…and from place to place.

The third of a four-part mini-series written by economist Savvas Savouri.

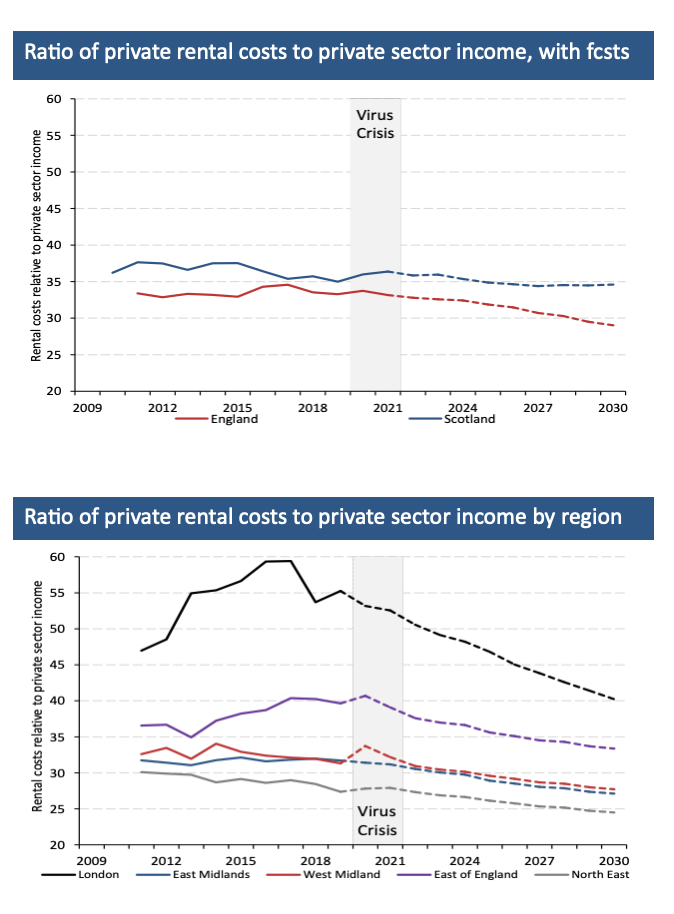

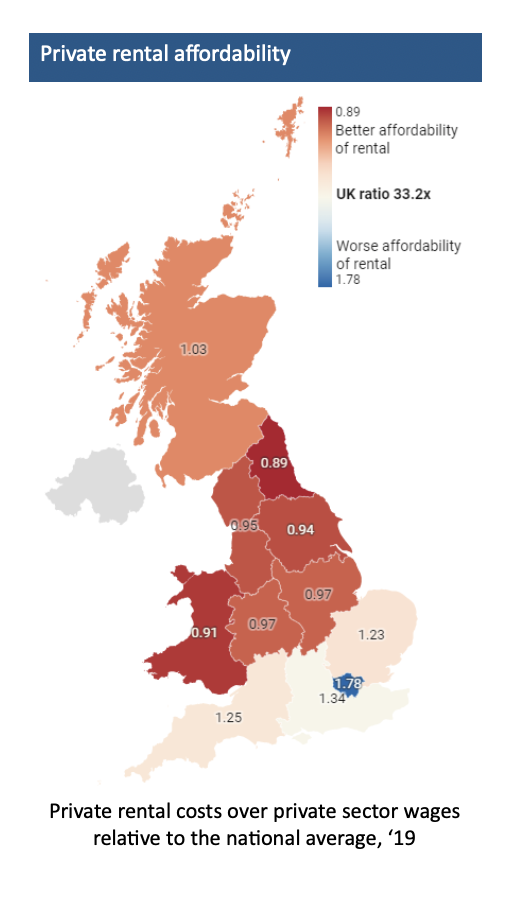

Housing matters are a crucial component in the composition of our regional outlook for the UK. One aspect is affordability and with this in mind, we assign positive weight to regions where the ratio of private sector rents to private sector incomes are comparatively lowest. We use the same reasoning – that there is a growth benefit to be derived from the affordability of rental housing – to positively weight regions which are home to the most affordable homes to own; as captured by a comparatively low ratio of regional house prices to private sector incomes.

By considering relative regional house prices, we argue that regions whose homes are comparatively cheap will enjoy a favourable degree of affordability arbitrage, and as a result, see net inwards movement. What we mean here is that we will very likely see homeowners in regions with comparatively high house prices ‘cashing-in’ to trade-up the property size and quality ladder (all the more the case if more affordable regions are close by to expensive ones).

As much as more affordable housing colours our ‘Regional growth future-ometer’ favourably, one cannot escape the fact that regions home to the greatest proportional residential wealth will also enjoy the spending multipliers that derive from this. We measure residential wealth by multiplying the average house price in each region by the number of homes that are owner occupied and rented privately within it. The assumption here, and a rather reasonable one at that, we believe, is that much of the UK’s stock of private rental housing is not only owned by individuals, but very much by those local. We divide this measure of regional private property wealth by regional population. And, to repeat, the underlying reasoning for including ‘housing wealth’ as giving colour to our ‘Regional growth future-ometer’ is its positive transmission into general private sector consumption and more general regional economic well-being.

We can see clear that owner-occupancy in Scotland is more ‘affordable’ – affordable relative to household incomes – than all but the North East of England. It is a different story, however, when one looks at regional rental costs relative to regional incomes. From this perspective Scotland is less affordable than anywhere across the UK outside of Southern England.

Bringing up the septet of housing factors we use to assess the UK’s regional economic outlook is a measure of total annual return from owning a home, captured by adding recent regional annual rental yield to annual capital growth. The idea is to gauge the degree to which regions best attract investment in housing. The development, that is, of new housing stock for private rent or ownership – the tenures we have made clear are deemed most accessible to those looking to work in a region. The simple logic here is that comparatively high total returns from residential housing should attract real estate investment capital. In terms of residential rental yields, Scotland scores higher than anywhere else across the UK.

All things being equal, the rental yield attraction should encourage private landlords to enter the market, and, by doing so, create more of what I claim is the form of tenure which makes for greatest ease of entry into a region. We need remember too that the private rental sector are where, for the most part, those studying full-time at university reside. The reality is that the existing momentum in build-to-rent will only accelerate but do so very much distinctly across the UK, with Scotland looking to be most laggard in this regard. For the issue is that private landlords have to compete with what in Scotland is the UK’s most sizeable proportion of ‘affordable’ public rental property. From the perspective of housing across the North East being more affordable, its border contiguity with Scotland cannot fail to see the exploitation of ‘migration arbitrage’ from one to the other; favourable to the North East, and to Scotland’s cost.

Comparatively high total returns on housing are only possible of course because yields are themselves comparatively high, or house price inflation is. And, if house price inflation is comparatively high, our reasoning is that this will make home ownership less affordable. Similarly, if rental yields are comparatively high, then so, ceteris paribus, will private sector rents – making private rental less affordable. Not only are all these cross-currents undeniable, they sit well within our ‘Regional growth future-ometer’.