Uncompromising in his vision, architect Peter Zumthor faces his toughest challenge to date

Not long after his celebrated thermal baths were completed, Peter Zumthor, a reclusive Swiss architect, gave a rare lecture at the Royal Institute of British Architects. Everyone was eager to see details of the minimalist’s work and hear what he had to say. The lecture hall was packed to the brim, with barely standing room in the aisles; everyone waited in anticipation.

Peter Zumthor walked onto the stage to rapturous applause. Behind the lectern a large yellow monochrome rectangle was projected onto a giant screen. “Tonight,” the great man announced, “I will … read to you my Beat poetry. Accompanying each poem will be a colour slide that particularly connects to the poem that I will read”. As it became apparent that this was not some sort of elaborate joke, there was an overwhelming sense of bemusement which gradually turned to disappointment as Zumthor launched into one verse of obscure poetry after another. Zumthor was no Jack Kerouac, and gradually the audience drifted away.

Zumthor is a tough architect to like. His reputation as a reclusive, mountain-dwelling hermit is, he admits, hard to eliminate. He rarely publishes his work. He would rather people visit his buildings than look at pictures of them in books. His studio is in the very remote location of Haldenstein, an obscure valley in the south-east of Switzerland. He is notorious for vetting clients and making them wait. He has shunned interviews in the past and has no website. He prefers to summon journalists to his mountain retreat, which also contributes to the myth. He is an architect’s architect – but he even tests those architects who admire his work. He is a purist and expects everyone else to be too.

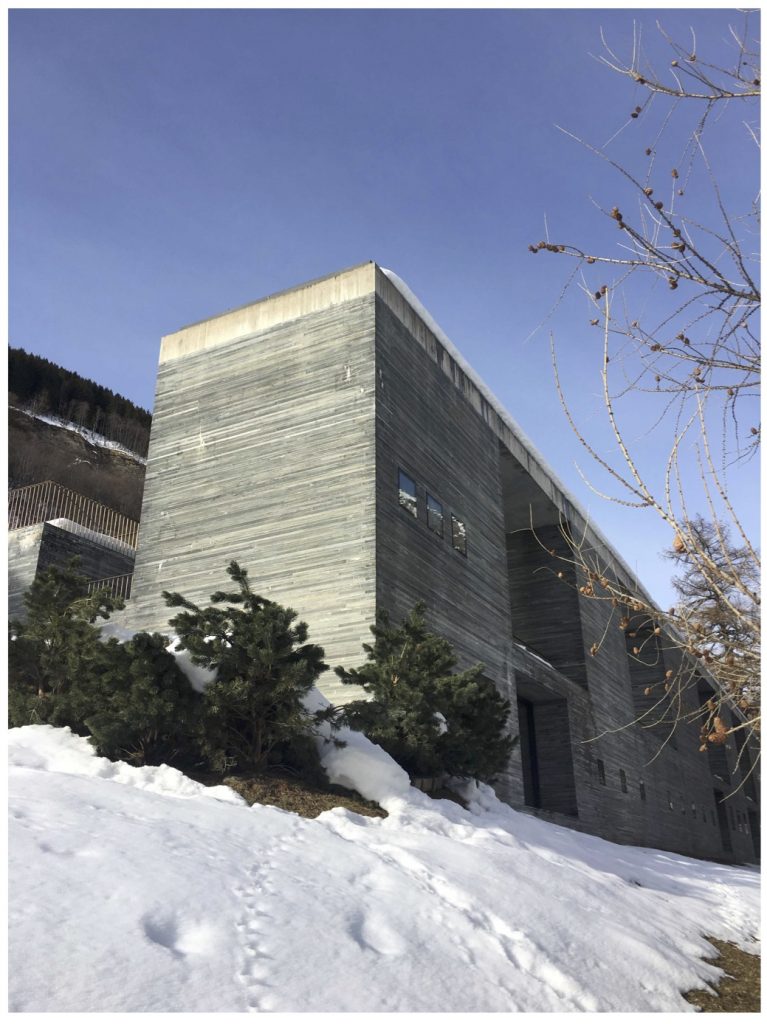

Thermal Baths at Vals by Peter Zumthor Exterior view top and interior view bottom (Photographs by author)

It is a dream of many architects to build a building in one material only. With his thermal baths at Vals, Switzerland, Zumthor has almost achieved it. Vals is a small village, with naturally occurring hot springs, in Graubunden (one of the 26 cantons in Switzerland) about two hours’ drive south-east of Zurich. The baths are monolithic and made from layers of the local gneiss stone, quarried a kilometer up the valley. The building seems to rise naturally out of the ground in the forest. Both the material and the design play with the hot water, the reflections and the steam-filled air. But there is nothing compromising about this building. Even the spaces inside are built of this hard grey stone in a sort of geometric cave system. The program for the baths is uncompromising too. Each successive room dwells on one particular sense. One room is for touch, one for smell, another for sound etc. If one talks, which is strictly forbidden, an assistant appears out of nowhere to remind one that one is not allowed to speak. Relaxation takes hard work and concentration please – these are the rules.

This building, however, like most of Zumthor’s work is extremely poetic, even moving. But how does he achieve this effect? Zumthor has said in interviews that his design process starts with a feeling or a sense that comes from his intuition. Once he has grasped that intuitive sense, he fiercely holds on to it and is uncompromising in achieving his vision. He says, “I take care that nobody destroys my first image”. As anyone who has commissioned a building knows, there are many things that can derail the initial building concept. Rising costs, interfering clients, difficult permissions, often mundane practicalities like servicing and structure, onerous health and safety requirements, litigious contractors – all of these things can push a building far away from the initial vision. Zumthor seems to have a gift for having that vision, communicating that vision and then expressing it in built form. This uncompromising attitude has, no doubt, ended in some failures, but has resulted in his built works being, in my opinion, highly successful, even beautiful.

Beautiful is a word that is deeply unfashionable in the visual arts today. Often architects and artists feel ashamed to use it. It sounds unsophisticated, even naïve – and what does it mean anyway? It also precludes the ability to be ironic, a trait that is now highly valued throughout the world of visual arts. In this instance, Zumthor is unusual in that he is honest enough to believe in beauty and to even strive for it. He believes that buildings should be beautiful and I would agree with him that all the buildings of his that I have seen are indeed deeply moving. They have a directness and a refinement that is supremely elegant and, yes, even beautiful.

So how does Zumthor achieve this? Part of the answer lies in his emphasis on materials. He says, “it is about how they are; it is about what presence they develop”. Equally, that “architecture is not so much about form, it is about materials”. A second part of the answer lies in construction; Zumthor believes that the method of construction should come out of the material used. Indeed, he is extremely poetic about materials and has a natural sympathy for how they should be put together. He abhors the normal state of affairs in a building where the structure is invisible and the finishes are hung off the structure. For him, the method of construction should be informed by the materials used. This gives his buildings clarity, a directness that is easy to understand and a seeming simplicity that is very human because it is so instantly legible.

Thirdly, Zumthor talks about atmosphere; a harder concept to grasp. In lectures and interviews, he has tried to explain what he means by atmosphere. He says that “architecture is experienced by laymen without thinking”. He says, “we must let go of cerebral or academic things and trust intuition”. It seems that his designs start with the idea of expressing a feeling, a sense or an atmosphere; he holds onto this idea, passing through his great respect for material; which then informs the method of construction until, at the end, the building has a form and a soul. He says that “there is no difference between the two sentences – the building is beautiful and the building has soul.”

Where did Zumthor get this rather uncompromising architectural method and poetic view of the world? Part of the answer to that question can be found in the town of Chur, the regional capital of Graubunden, the canton where Zumthor grew up. Zumthor is a great admirer of an obscure brutalist church built in this small city. Brutalism is a style of architecture that is deeply disliked by most at present, especially in Britain. Attempts have been made, by Elaine Harwood, for example, in her rather dry book ‘Space, Hope and Brutalism’, to rehabilitate this expressive period in architecture, but without much success. It seems that the raw, sculptural qualities of brutalism are just not yet appreciated, in this country at least. But, for Zumthor, the uncompromising rawness of the Heiligkreuzkirche by Walter Forderer is an inspiration.

Heiligkreuzkirche by Walter Forderer Exterior view top and interior view bottom (Photographs by author)

This church, on the outskirts of Chur, is built almost solely from reinforced concrete, both inside and out. The windows are so recessed that they seem not to exist at all. The sculptural quality of poured concrete is explored in an orgy of geometric forms. What results is almost pure sculpture rather than building. There are occasional moments when wood is used, for the seating in the interior, for example, but this is rare. It is a sort of monolithic, expressive riot of orthogonal and octagonal form that seems to have inspired Zumthor greatly.

Zumthor gained great acclaim for his building at Vals, which drew the attention of the wider world, but by then he had already built a number of gems. The St Benedict chapel, designed in 1988, is one of them, as it perfectly encapsulates the spiritual qualities of his work. This tiny chapel, again seemingly built of one material (wood), is situated on the high slopes above the charming and ancient village of Sumvitg. This clear and direct structure is designed in plan in the shape of a tear drop. The clerestory lighting is both inspiring and contemplative in the way all church lighting should be, but rarely is. The purity of the timber construction is expressed superbly and elegantly in the herringbone structure of the roof. This is a place which really inspires a moment of quiet thoughtful prayer, a welcome moment of peace in a fraught, busy world. Despite the buildings small size, it’s impact, especially internally, is immense: it is very small, yet a masterpiece.

Since the thermal baths at Vals, Zumthor has built successfully in Brigenz, Austria, where he designed the Kunsthall in 1997 on the shores of Lake Constance. In 2007, he completed the Kolomba Diocesan Museum in Cologne, and designed the Bruder Klaus Chapel in a field on a farm near Wachendorf, both in Germany. In 2011, he collaborated with the artist Louise Bourgeois to design a memorial for the victims of the witch trials in Varanger, Norway. In Britain, he designed the temporary Serpentine Pavilion in London in 2011, but has recently turned down the opportunity to build a new library for Magdalen College, Oxford. Zumthor has also recently completed a secular retreat in Devon for Living Architecture; this project, set up by public philosopher Alain de Botton, commissions and builds holiday houses by leading contemporary architects for paying guests. This is not a huge repertoire for an architect who was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2009 and the RIBA Gold Medal in 2013. Not long after receiving the Gold Medal, he was picked out of relative obscurity to design the new Los Angeles County Museum of Art building in Los Angeles, California.

St Benedict chapel at Sumvitg by Peter Zumthor Exterior view top and interior view bottom (Photographs by author)

Zumthor has proposed a sort of black, abstract, Jean Arp shaped form that is inspired by the La Brea tar pits that exist on part of the site. Other architects have failed here, most notably Rem Koolhaas, whose 2001 competition winning proposal was never built. Zumthor’s design is controversial. It requires a huge amount of money to be raised and it also proposes demolishing three existing buildings on the site. These buildings were built by families who donated large sums of money and important artworks to the collection and so some of their descendants are, understandably, unhappy about the proposal. The choice of Zumthor was a daring and totally unexpected choice, and I suspect that Michael Govan, director of LACMA and a huge fan of Zumthor, was very influential in that choice.

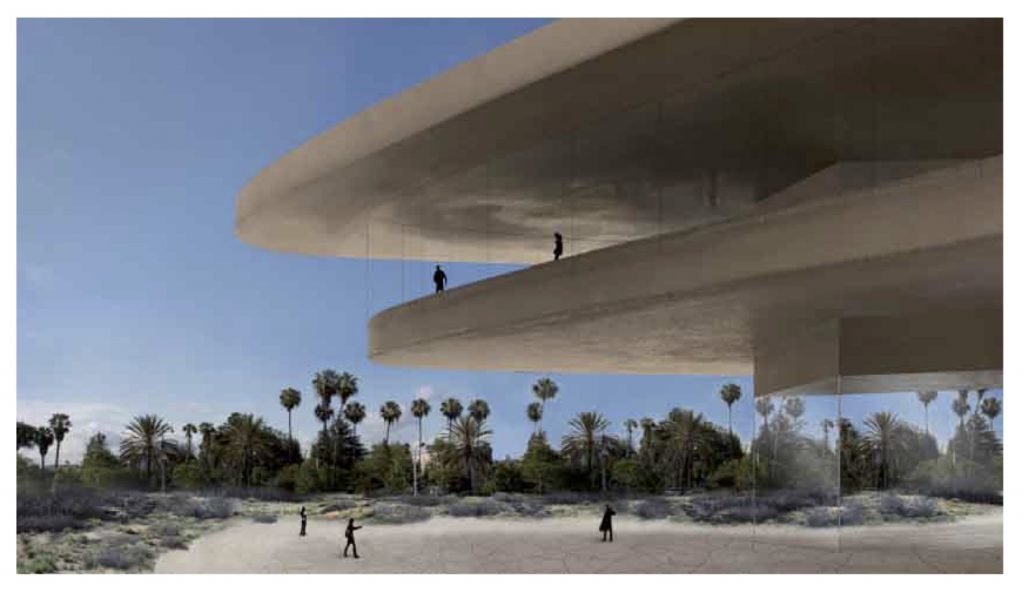

Image of model of original winning design for LACMA by Peter Zumthor

The original design, which resembles a splash of black tar, was exciting but immediately faced resistance. First of all, it was alleged that Zumthor had not visited the site before he designed the building, rumours which have never been fully denied. Secondly, Zumthor was asked to change the design because the proposed building encroached on the fossil rich and popular La Brea tar pits, part of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. The new proposal now spans Wilshire Boulevard but, instead of glossy black, it may now be clad in travertine stone, seemingly at odds with its original, organic shape.

This is undoubtedly Zumthor’s greatest challenge so far; not only because the scale of the building is greater than anything he has done before, but because the potential obstacles are greater. Assuming that all the money is finally raised (and rumours are that the target has been achieved), it will be interesting to see if Zumthor holds onto his original vision. As projects get bigger and become more public, they have a wider, more varied, ownership and consequently face greater challenges. We have already seen that Zumthor has been asked to change his design and amend the proposed material for the new museum. But let us hope that his intentions do not get watered down too much, or, even worse, blocked. This would be a great loss for Los Angeles. LACMA have made a brave choice and, having made that choice, they will have to trust in Zumthor to deliver the beautiful, poetic building that I know he is capable of. Let’s hope that they do trust him and that he does deliver. Or maybe (and we know he has past form on this) he will take us all by surprise.

Image of model of revised design for LACMA by Peter Zumthor