As the global economy slips into the deep pit of despair, many market commentators are crying out for global central banks to wake-up and save the day. While many are intensely commenting on policymakers in Washington and the Global Trade Uncertainty – underneath the surface a powerful market-driven force has already started to offset the effects of a real downturn.

Deterioration in Global economic growth and inflation expectations has pushed U.S. long-term rates to new lows. The changes in long-term interest rates are providing the real financial incentives necessary to refinance past mortgage debts. Depending on how far 30-yr mortgage rates fall, the amount refinanced has the potential to provide an economic stimulus upwards of 200 billion dollars. This stimulus will come in the form of residential investment and personal consumption.

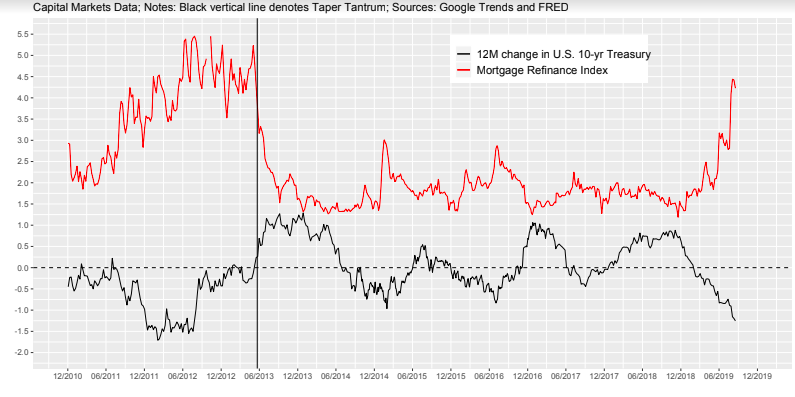

Dormant for six years (the last great wave ended abruptly with the Taper Tantrum) mortgage refi’s are now starting to show real momentum. According to Leonard Kieferof Freddie Mac, an estimated 4 trillion in unpaid mortgage balances came “into the money” when the 30-yr fixed rate mortgage rate broke-through 4% on May 30th. Although it is common to refer to the level of mortgage rates (as Leonard did), the ‘cyclical’ offsetting macro push comes from changes in rates, and more specifically, at the annual horizon. This serves as the largely underrated link that mortgages play in offsetting economic downturns. The figure below plots the weekly mortgage refi index based on 49 Google search trends against the annual change in the 10-yr Treasury rate.

The concept of capital market issuance leading the charge towards recovery was first seriously explored by Leonard Ayres (1939)[1]. Ayres’ focus was on corporate issuance leading business fixed investment. Today, it is mortgage issuance leading the charge through increased consumption and residential investment from interest savings. As some coastal residential markets have recently exhibited signs of weakness – this interest rate savings could offset some of the negative effects soft housing markets tend to have on home owner consumption.

I’ve coined the term “Quantity-Expectations Parity” (QEP) to describe the process through which feedback loops between financial prices and the real economy occur. QEP states that incentives matter. If income is lower today than it was a year ago, then households have the economic incentives to raise cash to meet this income shortfall. Incentives are also created by changing financial prices. This is what we are currently experiencing: lower interest rates today than that seen one-year ago have created the financial incentive to refinance.

Economic and financial incentives amplify each other. In fact, research has shown that liquidity-constrained households spend a large share of the money saved from refinancing. For example, Erik Hurst and Frank Stafford estimated that those experiencing an unemployment shock were 25% more likely to refinance from 1991-1994 and that, “Liquidity-constrained households converted over two-thirds of every dollar of equity they removed into current consumption … producing an estimated expenditure stimulus of at least $28 billion.”[2]

A simple back-of-the-envelope calculation reveals that some 90 billion dollars (5% of GDP) in saved interest and principal could be recycled back into the U.S. economy. If mortgage rates fall to 3% this figure could balloon to 223 billion dollars, or 12.5% of GDP. Depending on how far long-term interest rates fall, the prepayment option may provide a delightfully large and unexpected stimulus to U.S. growth. Without Ashes, There Can Be No Phoenix.

[1]Ayres, Leonard Porter. “Turning points in business cycles.” (1939).

[2]Hurst, E., & Stafford, F. (2004). Home Is Where the Equity Is: Mortgage Refinancing and Household Consumption. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 36(6), 985-1014. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3839098