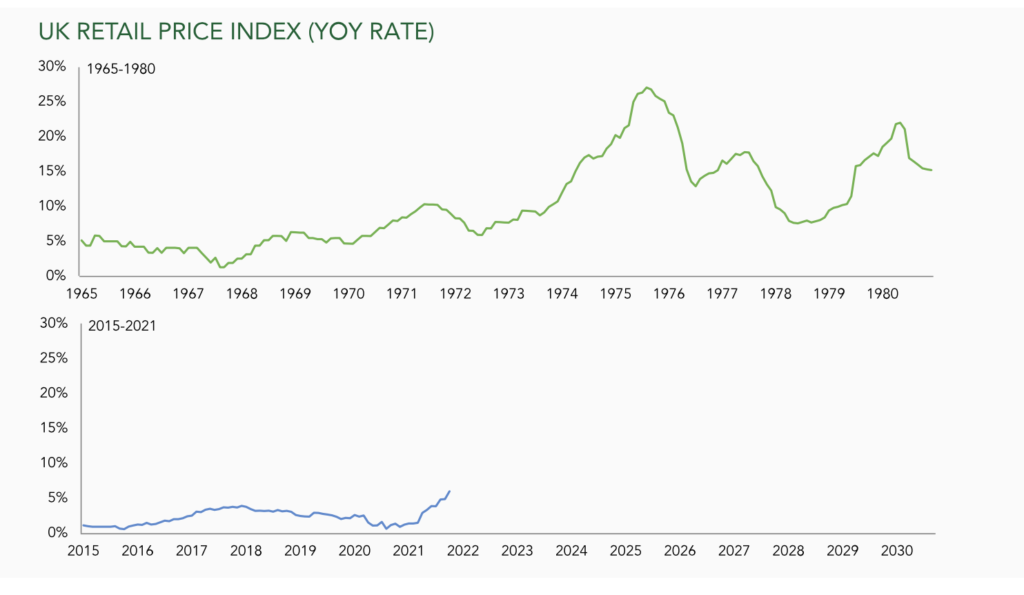

Investors have divided into two camps. Those who believe inflation will subside and the rise in prices will prove temporary, and others who fear we are entering a period of high sustained inflation reminiscent of the 1970s.

We consider both scenarios unlikely.

Overlay the bottom chart on the top and you would be forgiven for believing that we are now on the same trajectory as we were 50 years ago. There are parallels, but to assume the economy will meet the same inflationary fate would be a grave mistake for investors.

We believe we are entering a new inflationary era. But, unlike the 1970s, it won’t be marked out by shockingly high inflation rates. Instead, investors will confront a world of inflation volatility. In this environment, the gap between interest rates and headline inflation will widen – creating a dangerous chasm known as negative real yields.

Take energy prices, wages and interest rates. On first glance, the music sounds quite familiar. But closer listening reveals that we may be at a different concert altogether.

Rising energy prices were chief among the culprits in sparking inflation in the 1970s. And, while oil and gas prices have more than doubled in the past year, the world is not likely to see the 10-fold increase in energy costs that triggered the 1970s inflation (Reuters).

Wages are less likely to spiral. The past 40 years witnessed an extraordinary expansion of the global labour market – in effect, screwing the lid tight on wage inflation. The political, technological and social forces which suppressed wages may now be dwindling, but these forces are measured in decades, not months, and so we shouldn’t expect wages to spring up from the depths. Labour market dynamics have changed. When Britain’s coal miners ended their 1972 strike by accepting a pay increase of 35%, roughly 50% of the workforce was unionised. Today that has fallen to 24% (National Statistics DBEIS [Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy]).

Interest rates may rise – but they can only rise so far. By 1979, interest rates in the UK reached 17% (Bank of England). A year later, rates surpassed 18% in the US (St Louis Fed). But this time around, the firepower of central banks is limited – that is what we should be worrying about.

The world economy is more vulnerable to (and intolerant of) interest rate increases than it used to be. The government debt to GDP ratio for developed economies has risen from 20% in the 1970s to over 100% now (GFD [Global Financial Data], Deutsche Bank). Put simply, governments have become addicted to zero-cost borrowing and cannot afford for it to increase. And with asset prices also anchored to zero rates, it looks impossible for modern central banks to raise rates much without sending shockwaves through bond and equity markets.

This is how negative real yields come into play. The latest US CPI release means that the Real Fed Funds Rate (the difference between headline inflation and the Federal Open Market Committee’s [FOMC] main policy rate) was below -6% in October (Deutsche Bank, Bloomberg). That’s lower than at any point in the 1970s. By this measure, monetary policy is even more accommodative now than it was back then. And potentially even more dangerous.

This is the defining trait of the next inflationary era. Not double-digit inflation readings like the 1970s, but deeply negative real yields – mixed in with a sizeable dose of inflation volatility.

Originally published by ruffer.co.uk and reprinted here with permission.