Christopher Cole of Artemis Capital Management in Texas, published a research article in July entitled, What is water in the markets?, which has resonated powerfully with the investment community and performed a valuable service in identifying the inherent dangers of passive investing. Cole asserts that the most obvious, ubiquitous, important realities are often the ones that are the hardest to see and discuss. His title came from an apocryphal tale, summarised in Figure 1. His essay foretells a coming volatility storm in which confidence in the entire medium of modern credit creation and the formation of asset prices, from which all measures of financial wealth are derived, is shaken.

Figure 1.

The essay spans liquidity, volatility, and passive investing, challenging conventional wisdom at multiple points along the way. He posits a shift in the dominant view from believing that value is independent of the medium and intrinsic to the asset, to believing that the medium (liquidity) is the sole determinant of value, as defined by continuous bid and ask prices. If an asset is only worth what someone is willing to pay for it, and value is ‘created’ by the medium of money, then there is no need to pay someone to find value through active investment management.

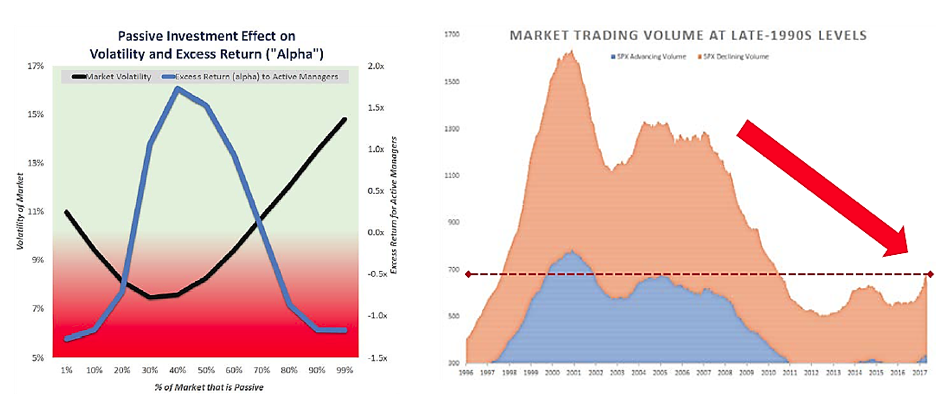

Figure 2. Data source: Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Hence the triumph of passive investing. Value investing has now had the longest period of underperformance in history when compared to buying whatever is ‘hot’, illustrated for the U.S. in Figure 2. The U.S. has reached a tipping point, according to Bernstein Research, when more than half of the assets under management will be passively managed. JP Morgan suggests that only 10% of trading volume in stocks comes from discretionary trading. Cole maintains that passive investing is just a crowded liquidity momentum trade and its outperformance compared to active managers may become self-fulfilling and ultimately de-stabilising in the long-run. When passive investing becomes dominant, excess returns diminish and volatility tends to rise.

Cole’s model simulation work finds that the excess returns available to active fund managers is highest when 42% of the market is passive, but as the concentration exceeds 60%, the model (Figure 3, left frame) becomes increasingly unstable and subject to wild trends, extreme volatility and negative alpha. He reckons that in real life the upper threshold would be lower than 60%. Cole contends that the volatility (VIX) spike in February was not a volatility event, but a liquidity event. Traders were not buying options because they thought that volatility would increase, they were buying options because they were facing insolvency.

Figure 3. Source: Artemis Capital Management

The bull market in the S&P 500 index is now the second longest and has the second largest value gain in history, but it is the only bull-market that has occurred on lower and lower trading volumes. Market trading volume and free-float shares are now at levels last seen in the late 1990s (Figure 3, right frame). As terrible as the liquidity was in February, it did not happen in the context of a fundamentally-driven market crash. Cole argues that the U.S. tax cut might be enough to offset the negative effects of Quantitative Tightening for a while, but that a crunch is coming.

Capital repatriated to the U.S. in the aftermath of the last federal budget has been widely reported as flowing into share buybacks among other uses. Cole suggests that this acts as a price insensitive buyer underpinning the equity market, dampening volatility and encouraging additional buying pressure from implicit short volatility strategies. He concludes that a crisis-level drought in liquidity will arrive between 2019 to 2022, marked by a perfect dust storm of unprecedented debt supply, quantitative tightening and demographic outflows.

The article highlights that one of the effects of quantitative easing has been to damage the relationship between the corporate debt expansion and its default rate. This will become a problem as indebted corporations try to refinance when the markets are most vulnerable to a liquidity drought. This is the terrible price to be paid for assuming that there will always be willing buyers and sellers, in size, allowing the smooth entry and exit from individual stocks and funds.

A version of this article also appear in the Halkin Letter.