Rising populism threatens to end institutional SFR as we know it. What happens next and who are the likely winners and losers?

Single-family rentals have been one of the fastest-growing real estate sectors of the past decade. But political pressure is putting the future of the category in jeopardy.

Over the past year, a series of bills have been introduced that would seriously restrict institutional investors’ ability to buy single-family homes. While the particular federal legislation introduced is unlikely to pass in this Congress, rising populism as well as frustration with home prices on both sides of the aisle raise the probability that something will happen sooner rather than later—through individual state legislatures if not at the federal level. And unlike the multifamily or office sectors, SFR doesn’t have an established lobbying presence or organizing power to fight back.

Today’s letter will explore the implications of a possible crackdown on Wall Street involvement in buying and renting single-family homes. Specifically, we’ll tackle:

- The potential contours of new regulation;

- Models and businesses facing threats from a pending crackdown;

- Proptech companies and investment sectors that may benefit;

- Macro impact on the single-family sector.

The Shape of Regulation

Before we predict winners and losers, it’s worth taking a look at the actual legislation that has been put on the table. After all, slight differences in a law’s scope can lead to very different outcomes for the industry. While it’s impossible to predict how regulation might take shape, we can use the text of proposed laws to do some informed speculation and predict how government intervention into the single-family market may develop.

At the federal level, two anti-SFR laws have been introduced:

- S.3402: End Hedge Fund Control of American Homes Act

This proposed law prohibits any investor from owning more than 100 single-family homes. Any investors with more than 100 homes must sell 10% of their inventory per year to individual buyers (not other investors) or face an excise tax of $20,000 per year per home over 100.

In this bill, “ownership” is defined as “majority interest,” an important distinction as we consider some of the consequences of these laws.

- S.2224: Stop Predatory Investing Act

This proposed law targets investors that own more than 50 single-family homes, prohibiting them from taking any tax deductions for mortgage interest or depreciation on the single-family homes they own.

Notably, this bill excludes LIHTC-financed single-family homes as well as build-to-rent developments. And unlike S.3402, it would only apply to homes purchased after the date of enactment, so investors would not be forced to offload their portfolios.

Efforts are also being made at the state level to curb investor ownership of homes. While no bill has yet passed, the shape of these proposed laws is informative:

- California AB2584: This bill is quite simple—it would ban investors that own more than 1,000 single-family homes from buying any more.

- California AB1333: AB1333 is basically the inverse of AB2584; it prohibits a homebuilder from selling a new single-family home to an institutional investor, which is defined as an entity owning more than 1,000 single-family homes.

- Nebraska: A bill was introduced which proposes to ban “corporations, hedge funds, and other businesses” from buying single-family homes unless the business “and its principal members” live in Nebraska. The Warren Buffett carveout, if you will.

- North Carolina: A complex bit of regulation was proposed last year which would prohibit “any single entity” from “owning more than 100 homes in counties with over 150,000 people.” North Carolina has 21 counties which qualify, and no exemption was made for build-to-rent.

- Minnesota: A proposal is currently working its way through the legislature that would ban “corporations, limited liability companies and investment funds” from “purchasing and renting more than 10 single-family homes.” The law carves out “non-profits, builders, and small family-owned LLCs,” so it should exempt most build-to-rent. Any violators would be forced to divest within a year.

While the Nebraska and North Carolina bills seem very unlikely to move forward, I wouldn’t be surprised to see the Minnesota law and some version of the California proposals come to pass. And we’re certainly going to see new proposals and more momentum around these ideas in 2025’s legislative sessions.

Before we move along, I should make it clear that I don’t believe any of these regulations will help make homes more affordable for buyers, but they will hurt renters and upward mobility in the US. Institutional investors compose a tiny percentage of all single-family home purchases, and single-family rentals are a path for working-class families to access good school districts otherwise locked behind a steep down payment barrier to entry.

But if a crackdown does come—and at this point, I believe it’s more likely than not—it’s worth looking at the winners and losers.

Platforms Under Threat

Assuming the legislation is crafted reasonably well—hardly a guarantee, I know—the obvious loser here will be investment firms that buy single-family homes. This includes Invitation Homes, Tricon, Pretium, and many more.

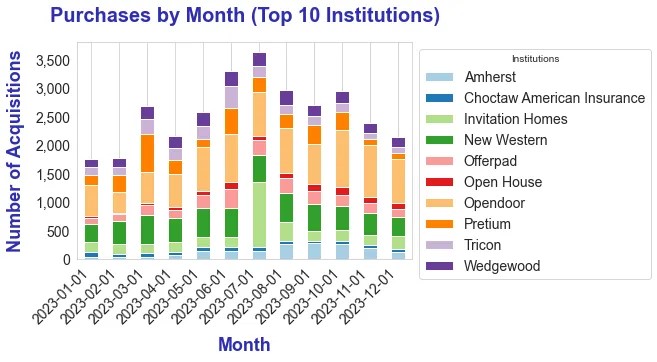

In addition to hitting traditional real estate investors, any legislation would likely impact tech platforms that buy single-family homes—such as Offerpad and Opendoor—as well. Any federal legislation on this topic would effectively put them all under, assuming they aren’t already out of business by that point.

Proposed legislation varies on the requirement for investors to offload existing single-family portfolios. The most recent proposed federal legislation (S.3402) does, while some proposed laws at the state level avoid a divestment requirement citing the mass displacement of single-family tenants that would result.

If investors are compelled to offload their portfolios, they’ll be doing so as forced sellers at the same time as all other institutional SFR investors, likely pushing a glut of inventory onto the market. So while investment managers like Blackstone will suffer lost fee streams, their backers—retail investors in REITs as well as pension and insurance funds—will take the biggest financial hit.

Companies that serve institutional single-family owners will also see their businesses suffer. AppFolio, for example, is the property management system of choice for institutional SFR owners. Companies like Entera and Roofstock are likely in jeopardy as well, particularly if the bar for “institutional owner” is set low—e.g., at Minnesota’s 10 rather than California’s 1,000.

Sale-leaseback and Rent-to-own models are also likely to get caught up in any legislation, as their business models are predicated on owning homes outright for some period of time. No proposed legislation has included exemptions for these businesses or any “temporary” institutional ownership of homes. Home Partners of America, Divvy, EasyKnock, and Truehold are a handful of the companies at risk.

But the greatest tragedy here would be if a prohibition on institutional single-family ownership ended the growing build-to-rent sector. Build-to-rent—in which developers purpose-build single-family homes for the purposes of renting them out long-term—is gaining serious traction in the United States, with an estimated 97,000 BTR units completed in 2023.

While some legislation exempts BTR, other proposed laws do not. Notably, only one of the two proposed federal laws prohibiting institutional ownership of homes excludes “build-for-rent developments.” It’s important to distinguish this from Minnesota’s proposed law, which carves out “builders”—possibly implying that BTR developers are only excluded from the law insofar as they hold, rather than sell, their projects.

Beneficiaries and Emerging Models

But as with any change, there will be winners too. Of course, the models and companies that ultimately benefit will depend on the text of the specific laws that actually get passed.

The Mom-and-Pop Ecosystem

The crackdown on institutional SFR owners won’t stop SFR demand. Instead, it will move the center of gravity of SFR ownership to smaller owners, including mom-and-pops and small, local home rental operations.

Facing less competition, these owners stand to benefit. Some small SFR operators may choose to raise limited amounts of outside capital, and capital allocators may emerge to distribute large, institutional checks across multiple small operators while keeping each below the legally-mandated ownership cap. Of course, new laws may emerge to limit this workaround, creating a cat-and-mouse game between investors and regulators.

Regardless, companies that serve mom-and pop SFR owners stand to benefit. SFR property management companies—which typically serve small-to-midsize owners without in-house management—will rise with the tide alongside their clients. While a SFR owner with 20,000 units will probably have in-house management, a smaller operator with 10 or 100 units is far more likely to partner with a Mynd (now part of Roofstock) or ZipRent.

Lenders that serve small SFR operators and house flippers, such as Roc Capital, are also likely to benefit a shift toward smaller SFR operators.

However, these proposed laws have a downside for mom-and-pop owners: while mom-and-pop single-family landlords may face less competition from institutional owners, they’ll also lose a path to exit their portfolios—an increasingly relevant point given that many mom-and-pop owners are aging. Companies like Flock Homes—which allow small owners to do a 721 exchange, trading their portfolios for REIT shares—might not be legal under new rules.

HEI and Fractional Models

Other than S.3402, which defines ownership as “majority interest,” most of the proposed laws are silent on the meaning of “ownership” of a single-family home. As regular Thesis Driven readers will know, lots of new models have emerged in recent years to help people buy homes—and many of them challenge the traditional concept of ownership along the way.

Take Point, for example. Point makes home equity investments (HEIs) in existing single-family homes, effectively buying a “share” of a home’s appreciation from the owner. But the owner stays on the title and Point typically only buys a minority—15% to 20% is typical—stake. By the terms of S.3402, at least, Point is in the clear. (EasyKnock’s HomePace and Unison are other players in the HEI space.)

Depending on the contours of the law, legislation could provide a massive tailwind for these companies. Exposure to the single-family market will still be an in-demand product among investors. And when it wants exposure, capital tends to find a way to get exposure. Unless legislation bans any investor ownership—even minority stakes—HEI, co-investment, and fractional ownership models are likely to be big winners here, and companies may quickly find themselves with more real estate capital than they’re able to deploy given that many of them have high-touch screening, sales, and onboarding processes and small check sizes.

But depending on their models, other “shared ownership” companies may be more vulnerable. Ownify, which we profiled on Thesis Driven earlier this summer, begins with a significant majority ownership share of its homes, with home buyers earning a stake over time. While Ownify’s model lowers the barrier to homeownership, it likely conflicts with most proposed laws targeting institutional investors.

Demand for single-family rentals isn’t going away.

This article was originally published in the Thesis Driven and is republished here with permission.

Americans will still seek out nice homes with yards in good school districts. If they can’t afford a down payment—or don’t want to commit to owning a specific home long-term—they’ll look to rent. If the law prohibits them from renting from an institutional owner, they’ll look to rent from someone else.

And investors will still look for exposure to the single-family market. If they can’t achieve that through vehicles like Invitation Homes and other large operators, they’ll do so through HEI and co-investment products, BTR communities, or more widely distributed allocations amongst smaller managers.

Regulation will, however, shake up the way the market works today and likely cause headaches for renters and investors alike. For everyone’s sake, I hope legislators stand off and let the market work.

This article was originally published in the Thesis Driven and is republished here with permission.