Following yesterday’s announcement from the Chancellor, the Property Chronicle editorial team asked our contributors for their initial reactions.

Adrian Elwood

Adrian Elwood has been researching and investing in the listed real estate sector for over thirty years. He was a member of the listed real estate team at Henderson Global Investors from 2004 to 2010. In September 2012 he established The Clerkenwell Matterhorn Fund, a Malta domiciled PIF with an absolute return mandate to invest in the sector.

The Chancellor painted a picture of a slow growing economy which continues to increase employment at a steady rate and in which inflation has peaked. Leaving aside whatever else is going on in the world this is an economy which needs low interest rates and which is likely to get the low interest rates which it needs. This is not the climate for a boom in real estate, but it is broadly supportive. Other than that, there was nothing in the speech for the commercial property market with the possible exception of Aberdeen where the ability to transfer tax credits on the sale of oil fields may stimulate a further round of activity in the North Sea. But then, nor should there be. All that the commercial market needs is broadly supportive economic conditions, a stable tax environment, access to credit and reassurance that, despite all of the Brexit related evidence to the contrary, there is a steady hand holding the tiller. The Chancellor saved the bad news for the supporting documentation: CGT is to be levied on foreign owned property from 2019. Given the importance of international buyers it is easy to jump to the conclusion that this will trigger a (downward) repricing of the market. More likely, it will lead to more widespread use of the REIT regime and the onshoring of numerous offshore vehicles.

Much of the pre-budget coat trailing focussed on our ‘broken’ housing market and here the Chancellor didn’t disappoint, rattling through an extensive range of funding packages, loans and guarantees adding up to no less than £44bn over the next five years.

As he said himself, there is no magic bullet but, by introducing a range of measures, both fiscal and structural, he is increasing the chances of meeting his target of 300,000 new homes a year by the mid 2020s. Having said that, the private housebuilders are already running at close to post-war peak output. The population is bigger than it was in the 1960s and low interest rates mean that mortgages are surprisingly affordable so there is no reason why output shouldn’t reach new levels, but the real issue is the persistent under provision of subsidised housing. Moving housing association borrowing from the public to the private sector will undoubtedly help as will the changes to the Universal Credit regime but otherwise the Chancellor had relatively little to say about this vital sector of the market.

The sting in the tail was the announcement of an urgent inquiry into the gap between the rate at which planning permissions are granted and the commencement of development to be led by Oliver Letwin, a man not known for taking no for an answer. He is due to report in the spring, with action promised if there is evidence that planning permissions are being hoarded for economic rather than technical reasons. When house prices are rising rapidly there is clearly a theoretical incentive to capture the geared profit on consented land by holding onto it. However, the reality of the post-crash world is that finance is expensive, if it is available at all, planning permissions only last for three years and the major developers are able to buy enough land to support their activities without undermining their margins by inflating the price of consented land. Consequently, the land profit is more likely to erode over time than it is to grow and the incentive is therefore to crystallise the land profit as quickly as possible. The only way to do that is to move on to the next stage, the crystallisation of the development margin, and that can only be achieved by selling to a developer or developing out the scheme. Mr Letwin is likely to find that there is a wide variety of explanations for the 275,000 stock of unexecuted planning permissions in London, but frustration rather than greed is more likely to be the common factor. Is a Tory government really going to legislate to force developers to build out loss making or unviable schemes?

In order to get more houses built the government can either build them itself or create a climate in which developers are encouraged to build and people are encouraged to buy (or rent). Given the state of the public finances and the fact that £1bn only buys you about 5,000 homes, building them isn’t a realistic option so the government can only extend the support which it is already giving to the private sector. The housebuilders have been operating in an unusually benign environment for a number of years and these new measures mean that, all other things being equal, they will continue to do so for some time to come.

Peter Warburton

Dr Peter Warburton is director of Economic Perspectives Ltd, an international consultancy, and managing director of Halkin Services Ltd. He was economist to Ruffer LLP, an investment management company, for 15 years and spent a similar length of time in the City as economic advisor and UK economist for the investment bank Robert Fleming and at Lehman Brothers. Previously, he was an economic researcher, forecaster and lecturer at the London Business School and what is now the Cass Business School. He published Debt and Delusion in 1999. He has been a member of the IEA’s Shadow Monetary Policy Committee since its inception in 1997. He is a contributor to the Practical History of Financial Markets course run by Didasko, an education company, at Edinburgh University, and teaches occasionally at Cardiff Business School.

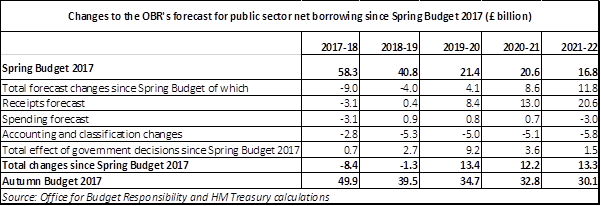

Barely a month ago, the Financial Times concluded that the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Hammond, would have no room for manoeuvre in this Budget, due to downward productivity revisions by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). Not a bit of it: the Chancellor found £6bn of stimulus for fiscal 2018 and almost £10bn for fiscal 2019. In all, an extra £6.3bn was found for the NHS: £3.5bn for upgrading buildings and improving care and £2.8bn for improving accident and emergency performance, reducing patient waiting times and to meet increased demand. Has ‘Spreadsheet Phil’ had a heart transplant, or at least a change of heart? The political realities were always tugging this Budget towards a fiscal relaxation and this has duly occurred. The question was whether a dry Chancellor could deliver a wet Budget, and the answer is an emphatic ‘yes’. Those wonderfully flexible fiscal rules have been flexed even further (see table). The extra spending allocation of £3bn to help prepare for EU exit looks rather arbitrary, but will doubtless come in handy for some other purpose. There is plenty of mañana in this Budget: the fabled 300,000 net additional homes each year is an aspirational target for the mid-2020s. There is also a larger dollop of reality than is commonly found in the official economic projections. The assumed growth of national output falls to the range of 1.3 per cent to 1.5 per cent in each of 2018-2021. Given the pace of population growth, this translates to GDP per capita growth of only 0.7% to 1% in the forecast period. Expectations for this Budget were ankle-high, but Mr Hammond has achieved a knee-high Budget. Whether it is enough to save his political skin remains to be seen: these measures require formalisation in the passing of the Finance Bill, which will be no easy task given the government’s lack of parliamentary seats. However, there may be sufficient ammunition here to spike the Labour Party challenge and bring some much-needed relief to the embattled prime minister. One uncomfortable footnote: assumed domestic spending in lieu of EU transfers from 2019-20 will exceed the value of transfers currently made to EU institutions.

Will Stebbing

Will Stebbing is Head of New Homes & Investments at Douglas & Gordon, a market leading estate agency in central and southwest London. His role involves advising on the disposal and acquisition of land, development consultancy and the sale of new build properties through Douglas & Gordon’s network of offices. Will studied law at Oxford University before working at Strutt & Parker and Savills. He has a significant breadth of knowledge across the residential property market including prime central London, country houses and residential developments.

A policy for the benefit of a few; a different few but still only a few.

I’ll admit it, I was wrong. In the run-up to the budget there was hope that there would be an easing of the stamp duty burden. Weary and cynical I was convinced this was just wishful thinking from agents desperate for some sort of break from the government.

And then the Chancellor pulled a rabbit out of the hat. Soon-to-be first-time buyers (bad luck if you completed yesterday) will now make significant savings as they begin their climb up the property ladder. The office is filled with optimism, younger members of staff are online and hoping their renting days are over.

But alas, from my London-centric seat in the audience, the magician’s rabbit is far too fluffy.

The policy has already made a good headline and is therefore a shrewd move from a government in turmoil. A gift exclusively for the millennials will be welcomed among this particularly disgruntled group of voters.

It will also be a relatively cheap policy to implement. When the slab system of SDLT was scrapped even less of the revenue came from the sub £500,000 property transactions, so this will not cost the government much.

I am sure there will be an increase in applicants in the lower echelons of the market but this was not the broken part of the housing market. This is like putting on an ankle support when you actually need a back brace. The fundamental issues remain.

A fluid property market, that is advantageous for the wider economy, requires transactions at all levels. Without wanting to oversimplify a very complex market, there are three types of buyers, each of which need the desire and the ability to move.

First time buyers

The desire has always been there. Generation Rent may be ‘a thing’ but deep down nobody wants to be a part of it, everybody has a desire to buy. In terms of ability, FTBs have been offered numerous handouts to help them onto the ladder: Help To Buy, Property ISAs and low interest rates. The problem has been capital values and the abolition of SDLT for FTBs may be the cherry on the cake but an increase in demand will only push capital values up.

Upsizers

These are the buyers selling their 1/2 bedroom flat and moving to a large 2/3 bedroom flat or small house. The issue here is that this step on the ladder doesn’t exist anymore. If you bought your first property in the last seven to eight years you’ve done very well and have a healthy amount of equity. With a healthy deposit, low interest rates and high SDLT (at this level) you are going to skip this step and jump straight to the family home. Sure, you may not have the kids to fill it yet but why would you buy a 2/3 bedroom flat that you will grow out of in a few years? With the market as it is you aren’t going to make back your stamp duty when you sell.

This rotten rung of the property ladder is a whole article in its own right. This should be the engine room of the market with a high turnover of stock. Developments across London are full of these flats but the demand is just not there. The buy-to-let sector has been decimated by the 3% SDLT surcharge and the gradual removal of tax relief against mortgage repayments. The end users are skipping the step due to high moving costs (including SDLT) and their desire for a more permanent home. And so the windows in the towers of Nine Elms remain dark.

Family home buyers

Previously this was the third rung of the ladder but for the reasons above it is now the second. This part of the market is steady. People want to move into a family home and settle for 10 plus years. The costs are high and everyone wants to ‘buy well’ but this property is much more than just a financial asset. A SDLT reduction here would have been nice but it was always implausible. It wouldn’t have won many new voters and would have cost an awful lot in SDLT receipts.

Enough of the pessimism though. Millennials deserved a break; the baby boomers and Generation X have had plenty of their own. However if it pushes prices up, that extra toast at Christmas may be from a poisoned chalice.

Clive Emson

Clive Emson is the Chairman of the eponymous auction company that he formed in 1989 to provide an independent land property auction facility for statutory authorities, private clients and estate agents with clients that wish to consider auction as an alternative marketing method. Over 850 high street agents from Essex to Cornwall now help to introduce lots and distribute the 20,000 catalogues published for each of the eight auctions held each year. Prior to 1989 Clive was the national property auctioneer for Prudential Property Services and regional professional director for the South East. He is a Chartered Surveyor, honoured member of the National Association of Estate Agents and a member of the National Association of Valuers and Auctioneers. Clive Emson Auctioneers are now the 5th largest property auctioneer in the UK in respect of volume and value of lots sold in the UK.

The budget provisions were certainly a step in the right direction but from my experience as a property auctioneer, the tinkering with stamp duty is more of a sound bite than making a real and tangible difference in the first time buyer’s ability to get on the housing ladder.

When the 3% hike in stamp duty for second homes was announced at the beginning of the year the prices at auction were 10% higher than anticipated and fuelled by investors wishing to “save” the 3%! The prices have remained at or above that level since the new rate was implemented.

It is inevitable that making home buying more attractive to first time buyers will increase demand which, in turn will put added pressure on prices – the laws of supply and demand have not changed since time immemorial.

The only way to solve the housing shortage is to build more homes and ensure that the existing stock is actually occupied – the 100% rate levy will encourage occupation but penalise those wishing to refurbish and upgrade properties before selling/letting.

In summary, the announcements yesterday highlight the problem but until planning procedures are streamlined and mortgages are made less difficult to obtain, the measures are no more than a sticking plaster where a tourniquet is required.

Julian Jessop

Julian Jessop is Chief Economist and Head of the Brexit Unit at the Institute of Economic Affairs.

Over 24 hours and counting, and the autumn Budget still hasn’t unravelled. These days that probably counts as a win. The newspaper coverage has predictably split along party lines, but the consensus seems to be that Philip Hammond played a bad hand reasonably well. The Chancellor avoided some obvious pitfalls – such as lowering the VAT thresholds for small businesses – while spending smallish sums of money in enough areas to keep the kiddies happy at Christmas.

Nonetheless, any cheer has been overshadowed by two pieces of bad news. The first is the much gloomier assumptions about productivity, an unwelcome gift from the elves at the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). The OBR, like most forecasters, has consistently been too optimistic about productivity since the financial crisis. It has now chucked in the towel and assumed that output per hour worked will remain significantly below its pre-crisis trend. This in turn implies a lower profile for economic growth and a worse outlook for the public finances.

But on top of this, the Chancellor has added to the budget deficit further with a package of tax cuts and increases in public spending. Indeed, he appears to have redefined the concept of a ‘balanced budget’. It is no longer about eliminating the deficit. It now seems to mean responding to as many competing political pressures as possible. As a result, the deficit, initially supposed to have gone by 2015, is still expected to be £25bn in 2023.

That may not be a big number in itself. But since 2000, when the government last balanced its books, public sector debt has climbed from 28% of national income to more than 86%. Even at current low interest rates, that is a huge burden to hand to younger generations. The Budget sweetener of a few more years of cheap rail travel is not much consolation.

As it happens, I think that the OBR’s assumptions about productivity are now too pessimistic. This might yet rescue the fiscal numbers too. The OBR’s forecasts are taken too seriously. In this Budget, for example, a lot was made of the fact that economic growth is forecast to slow from 1.5% in 2017 to 1.4% in 2018 and 1.3% in 2019, before picking up again. As if anyone can forecast GDP to the nearest decimal place!

To be fair, the OBR acknowledged that ‘huge uncertainty remains around the diagnosis for recent weakness and the prognosis for the future’. But it is therefore all the more important to question these forecasts, and the assumption that the UK’s relatively poor performance on real wages and on productivity is due to a low level of investment. Too often this seems to lead to the conclusion that the only way to boost living standards is to increase investment by, or directed by, the state.

For a start, the weakness of real wages can also be explained by a series of exceptional factors since 2010, including two hikes in VAT, shifts in the composition of the labour market, the public-sector wage freeze, large scale migration from the EU and, most recently, the fall in the pound. Crucially, all these pressures have now ended, or will do so soon, while the labour market has continued to tighten. As a result, real wages should recover of their own accord.

In the meantime, the UK’s productivity performance has not been as bad as the headlines suggest. In part it is simply the flipside of rapid growth in employment – a good thing – due to the UK’s relatively flexible labour market. As the economy runs short of new workers, companies will have every incentive to prioritise gains in productivity once more.

Two other developments should also help to raise productivity with no further action from the Chancellor. One is the return of interest rates towards more normal levels, increasing the incentive for banks to lend and encouraging the reallocation of resources to more productive uses. The other is an easing of uncertainty about the impact of Brexit, which should encourage companies to look again at new investment projects.

The upshot is that now may actually be precisely the wrong time to slash forecasts – or indulge in a splurge in public investment. Indeed, there is more that the Chancellor could do to help without spending large amounts of other people’s money. A fundamental overhaul of our highly restrictive planning laws would have been a good start. Liberalising the planning system and freeing up small parts of the green belt would transform the housing market.

Instead, the Chancellor focused on beefing up existing subsidies and guarantees. He could have used the money to abolish stamp duty – a particularly inefficient tax that clogs up the residential market. But by only doing so for first-time buyers, the main winners will be homeowners and developers who can now charge the lucky few a higher price. This will be at the expense of others who are not obviously any less deserving of a visit from Santa – such as growing families looking for their next home.

Overall, then, this was a ‘safety first’ Budget that left the public finances in a perilous state. The Chancellor must hope that the doomsayers will be proved wrong. But here at least the recent news has been encouraging. The UK economy has performed better than most forecasters – including the OBR – had expected after the vote to leave the EU. All our Christmases could come early if the government gets Brexit right.