In 1604, the English judge Sir Edward Coke declared that “the house of everyone is to him as his Castle and Fortress.” The intervening years turned the saying to “and Englishman’s home is his castle.” With apologies to the Scots, Irish and Welsh, it is perhaps not surprising that the widespread aspiration for home ownership is ingrained in our national psyche.

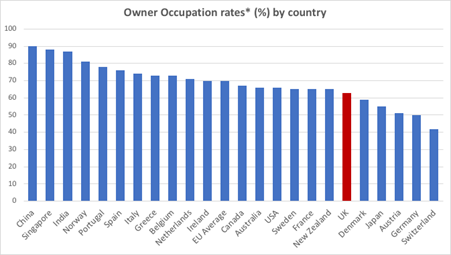

But Britain is not quite the nation of homeowners we believe ourselves to be. Rather than having the highest levels of owner occupation among developed nations, the UK is nearer the bottom of the league than the top. Growing levels of renting since the early noughties have depressed the proportion of mortgaged homeowners so that rates of owner occupation are now lower than they were 25 years ago and lower in comparison with Europe, North America and Australasian countries as well as the economic giants of India and China.

Understanding the reason for this decline is important to fully understand the resulting economic and social impacts and to enable appropriate responses and policy to be made. The issue of housing imbalances in the United Kingdom is persistent and concerning. The problem has been exacerbated by decades of market dynamics and policy decisions. Land ownership, which is seen to have traditionally favoured landlords over tenants, is under threat. In recent years, in the face of disparities in wealth distribution. There has been a growing call for a transfer of housing wealth back from landlords to tenants. But this has its own risks which are beginning to be seen where draconian anti-landlord regulation discourages investment, reduces supply and has an inflationary effect on rents.

A more sophisticated approach is needed, suited to the 21st century, which breaks the age-old adversarial landlord-tenant relationship and more closely aligns the interests of both parties. If this is not achieved, the housing market risks becoming a permanent instrument and mechanism for perpetuating social divisions. The iniquities created by current mechanisms need to be addressed both imaginatively and accurately.

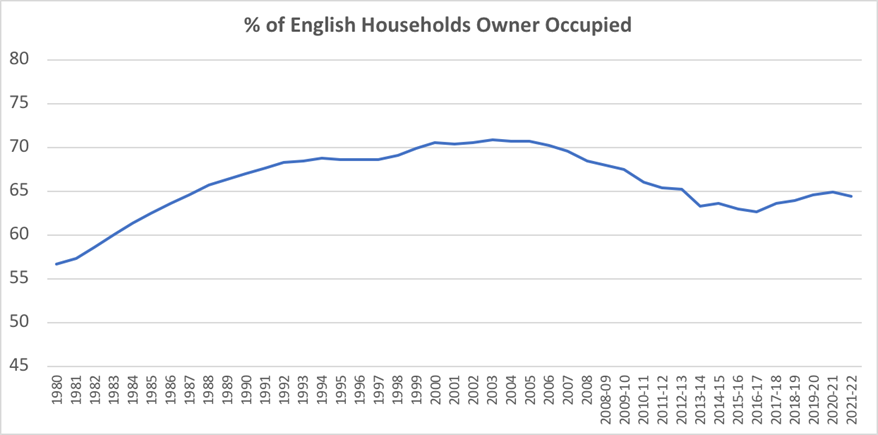

The UK Labour Party, has stated in draft policy that its aim is to increase home ownership in the UK to 70%. On the face of it, this should not be a difficult task to achieve; the UK reached this level of owner-occupation back in the early noughties. Owner-occupation rates were over 70% between 1999 and 2007. They fell after the global finance crisis in 2008 and have only recovered marginally since their nadir of 63% in 2017.

In practice, the challenge of increasing owner occupation again could prove considerable for any political party. This is because structural change in housing markets has created barriers to home ownership which did not exist in 1999. Mortgage affordability, in terms of meeting monthly repayments from household income, is much less of a problem than raising a deposit. It is the amount of equity needed to become an owner which is creating barriers to both entering the market and “trading up.” It is balance-sheet inequalities rather than current account inequalities which are creating very different experiences of affordability for different groups. Crudely, the housing market is separating the equity-haves from the equity have-nots.

*=most recent period for which data is available.

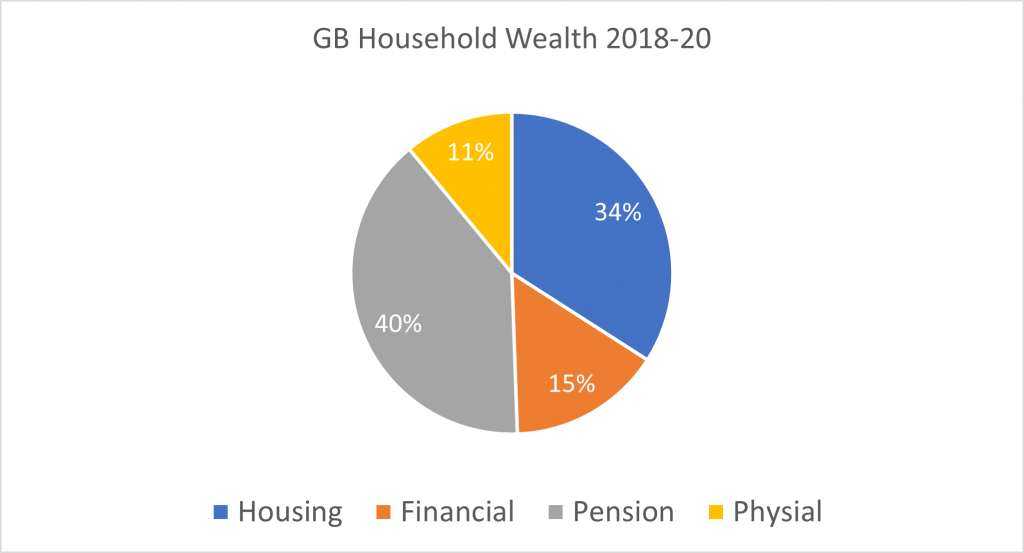

A recent Joseph Rowntree report showed that household wealth was significantly affected by housing value and differed between regions and different groups according to housing market conditions and rates of home ownership. Overall, housing accounts for over a third of all household wealth.

In the aftermath of WWII, the UK witnessed a period of significant growth in housing wealth. This growth was largely driven by the increasing ownership of homes by ordinary people. Mutual societies and mortgage lenders facilitated the mass transfer of land and equity from a few landlords to more than two-thirds of UK households by 2003. However, now this trend has started to reverse, a concerning difference in wealth levels and prospects for wealth accumulation occurs between different households.

Housing inequality has far-reaching consequences, impacting access to stable housing, financial security, and overall wellbeing. If left unaddressed, it can lead to a growing gap between those with access to housing equity and those without. While the Labour Party may recognise the importance of tackling this issue, traditional approaches, such as mortgage lending, may not be sufficient to bridge the divide.

One potential is to address housing inequality by utilising digital technology for the tokenisation of housing equity. Blockchain has already demonstrated its transformative potential in various sectors, including finance and art, with the rise of NFTs and cryptocurrencies. These technologies offer a secure and transparent way to represent assets digitally, making them ideal for the real estate sector.

This approach could revolutionise the way housing equity is transferred and owned, with significant benefits over metaverse and crypto tokens in that tokenised property would represent a security backed by tangible real-world assets, ensuring its stability and reliability. Tokenisation of property would involve converting real estate assets into digital tokens that can be securely traded on a blockchain-based platform. This opens up a range of possibilities for wealth distribution in the housing market. Under such a system, landlords could be incentivised to co-own more diversified portfolios and share a portion of their equity with tenants.

One innovative solution to transfer housing wealth from landlords to tenants is to incentivise landlords with suitable tax breaks to depreciate their holdings over a specified period. For example, a landlord could be encouraged to give, say, 2% of a property’s value each year to tenants who pay full market rent. The implementation of technology to tokenise the property could eliminate the need for complex legal arrangements associated with conventional shared ownership.

Tradeable tokens granting landlords the first right of buy-back could be created, enabling all tenants, regardless of their credit status, to build equity in the housing market without requiring a large initial deposit or any problematic legal agreements. The acquisition of tradeable, tokenised equity would be in parallel to a continued renting arrangement. Rights, responsibilities and rent, would remain otherwise unchanged between landlord and tenant.

This approach ensures that wealth is progressively shared by tenants and could encourage more widespread access to property ownership, without reliance on debt.

Tokenisation of housing equity offers other benefits too:

- Landlords could co-own diversified property portfolios, reducing the risk associated with single-property ownership.

- Tokenised assets could be associated with professionalised management, enhancing standards in the private rented sector.

- Any capital appreciation in the asset should be reflected in the trading value of tokens, which is then shared by tenants, contributing to their financial security.

As we move into an uncertain and disrupted future, it is essential for governments, legislators, and policymakers to consider and embrace innovative technological approaches like this to create a more equitable housing landscape for all citizens. Failure to do so may result in a growing divide between property owners and housing users, a situation that is undesirable for any government, regardless of its political ideology. It is time for something different: bold and forward-thinking measures to tackle housing issues head-on.