Originally published January 2022.

As investment managers, we’re used to being accused of seeing the glass as half-empty rather than half-full. It’s not that we’re inherently pessimistic, but our job is to protect our investors’ capital against whatever might go wrong in markets. So naturally we tend to focus more on the risks than the opportunities. Or, as Jonathan Ruffer might put it, to see the mousetrap clearer than the cheese.

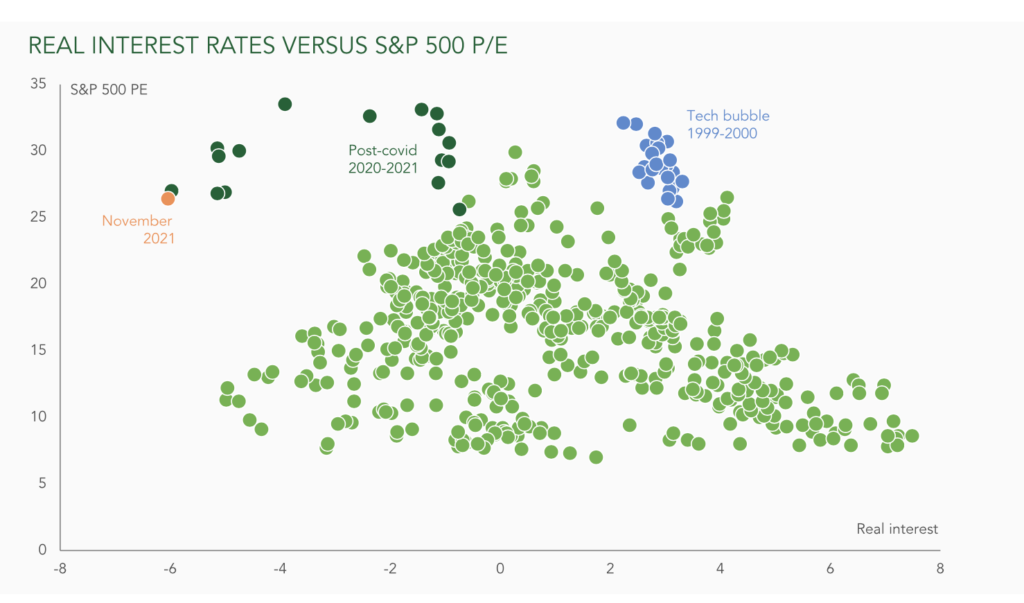

This month’s chart is aimed at countering the current idea that highly negative interest rates are supportive of sky-high equity valuations.

Historically, whenever real interest rates have deviated from the Goldilocks range of -2% to 2, stock market price-to-earnings ratios (P/Es) have fallen. The only exceptions being the tech bubble in 1998-2000 and the recent post-Covid period. The first ended badly. We must wait to see what happens this time.

This is all about the discount rate: the rate at which we need to discount future profits or cashflows to work out what they are worth today.

If interest rates and inflation are both zero, then the real interest rate is also zero, so we don’t have to discount future profits at all. Money received in the future is worth as much as money received today. Therefore, the valuation of equity markets, or the P/E ratio, can be justifiably high. This goes a long way to explaining high equity valuations, since interest rates were slashed after the credit crisis.

We know if interest rates rise sharply, markets are likely to fall, partially due to a higher discount rate. If interest rates jumped to 10%, then future profits from equities would have to be discounted at 10% a year. Bad news for all stocks, but especially for those where most of the profits and cashflows are expected to be paid in the distant future. The growth stocks, profitless companies and concept stocks so popular today would clearly be the hardest hit in such a situation.

What about the position today, with interest rates still close to zero, but inflation printing at over 6%?

Let’s use another extreme example. If interest rates remained at zero, but inflation was 10%, then we would have a real interest rate of minus 10%. The interest rate element of the discount rate remains wholly supportive of high valuations, but what about the inflation part?

If inflation is running at 10%, then there will be more uncertainty on both future earnings and future interest rates. In contrast to the current market conceit, this would demand a higher discount rate (and not a lower one). This implies a lower valuation for markets as a whole and potentially even worse news for those most highly rated growth stocks.

Our concern is if inflation stays elevated, even if central banks keep interest rates low, then current stock market valuations will prove far too high.

Yes, equities can be considered ‘real assets’, whose cashflows may rise with inflation. This makes them better than conventional bonds when inflation is high. But watch out for a de-rating that could cost investors dear.

With the recent holidays in mind, and to paraphrase Dickens, beware the ghosts of inflations past, present and especially future.

Originally published by Ruffer and reprinted here with permission.