How China’s reopening may light fires across the global economy.

At the beginning of 2023, if we have certainty about anything, it’s how uncertain the path is for the global economy – unlike in 2021 or 2022, when the destination (higher inflation and higher rates) seemed clear to us.

Perhaps most underappreciated are the two-sided risks from China’s chaotic reopening. Views appear to have converged around how it will play out: near-term disruption followed by a potent post-Covid mini-boom in the second quarter of the year. Good news for China and good news for asset markets.

“Neither economists nor epidemiologists have had a particularly impressive forecasting record over the past two years”

Maybe so. But much remains unclear about China’s Covid situation, let alone what will happen as normal economic life resumes. Neither economists nor epidemiologists have had a particularly impressive forecasting record over the past two years.

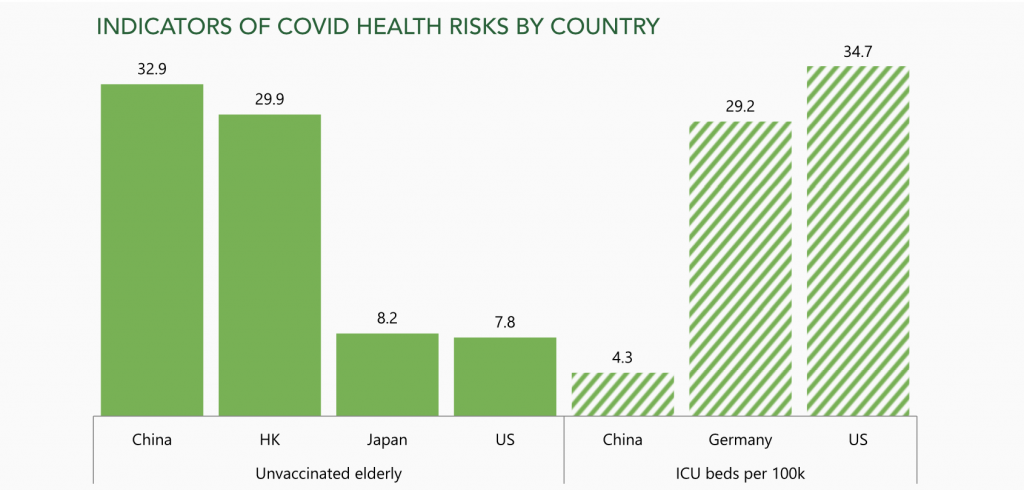

There is lots of emphasis on reopening, probably not enough on chaos. This month’s chart reveals the proportion of China’s unvaccinated elderly population and the shortfall in China’s healthcare system to look after those who become seriously ill.

It is also difficult to estimate the efficacy of China’s vaccines in protecting against severe illness. And it’s anyone’s guess exactly how many people are currently infected with the Omicron variant – although it’s likely to be in the hundreds of millions.

Plenty of countries have permitted uncontrolled spread of the Omicron variant. None have dismantled their Covid controls so abruptly, with such limited population immunity against the virus.

For most of the past three years, China’s goods economy has been shielded from Covid by continued lockdowns and restrictions. The service economy was sacrificed to keep factories open. But in the coming weeks, lots of people won’t make their factory shifts. At the peak of the Omicron wave in the US, 5% of the adult population was off work for Covid-related reasons, despite continual virus circulation in the previous two years and access to the most effective mRNA vaccines (US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey). Labour shortages will surely be even more acute in Chinese factories. Soaring demand for labour-intensive consumer services must contend with a Covid-disrupted workforce. China’s reopening will fan the inflationary flames, just as we saw in the West.

China’s ‘exit wave’ is unlikely to be smooth sailing and Xi Jinping’s efforts to prioritise the economy could easily backfire – that’s the ‘bad news is actually bad news’ scenario.

Optimists might argue that, after a short period of manageable chaos, China will enjoy an unexpectedly powerful rebound, one that defines the 2023 macroeconomic landscape. The three bears disappear off into the woods and Goldilocks returns: US disinflation, peak Federal Reserve (Fed) hawkishness and a China-led growth acceleration. It’s certainly possible.

But would this really be good news for markets?

Homegrown inflation in China, higher commodity prices and relief from a strong dollar might trigger a risk-on environment. However, that would be unlikely to last long, given the inevitable hawkish response from twitchy central banks. Until inflation pressures subside dramatically, good news on the economy will probably be bad news for risk assets.

Perhaps it is much simpler than everyone thinks. Collateral damage from China’s reopening merely accelerates a global earnings slump. An unexpectedly strong rebound, especially if accompanied by a resurgent property market, will force the Fed to hit the brakes even harder.

Either way, risk assets cannot escape their fate. If Fed Chair Jerome Powell is serious about emulating Paul Volcker’s feat of truly taming inflation, financial conditions may need to tighten significantly further in 2023. If so, investors could suffer additional burns to their portfolios.

Originally published by ruffer.co.uk and reprinted here with permission.