…and from place to place

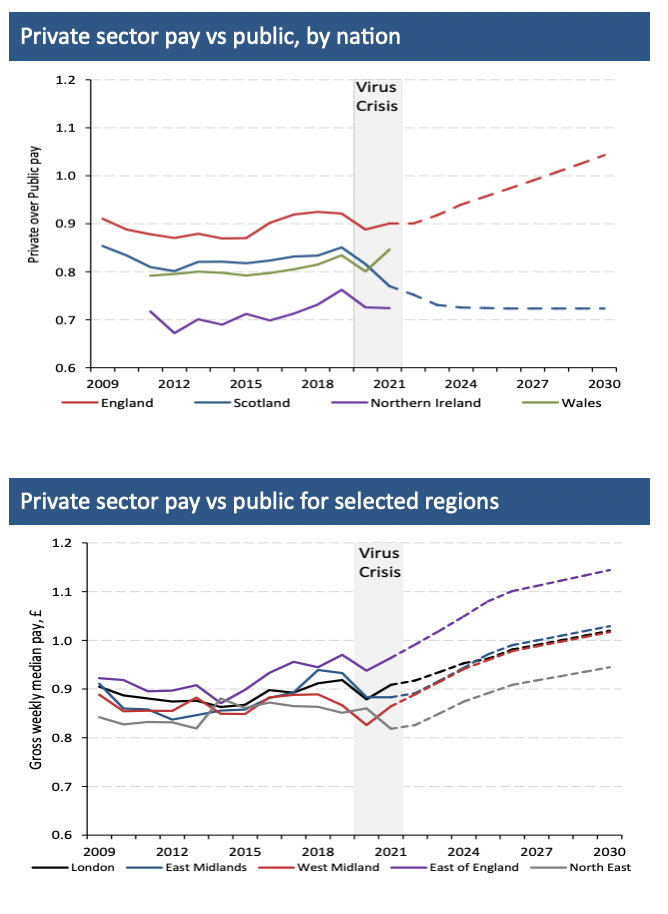

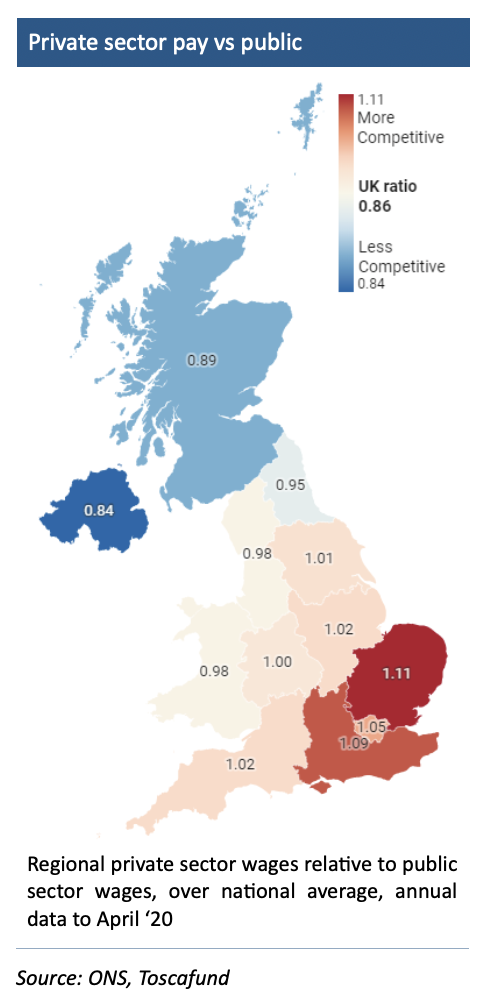

Our forecasts offer an economic outlook for the UK in terms of both time, out to 2030, and space, across its 12 regions. Among factors we consider are spatial differences in employment shares by sector, housing tenures and the affordability of both private rental and home ownership. Included too is the pay competitiveness of labour between public and private sectors. Regional wages appear is in terms of the ratio between the private and public sectors. The argument here is that regions where this ratio is higher than the national average will fare better in business growth thanks to the public sector crowding out the private sector less. Weight was also given to how well represented a region is by private enterprise, and how welcoming and appealing regions appear to be towards high fee-paying students from overseas. Room is given to regional ‘gravitational pull’, the lure for workers, both those within the UK and those looking to come here from overseas.

By collecting together the 31 separate and specific elements which are baked into the ‘Regional growth future-ometer’, we assert that over the coming years, the regions of Central and Northern England (CaNE) will very likely most impressively top UK growth league tables. In identifying CaNE as a standout this should in no way be considered a slight on economic prospects elsewhere within the UK, as the UK economy in aggregate will grow ahead of expectations.

At the core of our argument is how certain regions happen to be favoured by their core positioning. Specifically, CaNE sits comfortably such that it has a near 360 degree radial connectivity in logistical terms to other parts of the UK. CaNE is also favoured because it is well-positioned to capitalise in the years ahead on the certain reshoring of productive capacity and shortening of supply-chains; moves driven by economic and environmental motives. With the UK also sure to see inventory management within it altered from just-in-time to just-in-case – requiring greater warehousing capacity – here too CaNE sits pretty well.

Further, while HEI’s are spread far and wide across the UK, CaNE boasts a particularly high concentration of them. And since the UK’s universities are certain to benefit from the growth in generous fee-paying students arriving from overseas – most notably the growth behemoth that is China – CaNE will benefit strongly in this regard. CaNE also enjoys fortuitous topography and a plentiful availability of development land to create all manner of new work and living space. Indeed, a comparatively high population density, and motorway (and wider transport) networks, make CaNE enabled in many positive economic ways. Regarding UK manufacturing, CaNE’s existing industrial capacity is strong, not least in auto and aero engineering plants, both set to enjoy significant clean engine re-tooling. Real time regional vacancy data illustrates what lies ahead, with CaNE seeing extremely strongest hiring intentions.

Just a casual glance at where Scotland sits shows how its topography and population density places it poorly to capture the surge in e-commerce which has taken considerable post-pandemic hold across CaNE, and taken up considerable space and staff in the process. Regarding manufacturing, Scotland scores worse in existing industrial capacity when compared to CaNE, particularly in auto and aero sectors. Let me turn to Scotland’s impressive higher education institutions. Here too, Scotland stands out unfavourably.

The reality is that with Scottish students subsidised in their home universities, they ‘crowd-out’ others – notably the Chinese – who would otherwise pay far more generously for their study and accommodation; Scotland consequently missing the wider economic engagement with these third party nationals during and after study. Moreover, the finance needed to add new higher education capacity is reduced with fee income constrained by the generosity to home students. Scotland can of course boast comparatively strong job creation across its public/quasi-public sectors; sectors whose foremost customer is the Scottish Government and its affiliates. It cannot however make a similar claim for sectors unlinked to The State. As a result, Scots graduating from home universities and seeking to work across the private sector are likely to take themselves south, where both public and private sector work is more plentiful and pay is more generous. Holyrood can be accused, in fact, of feeding England’s appetite for graduates, via a subsidy. What of new housing construction and the proportionate share and creation of entirely new private rental stock? These important metrics for labour mobility also see Scotland score poorly; its comparatively large share of social housing discouraging the development of privately-rented stock. As much as Scotland has a 96 mile border with CaNE, it is conjoint with CaNE’s very northern hinterlands. By contrast, Wales and England’s south touch CaNE’s heartlands. Neighbours however, which despite working alongside, they will lag behind, albeit not as far away as Scotland.