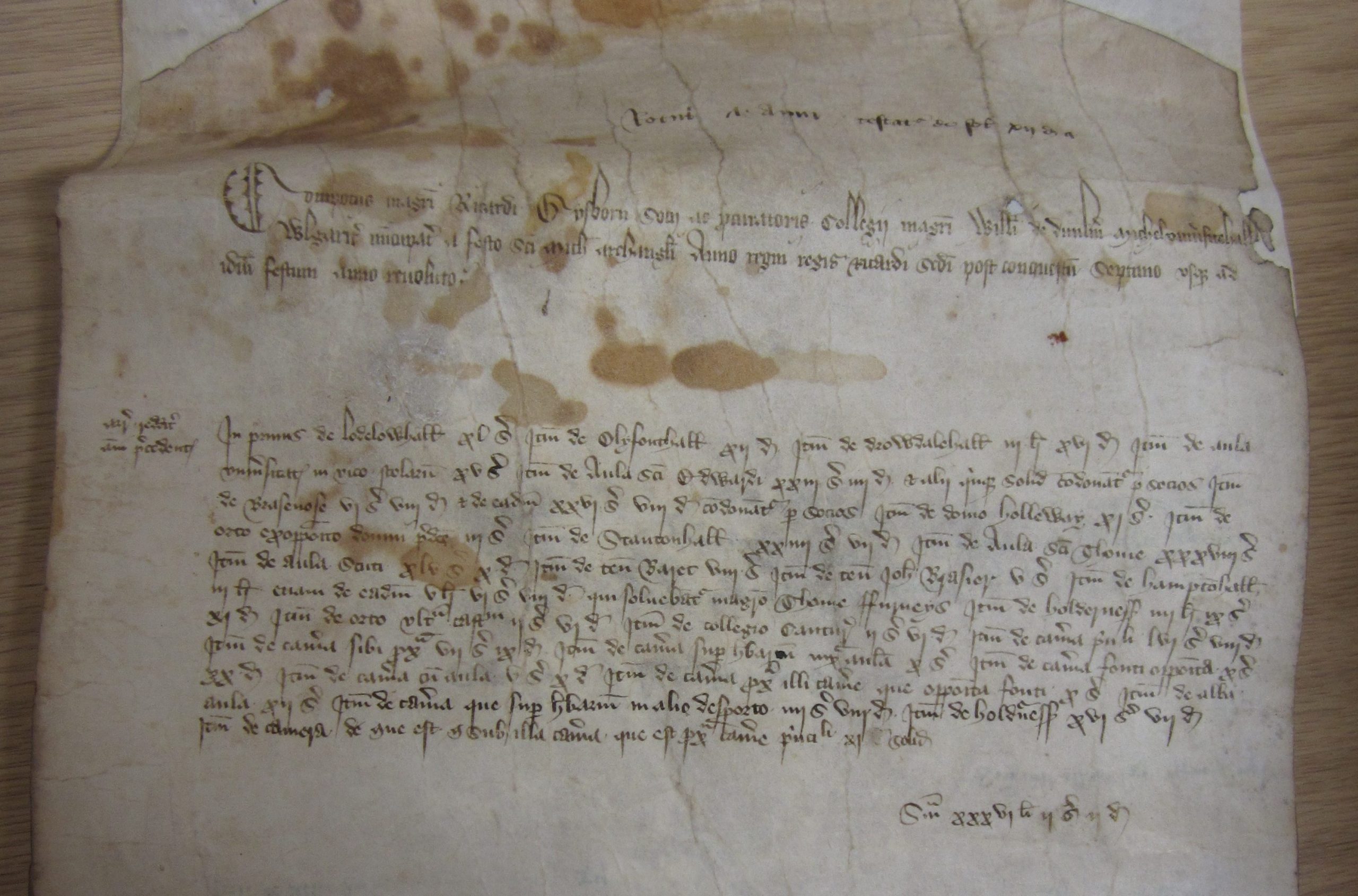

Above: The opening of the account roll of University College, Oxford, for 1383-4

© The Master and Fellows of University College, Oxford

ARTICLE ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED 21ST NOVEMBER 2017

Few organisations, apart from cathedrals, can rival Oxford and Cambridge colleges for the length and continuity of their existence: the first colleges in both universities were founded in the 13th century, and continue to this day. As a result, evidence for the oldest colleges’ property management can stretch back 600 or 700 years, and sometimes a college’s proof of title for a property may be a piece of medieval parchment: quaint and charming to look at, but possessing real legal weight.

In these three articles I will sketch how the colleges in Oxford have managed their property portfolios during this long time, starting off with the period before 1500.

We do not know when the University of Oxford was founded, but it was certainly in existence by the middle of the 12th century. But there were no colleges there: instead people lived in digs where they could. Even then, the earliest colleges, University, Balliol and Merton, were intended only for students who had completed their undergraduate degrees but wished to engage in postgraduate study, mainly in theology. Later foundations, such as New College and Magdalen, also offered scholarships for undergraduate scholars. Most medieval Oxford men (and Cambridge men, for that matter) would not have belonged to a college.

These colleges needed an endowment to give them a regular income, and in medieval times the only way to do this was to own land; investing money to yield a profit was forbidden by the Church. The more land a college owned, the greater its income, and the more fellows (the name given to its postgraduate students) it could subsidise.

Everything for a college depended on the wealth and longevity of one’s founder. The perfect founder was someone of great wealth (preferably a bishop or archbishop), who acquired a large collection of lands, made sure that their titles were secured, paid for new buildings, and then wrote a series of statutes. One such founder was William Waynflete, Bishop of Winchester, who founded Magdalen College in 1458. William lived for 30 more years, dying in his late 80s, assembling just such a collection of estates, creating the magnificent buildings which stand to this day, and drawing up statutes. As a result, Magdalen was in the 1480s the wealthiest college in Oxford, supporting 40 fellows, 30 scholars, and a chapel choir.

Not every college was so lucky. University College was founded thanks to a bequest from William of Durham, a theologian and cleric based in Sunderland who died in 1249. He left money to the University of Oxford to invest in land to support students of theology. The university managed to lose almost half of William’s bequest, and when statutes were drawn up for his college in 1280, the remaining funds could support just four fellows.

Of course somewhere like University College could appeal to benefactors for fresh endowments, and it was lucky: thanks to donations of land in Essex in 1403 and Yorkshire in 1443, its population had increased to about ten fellows by the 1450s. Further fundraising and hard work meant that by the 1450s it had also – at last – completed its first quadrangle.

It was one thing to own a property, quite another to manage it. Up until the later 20th century, the fellows of Oxford colleges took it in turn to act as bursar for a year (larger colleges had two or three bursars a year). One might worry about the possible effect of an amateur running one’s finances, but the term of office was just one year, to prevent too much disaster, and quite often a fellow who did have a good financial mind might serve as bursar more than once.

But bursars had to get on their horses and visit their properties. Wiser founders and benefactors might try to acquire properties for their colleges which were not too far away from Oxfordshire, extending, say, to Lincolnshire or Wiltshire. But poorer colleges depending on what a benefactor could give them might own estates in Yorkshire or Northumberland, a week’s ride away. This was not so bad if, as in the case of University College, most of its fellows came from from the north-east anyway. Evidence suggests that bursars didn’t visit their more far-flung properties every year.

However, there were times when external circumstances might cause trouble. The accounts for University College for the financial year starting in June 1460 show that its real income fell by half that year, before returning to normal in the following year. What was going on? The answer was that this financial year of 1460-1 saw the most brutal fighting in the Wars of the Roses. The fellows of University College decided that it would be unwise to visit any of their more distant properties – especially those in Yorkshire – and sat that year out in Oxford.

Civil war is something which today’s property manager, fortunately, does not have to contend with.