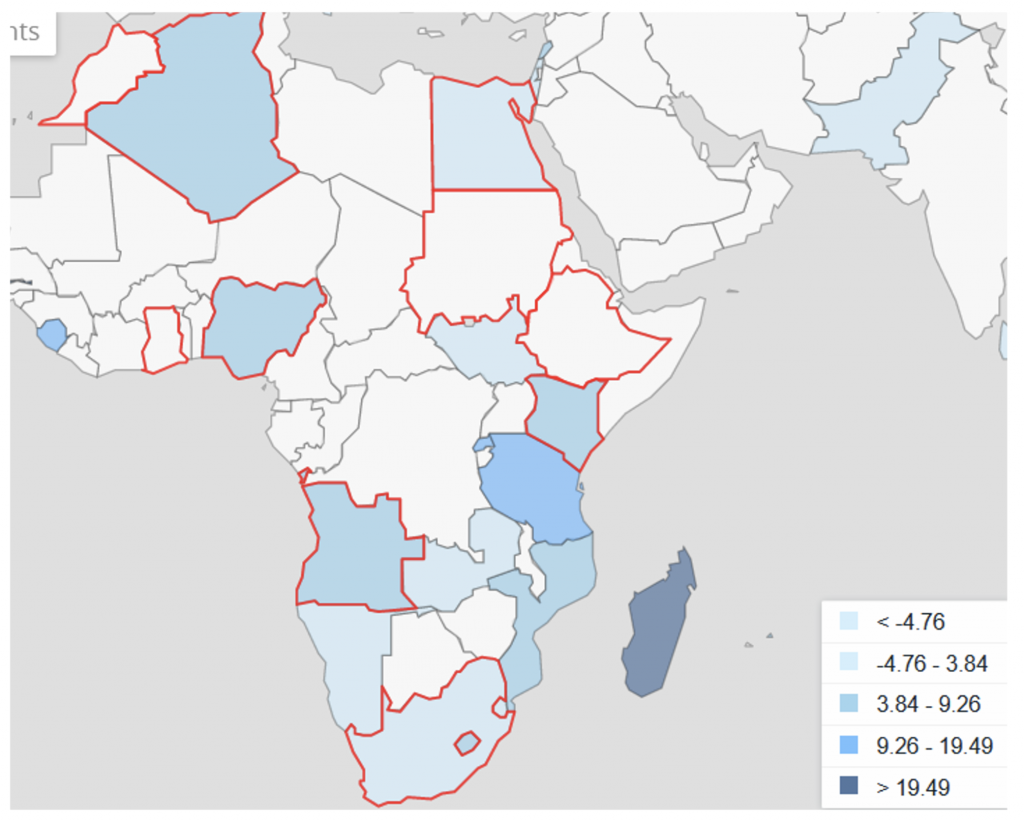

Looking through WB/IMF datasets on lending risk premiums for the ten largest African economies in terms of real GDP (PPP) reveals no data points for four markets (Morocco, Ethiopia, Sudan, Ghana) with a combined GDP of more than US$860bn.

Lending risk premiums for the ten largest African economies in real GDP terms

A similar picture emerges for the ten most populous African countries where no data on lending risk premiums is available for Ethiopia, DR Congo, Sudan and Uganda with a total of more than 300 million people. This is more than the populations of Germany, France, the UK and Italy combined.

Why does this matter for real estate and infrastructure investors?

A lack of reliable capital market data creates a lack of transparency, prevents real estate cycle observations and increases comparative risk perception, resulting in reduced investor appetite. Given their volatility and lack of track record, emerging markets in general and Africa in particular often fall victim to ‘judgement by perception’ as opposed to rational, data-driven investment decisions.

What does this mean for investors?

Opaque markets coupled with relatively high volatility typically favours low-constraint investors (LCIs). Compared with traditional fund management platforms, these LCIs typically act with comparatively long investment horizons, high volatility and risk tolerance. The latter applies particularly to complex, multi-phased projects in opaque environments and distress or turnaround situations. Long time horizons allow those LCIs to study the market by typically setting up a local or regional presence and by virtue of often being ‘the only gig in town’ to enforce quasi-monopolistic pricing power in terms of land acquisition costs, utility access and zoning adjustments.

Privately owned real estate development platforms capitalised by ‘LCI-style patient capital’ sourced from forward-thinking endowments, sovereign wealth funds or family offices tend to have an edge in these situations.

What do we know about African markets and how does this translate into investment ideas?

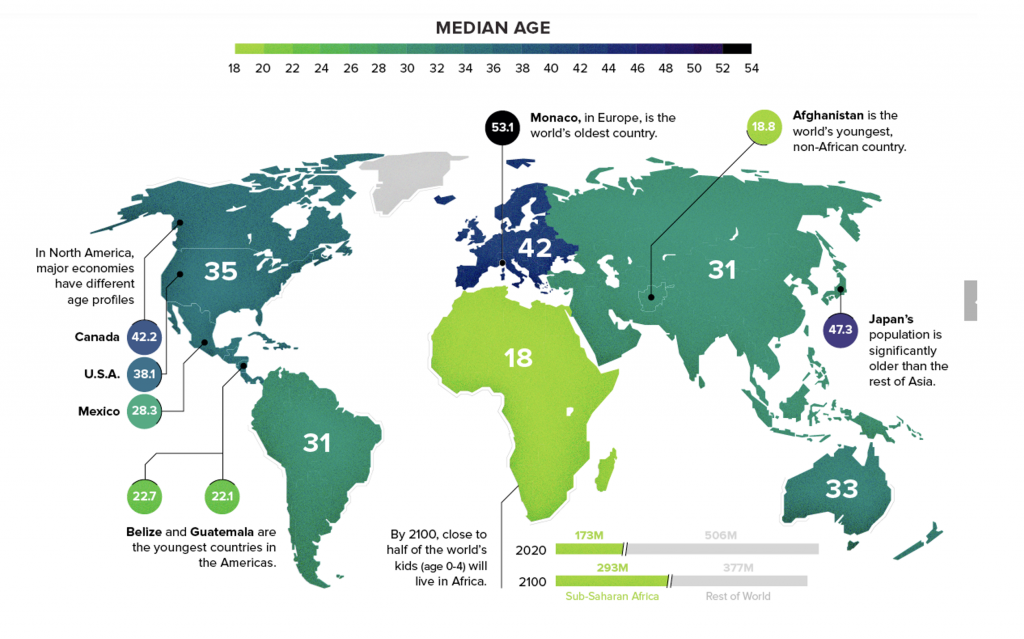

The overarching story, especially for Sub-Saharan Africa, is obviously demographics.

Relatively high birth rates in Sub-Saharan Africa result in a significantly lower median age across the region. While this will provide significant challenges in terms of nutrition, urbanization and housing, water resources, reliable electricity, access to education, and political stability in general, it is also a distinctive competitive advantage over the rest of the world.

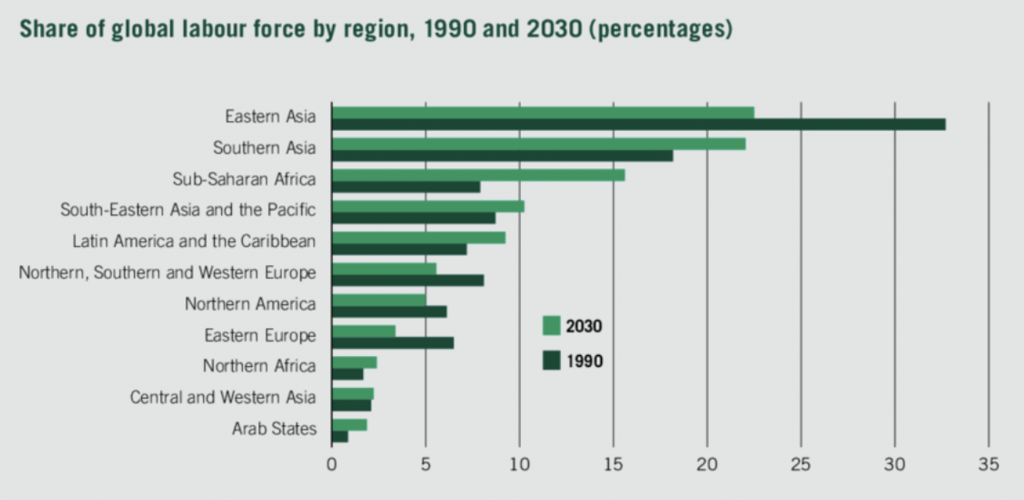

As a result of these demographic shifts, the region’s share of the global labour force will almost double by 2030 compared with 1990. Given the growth trajectory, this trend is likely to accelerate beyond 2030.

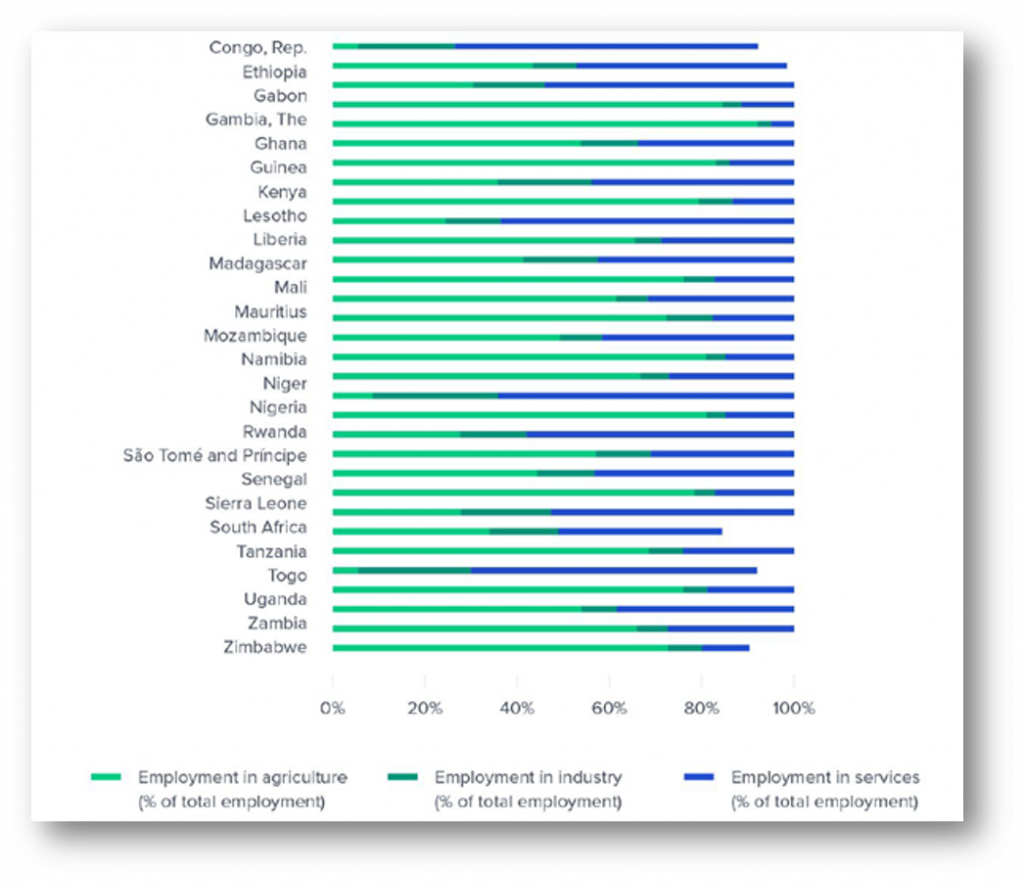

Given the significant share of (small-scale and relatively inefficient) agricultural employment in most Sub-Saharan countries, a similar labour migration into manufacturing employment as observed in East and South-east Asia over the last three decades is a possible scenario.

In terms of real estate product, I expect residential investments (including social housing) along with e-commerce logistics and data centres to perform best in the medium term. In a post-covid world, most African markets will benefit from the fact that adjustment processes like home-working or e-commerce will have less of an impact on existing real estate stock, since it simply wasn’t there before. This will allow more customisation during the design phase as opposed to later adjustments.

Given relatively patchy economic research data for a number of African markets, I expect one of the most profitable property investment areas to be not bricks and mortar but data-driven proptech solutions.

The lay of the land is visible. As the global ‘hunt for yield’ intensifies, ageing retirement investors especially in Western economies and China will need to tap the ‘demographic dividend’ in Africa. It remains to be seen whether some of the larger institutional investors leap to the challenge at scale and as such send a signal to the wider investment community, which could make it the ‘next big thing’.