Implications for real assets demand.

The repercussions of Covid-19 will continue to be felt long after the final phases of the pandemic are over. Assumptions that are underpinned by real assets secular demand drivers require revising.

At CBRE Investment Management, we describe ourselves as structurally driven investors. Simply put, we look for long-run structural changes in how our customers use the built environment and try to create the real assets that meet that evolving demand. This approach has underpinned our outsized allocations to emerging property asset classes, including student housing, senior living and life sciences. Our House View reflected our belief that demographic trends would drive demand for under-supplied real estate formats and deliver superior returns.

In this new series, we unpick the hidden demographic pivot points of the last two years and assess how our demographic assumptions might require re-evaluation. We will outline whether our re-analysis of demographic trends change to materially impact real assets forecasts over the next four decades across the major core markets where we invest – the US, UK, eurozone, Japan, Australia and China.

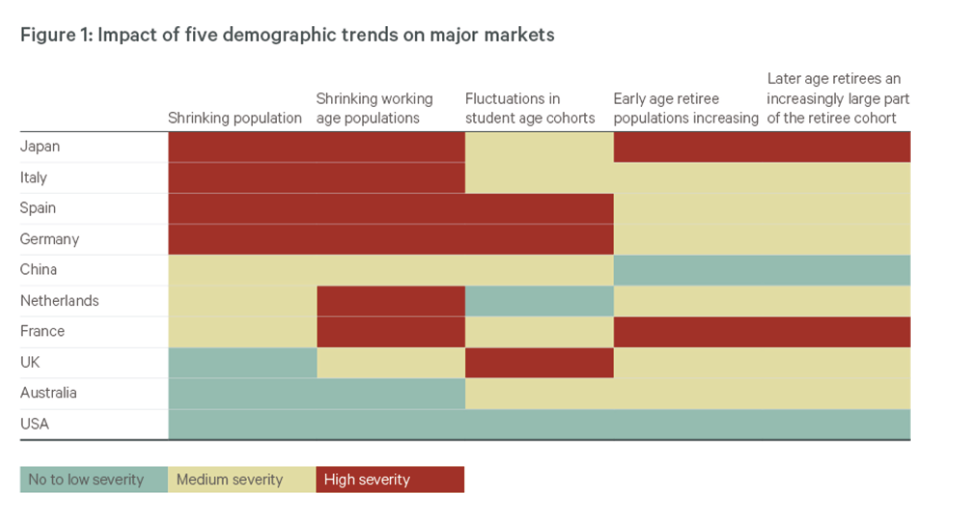

Across these markets, we observed five major trends:

shrinking populations;

shrinking working age cohorts;

fluctuations in student age cohorts;

increasing early age retiree cohorts; and

later age retirees becoming an increasingly large part of the retiree cohort.

We then graded the comparative strength of these five trends by severity to establish a demographics spectrum in order of most severe headwinds to most beneficial tailwinds. The results of our analysis, based on the United Nations 2019 Population Trends report, are represented in the table below.

We then categorised our major markets as broadly characterised by demographic headwinds, in a state of demographic transition, or demographic resilience.

In demographic headwind markets, investors should favour strategies that target established large urban population centres that may experience faster population growth than the country and where the current market size is sufficient to guarantee strong demand for logistics and residential property. These markets tend to be associated with lower trend economic growth and interest rates, making leveraged core cash flows attractive. In addition, these markets are associated with an increasing proportion of retirees and older retirees. Accordingly, we expect these markets to offer opportunities in senior living and higher acuity nursing homes.

In demographic transition markets, cyclical growth strategies are favoured. These markets tend to have high working-age population or urban population growth. Consequently, they are served by mixed-used schemes, certain office and retail segments. Strategies in these markets are potentially time-limited by increasing demographic headwinds as we move through the next decade or two.

Finally, in demographic resilience markets, investors might prefer to focus on strategies that benefit from strong population growth and higher associated trend economic growth. For example, these markets may support investment in the life sciences sector. In addition, these markets tend to have consistent student cohort growth, supporting student housing demand. Given that these markets tend to have higher trend interest rates, investments with inflation-linked cashflows will be more attractive.

In the remainder of this first article, and across the coming series, we explore how each of the five trends might impact our major markets – the US, UK, eurozone, Japan, Australia and China. We conclude this article with a review of Japan.

Japan: demography

The Japanese market foreshadows what is to come for many developed world nations. Its population peaked at 128.6 million in 2009 and has since fallen by 3 million. The childhood cohort was the first to fall, with the decline beginning in the early 1980s. This then flowed into sustained declines in the tertiary education cohorts in the mid-1990s and the working age population in the late 2000s. The pandemic years marked three key pivot points for Japan:

In 2020, Japan’s working-age cohort fell to less than half of the overall population, a first for a G7 nation. The trend will continue to fall to around 41% by the 2040s.

In 2021, Japan’s early retirees’ population started to fall outright. Consequently, it was the first year that only the over-80s cohort was still increasing in size. This trend is projected to increase into the mid-2030s.

In Greater Tokyo, the population stabilised at 37.4 million during the pandemic. It was driven by a sharp fall in foreign nationals relocating to the city and a smaller fall in internal migration, as fewer people moved for jobs. These pandemic-induced factors may end in 2022 and Tokyo may continue its previous growth rate, but some forecasters expect the population to continue to fall.

Japan: economy

The Japanese economy has struggled with decades-long low growth and deflation that occasionally flirts with sustained low inflation. Japan is a global leader in advanced robotics, but much of the manufacturing is outsourced to countries with lower labour costs.

Social care and retirement funding are managed at the national level with mandatory savings and centrally organised social care. Since 2000, the government’s Long-Term Care Insurance programme has provided retirees with social care on a means-tested basis, funded through contributions from the over-40s. Among the over-80s, care is typically provided in the community rather than in specialised residential homes, given the lack of healthcare workers. That said, there is a proportionately smaller but rapidly growing private sector senior living and nursing home sector.

Impact on real assets

Japan has remained a relatively attractive market for investment as urbanisation and relatively low interest rates offset a falling overall working-age population. As a result, real assets catering to Tokyo’s large domestic consumption market and the expanding urban professional – eg, logistics and residential – have remained attractive, especially given the low all-in cost of debt.

Greater Tokyo will remain one of the largest urban centres in the world, despite a slowly shrinking population. The opportunities of servicing the Japanese capital’s real assets needs will remain attractive. In addition, one might expect the market for privately owned retirement facilities to prove attractive, especially if advanced robotics and/or laxer immigration policies resolve the issue of labour.