Quantitative Easing (QE) has come under fire from many sides; it is charged with lowering capital expenditure and productivity, inflating pension costs, discouraging saving and widening inequality. The central banking alumni of Goldman Sachs, alias the vampire squid, have had enough, embarking on a crusade to “set the record straight” on QE.

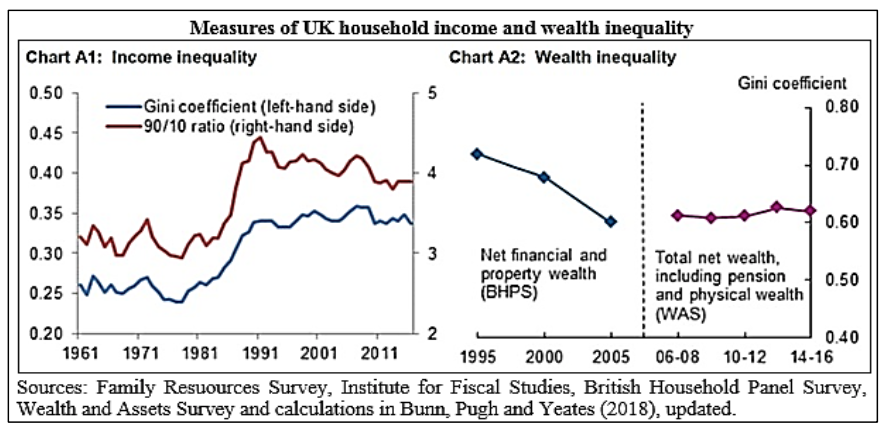

Under Mario Draghi’s tutelage, six authors have collaborated in a heavyweight ECB working paper entitled Monetary policy and household inequality and, Bank of England deputy governor Ben Broadbent delivered his take on “The history and future of QE” a few weeks ago. Cutting to the chase, both papers conclude that “monetary policy in recent years benefited most households and did not contribute to an increase in wealth, income or consumption inequality.”

The core argument is that QE has boosted aggregate demand and reduced unemployment, helping the poorest households who have little or no financial wealth. The authors also claim, in Europe at least, that real house prices have not risen materially, and real equity prices have not recovered to their 2007 peaks.

However, there are several objections to this defence of QE. When we look longitudinally at the experience of different types of households, we find that older households with even modest financial wealth have prospered much more than younger households. Their wealth has been invested internationally and has generated much better returns than those obtained from European financial markets. Those with the largest mortgages gained the most from the compression of interest rates and debt service costs. While labour markets have tightened, real wage growth has been extraordinarily weak. It has been necessary for wage-earners in the lower reaches of the distribution to work longer hours or take second jobs to supplement their incomes.

The ECB and Bank of England are also coy about the extent to which credit relaxation in Japan and China, from 2015, has contributed to rising living standards. In the Euro area, particularly, net exports to Asia have been an important contributor to economic growth. The distributional consequences of QE have politicised monetary policy and this genie will not readily be re-bottled.

(This article originally appeared in the Halkin Letter)