We live in a world of virtual reality: virtual conversations, virtual relationships, virtual work, and virtual leisure. Artificial intelligence is on a mission to replace us all with avatars: bright, shiny versions of ourselves. Central banks have been busy creating a virtual financial world, comprising virtual balance sheets, virtual creditworthiness, and virtual financial asset prices. Governments, for their part, have chimed in with virtual budgets, virtual guarantees, and virtual promises.

According to the dictionary, virtual is “almost or nearly as described, but not completely or according to strict definition”. Hence, a mirage is a virtual oasis and a VAR-disallowed goal is a virtual score.

Melanie Reid, a columnist in the Saturday Times magazine – a must-read in our house – describes her virtual life as a tetraplegic, following a riding accident more than ten years ago. Her latest column articulates her belief that, within a couple of years, people will be begging to spend three days a week in the centralised workplace again.

The first problem with virtual is that it nearly satisfies us, but leaves us wanting more

The first problem with virtual is that it nearly satisfies us, but leaves us wanting more. The second problem is that it touches up the flaws and imperfections that are part of real life. That virtual tour of the stunning apartment is almost like being there, but it leaves out the cooking smell that wafts down the street from the oriental restaurant.

The good news is that, for a limited time only, owners of priced-for-perfection financial assets can exchange them on very favourable terms for real estate.

By virtue of heavy regulation of mortgage lending and rigorous enforcement of anti-money laundering provisions, global real estate has not been a significant beneficiary of monetary excess.

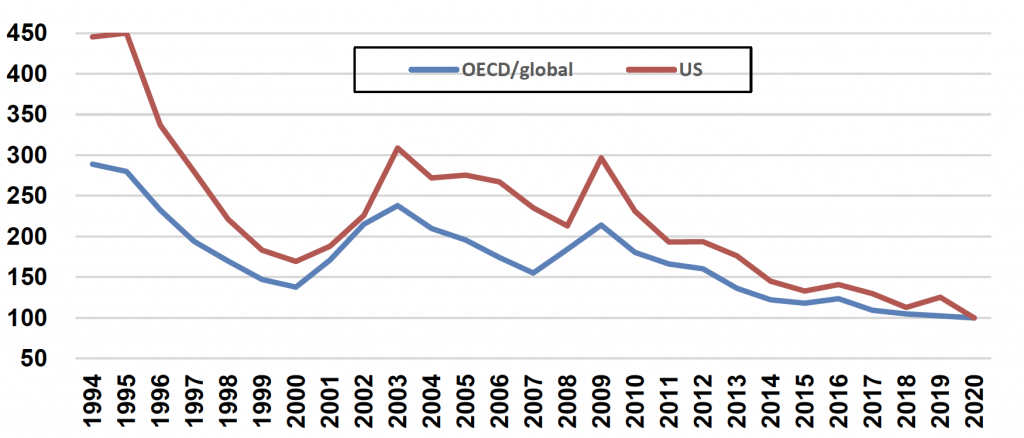

In fact, a diversified portfolio of global stocks will buy you twice as much advanced economy real estate as in 2009 and almost three times as much as in 1994. And, the great thing is, you can enjoy the view.

OECD average house prices to global equity return index and US comparator