The vast majority of the British public thinks that affordability is one of the big issues in the housing market, with half rating it is the single most important issue. Those are the results of an exclusive poll for The Property Chronicle by Electoral Calculus and pollster Find Out Now.

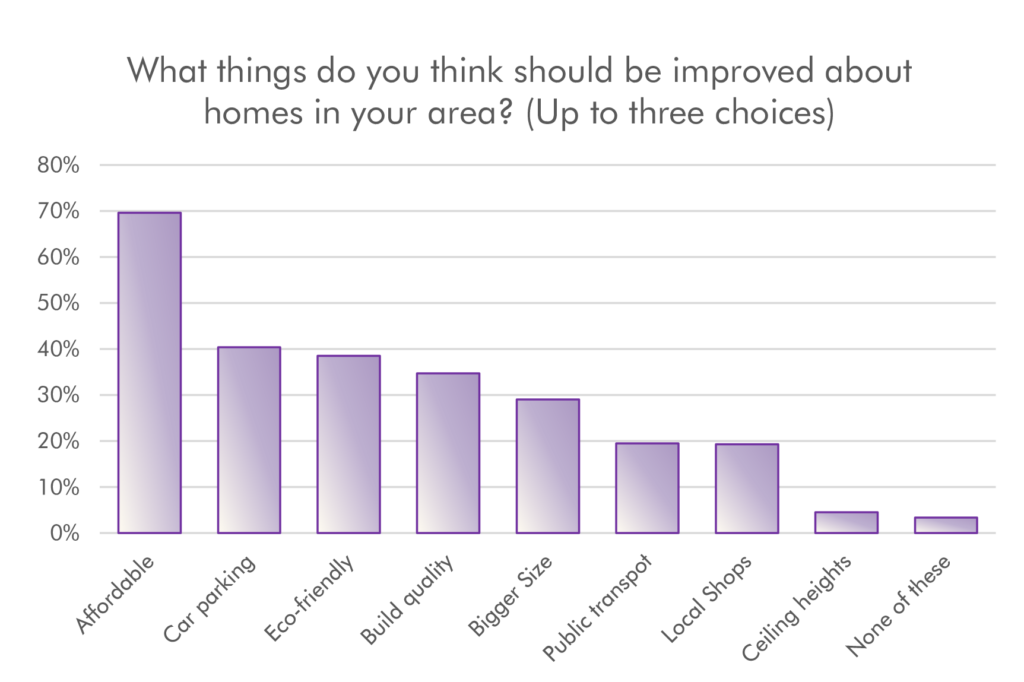

We interviewed a representative sample of the public, asking them what they thought should be improved about homes in their area. Participants were asked to select up to three items from this list: better car parking, better construction quality, better public transport links, bigger average size, higher ceiling heights, more affordable, more environmentally friendly, more local shops or none of these.

The results are shown in the first graph, which excludes the 9% of the public who didn’t know.

We see that affordability comes top of the list, with a whopping 70% of the public naming it as one of the top three housing issues. Coming behind affordability were desires for better car parking (40%), more environmentally friendly properties (39%) and better construction quality (35%).

There was more modest support for bigger property sizes (29%), better public transport links and more local shops (both on 19%). Ceiling heights are not seen as a major issue. Importantly, only 3% of the sample thought that none of the given options was needed.

A cynic might say that this only shows that people want cheaper, greener, bigger and better homes with somewhere to park. Who wouldn’t? But it’s the relative importance of the issues which is striking. The public put the housing affordability crisis far ahead of other issues, such as tackling man-made climate change.

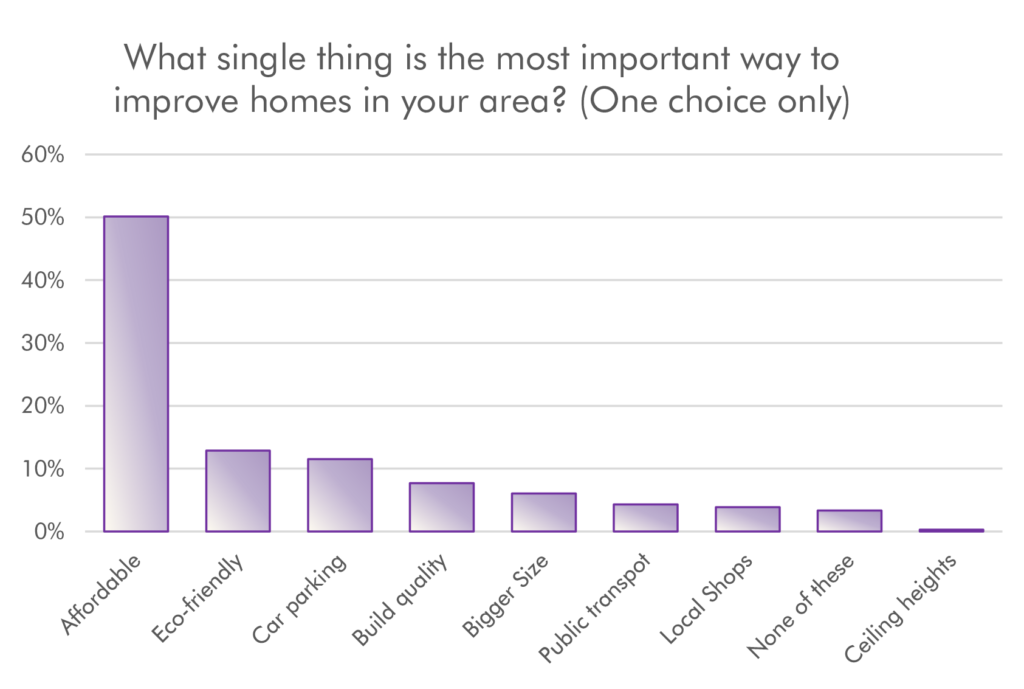

We also asked our interviewees what single thing is the most important way to improve homes in their area. The results of this question were even more stark and are shown in the second graph.

Half of our sample, excluding the 9% of don’t knows, named affordability as the single biggest issue with British housing, far ahead of all other issues. Environmental concerns came a long way behind on 13%, with fewer than one respondent in every seven naming this issue. Better car parking (on 12%) was the only other item which scored more than 10% support.

There was some variation between various age groups. Of those aged between 18 and 24, nearly two-thirds (64%) cited affordability, with environmental concerns and build quality equally chosen at around 10%. For those aged over 65, affordability was mentioned by 34%, with parking and the environment scoring about 15% each. There were some expected regional variations too, with 52% of Londoners concerned about high prices but only 32% of those in the North East.

These results show serious public concern about housing affordability, which dwarfs other issues in perceived public importance.

The political implications ought to be clear. Politicians of all parties would be wise to consider the public’s priorities when it comes to housing. For example, there has been much discussion recently about changes to residential housing in order to combat man-made climate change. These include roof, wall and floor insulation, and the replacement of gas boilers with heat pumps, hydrogen boilers or heat networks. The UK Committee for Climate Change has been saying for some time that British homes are “unfit” for the challenges of climate change.

But how much are the public going to listen to these arguments, when so many more people are concerned about housing affordability compared with environmental issues? The climate agenda will also likely increase short-term costs for property owners, which makes the affordability problem even worse.

Some good advice for politicians might be to talk about affordability first to convince the public that you understand their concerns. Once that’s done, you might have the public’s trust and permission to raise the environmental issues.

“Where supply is rationed, but demand is not, then basic economics will predict higher prices”

But should the government try to lower house prices? Although 70% of our poll supports it, why should the government interfere in the free market for housing? One answer is that there hasn’t been a free market since the 1940s, when planning permission was introduced for most new development. Central and local government have since exercised tight control over the supply of new housing. Where supply is rationed, but demand is not, then basic economics will predict higher prices.

If we accept that high house prices are due to regulatory failure rather than market failure, what can the regulators do to tackle it? The obvious approach is to reduce controls on new development and make it easier to build new homes. The current government has already made some moves in this direction with a target of 300,000 new homes a year by the mid-2020s. But the public are already divided on whether they would like new development locally. In our poll in the last edition of The Property Chronicle, people were fairly evenly split between support, opposition or neutrality to new local development.

The political challenge is tough: cheaper homes follows from more new homes, but many people don’t want new development. Something has to give.

Technical note: Find Out Now interviewed on 17 August 2021 a sample of 2,011 GB adults which was weighted to be nationally representative by gender, age, social grade and area. Find Out Now is a member of the British Polling Council and abides by its rules.