Why it makes sense to have a targeted approach.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) is a high priority for real estate investors. Affording significant weight to ESG within investment decisions is prudent regardless of whether an investor has altruistic or financial motivations, given that ESG-based strategies deliver superior long-term capital protection, creation and growth.

Ensuring assets are energy efficient and adaptable without extensive refurbishment, for example, improves environmental outcomes as well as occupier appeal through lower energy costs/branding benefits and enhances landlord optionality. This will be reflected in higher rents and lower yields. Safeguarding social inclusivity increases commercial asset value and aids its social contribution. Communicating and collaborating with councils, landlords and local communities both promotes better governance and ensures assets are more ingrained in its micro-location and is accretive to long-term value.

ESG and financial performance are thus inseparable. Therefore, ESG considerations should permeate every facet of investment strategy from macro-sector allocations though asset selection and management to occupier profile. What this means in practice varies by investor, but there are three general tenets that can be applied.

The first tenet is that ESG strategies should be inclusive at all levels. The UN Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI) was created to guide institutional investors in developing a more sustainable global financial system. Interpreting this guidance, it is unequivocal that it is not the role of real estate investors to deprive any business or sector with access to the modern, well-specified floorspace they require to operate efficiently.

This means that all investable options should still be on the table for ESG-focused investors, including negatively perceived occupiers such as fossil fuel companies or power-hungry data centre operators. Indeed, excluding such occupiers may worsen ESG outcomes if they are forced to occupy poorer quality buildings, use inferior locations or their higher cost base limits as capital available to the investor isn’t a greener or more socially inclusive operational process.

That being said, investors can still influence behaviour. They can disproportionally favour occupiers with higher ESG credentials such as certified B Corporations (’B corps‘) which meet high standards of social and environmental performance, transparency and accountability. They can make space available to groups that are unable to pay market rents, but which still require space such as community or voluntary organisations, social enterprises or charities.

“ESG strategies should not just be about targeting the assets which already perform well”

The second tenet is that to make a meaningful impact, investors must enact positive change. That means focusing on valued-added strategies and not leaving it to the next owner to make improvements. ESG strategies should not just be about targeting the assets which already perform well. Quite the opposite in fact – true impact investing should seek out the weakest performers and improve them.

When ESG outcomes are maximised, the least operationally efficient and most wasteful assets are enhanced. Such assets have the greatest potential to reduce existing externalities and generate higher-value outcomes. Reconstituting a weak or failing asset into a high functioning, ESG-enabled asset delivers genuine positive change. Valued-added strategies which commit to actioning improvement works and revitalise the poorest assets will have the greatest impact

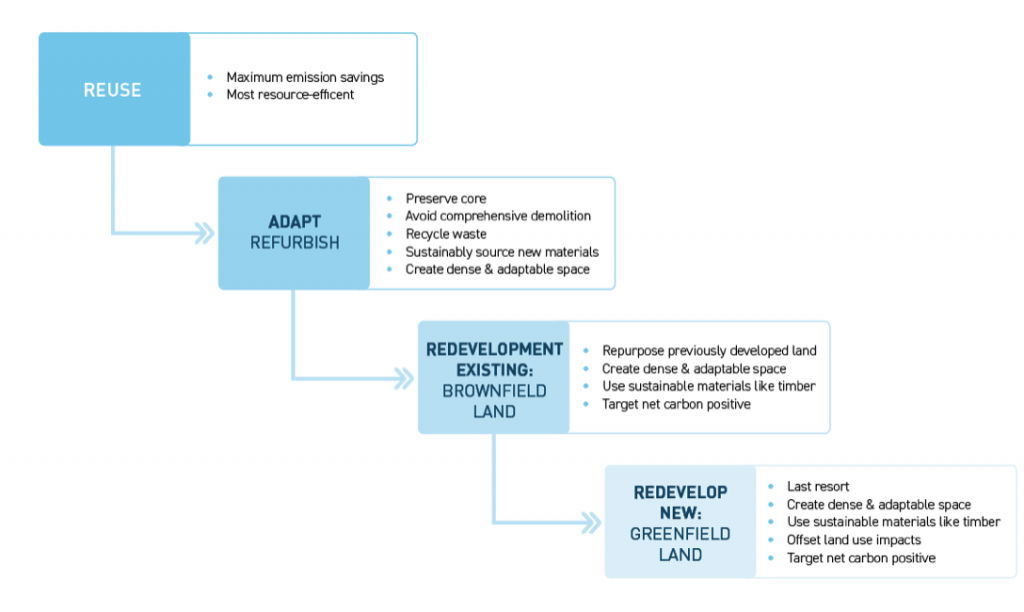

The third tenet is to apply a development hierarchy. Embodied carbon means that reusing existing buildings is always the most environmentally sound approach towards accommodating occupier demand. From a targeting perspective, this means that investors should acquire and create assets which are flexible and adaptable, allowing their use to evolve over time without heavy refurbishment or redevelopment.

While reuse is best, refurbishment and new construction with alternative/recycled materials will still be needed to fulfil changing occupier demand and facilitate growth. Indeed, it is estimated that two billion square metres of new building stock will be needed globally every year to 2025 to meet demand. That’s almost double the current amount of retail, office and industrial space in Europe, according to data provider Real Capital Analytics (RCA).

ESG-focused investors should not preclude new development. Far from it. To make a meaningful impact, they should support new development where it is needed using net zero or carbon negative construction processes on brownfield land. Doing so will lower aggregate construction-related emissions and land-use requirements.

Strategies which utilise modern construction techniques, combined with sustainable, locally sourced materials like timber can remove more carbon from the atmosphere than they create, ie, they are net carbon positive. Construction costs are lower and rental premiums equivalent of up to 9% are achievable for timber buildings, according to our research. Timber is not the only solution. Innovative research is underway into other materials, like ‘green’ and graphene-enhanced concrete. However, timber represents the most readily available, proven, sustainable material which can be used today. It represents the best current option.

Figure 1: Elevating ESG: adaptive reuse hierarchy

To conserve land, priority should be given to brown over greenfield sites. As the green agenda takes hold, it will become harder to secure planning consent for greenfield sites. Adopting a brownfield-first strategy therefore also mitigates future planning and development risk alongside promoting the efficient use of land. Where greenfield development is unavoidable, offsets can be sought elsewhere within the portfolio to mitigate environmental impacts by, for example, greening roofs, planting trees or enlarging public spaces to support biodiversity. Density should be encouraged to maximise the amount of accommodatable occupier demand. To broaden social opportunity, local businesses should be incorporated into the development tendering process.

In summary then, investors should target assets with an ESG-angle for sound financial performance and positive environmental, social and governance outcomes. A practice strategy to do this can be built on three tenets: inclusivity, value-added favouritism and the adoption of a development hierarchy. Investors pursuing this approach should harness the greatest meaningful positive ESG impacts and the most attractive risk-adjusted returns.

![<div class="entry-title-container"><div class="entry-title" style="width: 85%; display: inline-block;">James Boyle article[56]</div><div class="badge-container" style="width: 15%; display: inline-block; text-align: right;"></div></div>](https://www.propertychronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/James-Boyle-article56.jpg)