The physical market cycle analysis of five property types in 54 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs).

So unique – GDP growth dropped 1.4% in 1Q22, yet the Federal Reserve still increased the Fed Funds rate by 0.5% instead of 0.25%, a jump they have not done in 20 years. Supply chain pressure continued pushing prices up and the labour market got even tighter, but wage growth did not keep up with the CPI. The stock market is repricing risk with a 20% decline YTD and short-term interest rates have jumped with 10-year treasury at 3+%. Add the oil shock and food price increases to keep the economy slower. But – it is employment that drives demand for real estate and that demand (with 438,000 more jobs in April) is strong, pushing occupancies up in almost all cases.

Office occupancy decreased 0.1% in 1Q22 and rents increased 0.2% for the quarter, but were down -0.7% annually. Industrial occupancy improved 0.2% in 1Q22, and rents grew 1.7% for the quarter and were up 7.4% annually. Apartment occupancy decreased 0.1% in 1Q22, and rents grew 2.5% for the quarter and were up 4.2% annually. Retail occupancy improved 0.2% In 1Q22, and rents grew 0.6% for the quarter and were up 1.9% annually.

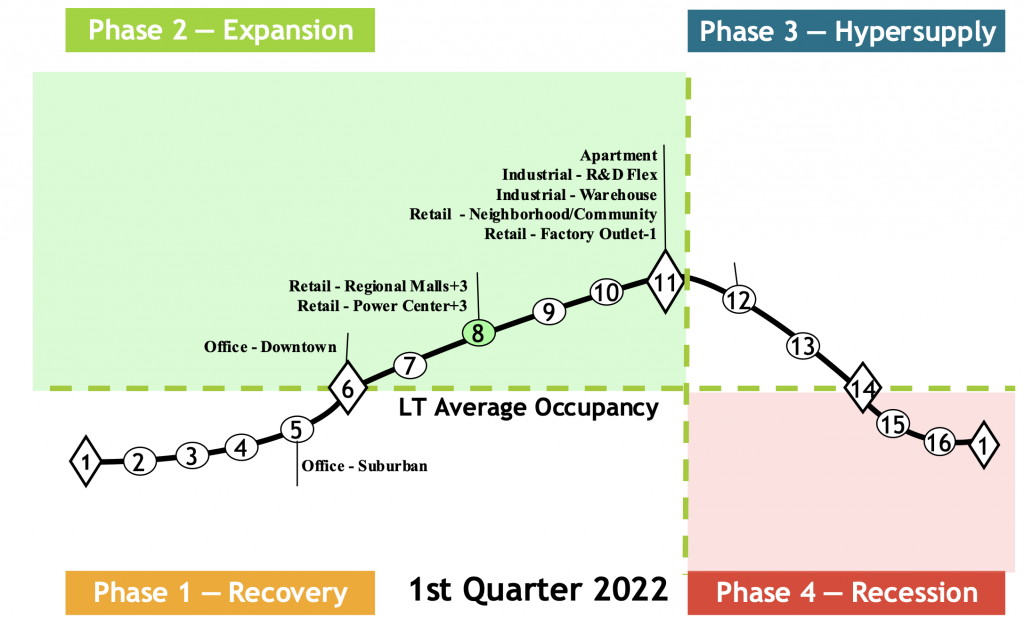

National property type cycle locations

The cycle monitor analyses occupancy movements in five property types in 54 MSAs. Market cycle analysis should enhance investment-decision capabilities for investors and operators. The five property type cycle charts summarise almost 300 individual models that analyse occupancy levels and rental growth rates to provide the foundation for long-term investment success. Commercial real estate markets are cyclical due to the lagged relationship between demand and supply for physical space. The long-term occupancy average is different for each market and each property type. Long-term occupancy average is a key factor in determining rental growth rates – a key factor that affects commercial real estate income and thus returns.

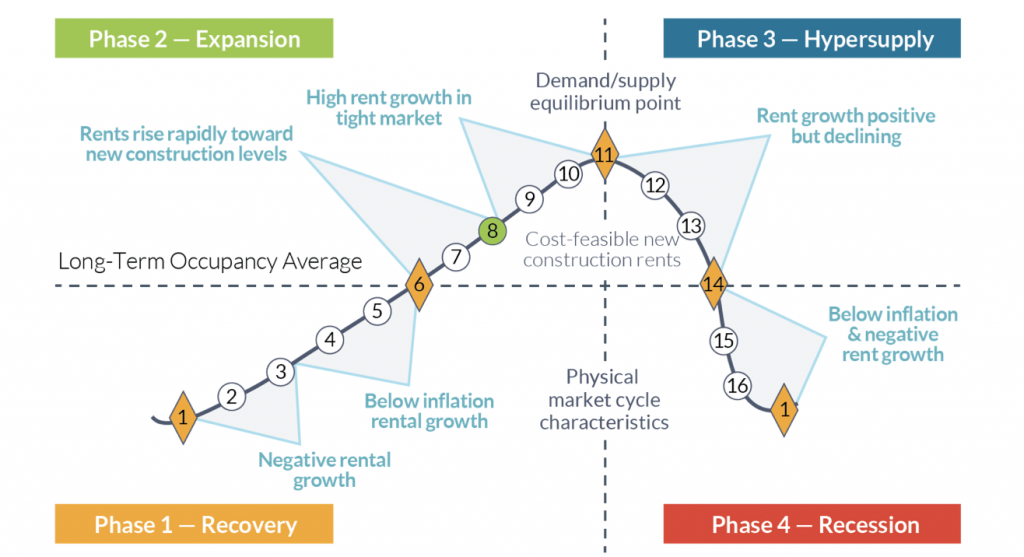

Market cycle quadrants

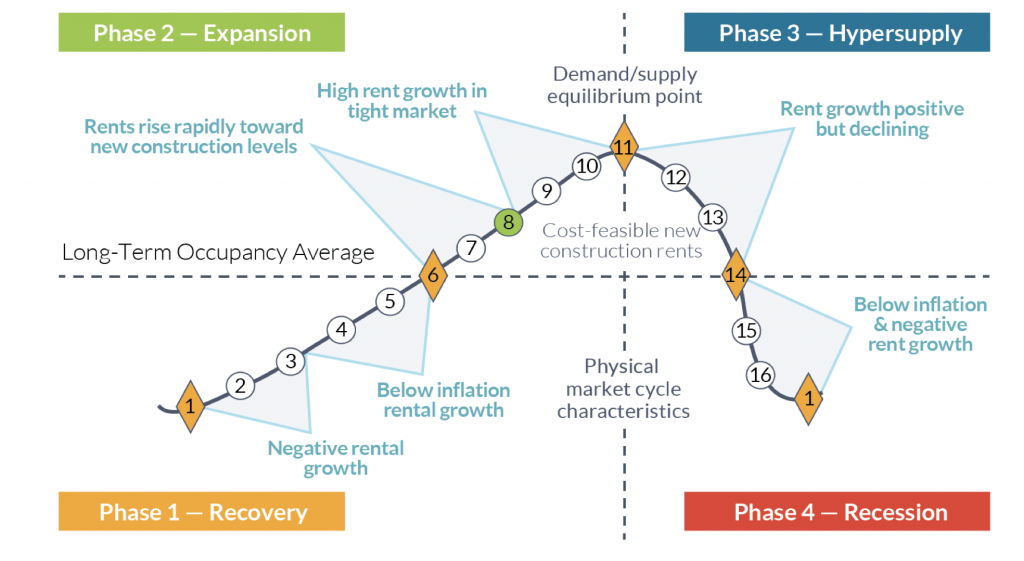

Rental growth rates can be characterised in different parts of the market cycle, as shown below.

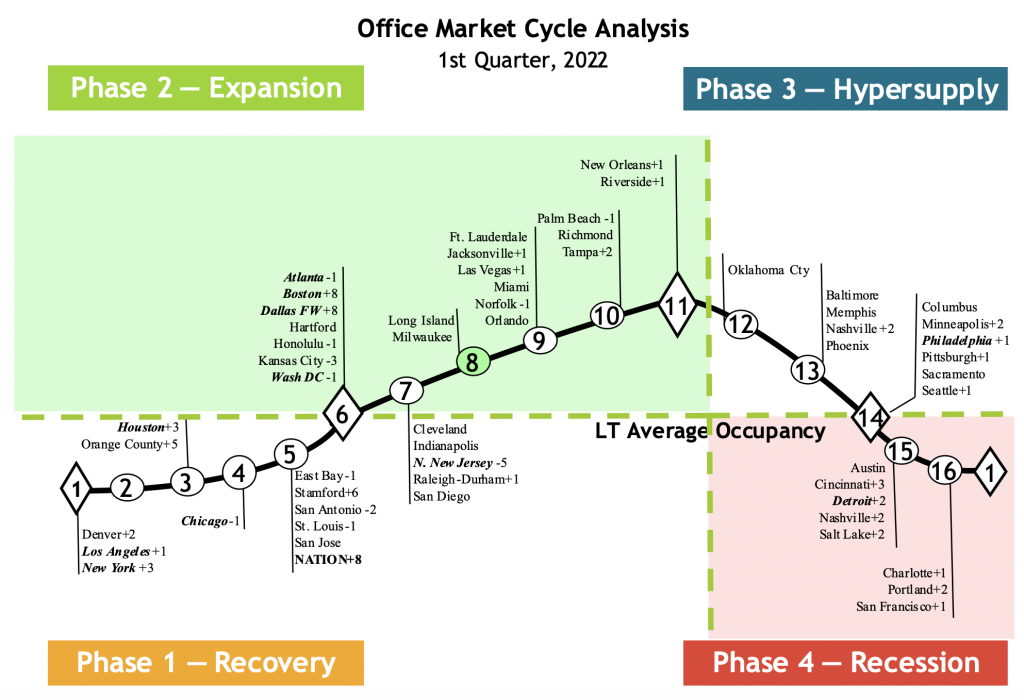

Office

The national office market occupancy level decreased 0.1% in 1Q22 and was down 0.2% year-over-year. However, demand picked up in many markets and the forecast now shows increasing occupancies in the future, moving many markets into the recovery and growth phase of the cycle. There have been many new large major employer headline leases to a provide positive outlook, but many markets saw firms with lease expirations taking less space than they had in the past. Our positive demand outlook comes from the continued strong US employment growth with 428,000 jobs created in April 2022. All levels of space quality have seen reasonable leasing activity in Q1, but renovations to attract employees back are booming. The high-cost gateway markets like New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles hit their cyclical bottoms, as migrations to second-tier markets continue. Average national asking rents improved 0.2% in 1Q22 but were down 0.7% year-over-year.

Note: The 11-largest office markets make up 50% of the total square footage of office space we monitor. Thus, the 11-largest office markets are in bold italic type to help distinguish how the weighted national average is affected.

Markets that have moved since the previous quarter are now shown with a + or – symbol next to the market name and the number of positions the market has moved is also shown, i.e., +1, +2 or -1, -2. Markets do not always go through smooth forward-cycle movements and can regress or move backward in their cycle position when occupancy levels reverse their usual direction. This can happen when the marginal rate of change in demand increases (or declines) faster than originally estimated or if supply growth is stronger (or weaker) than originally estimated.

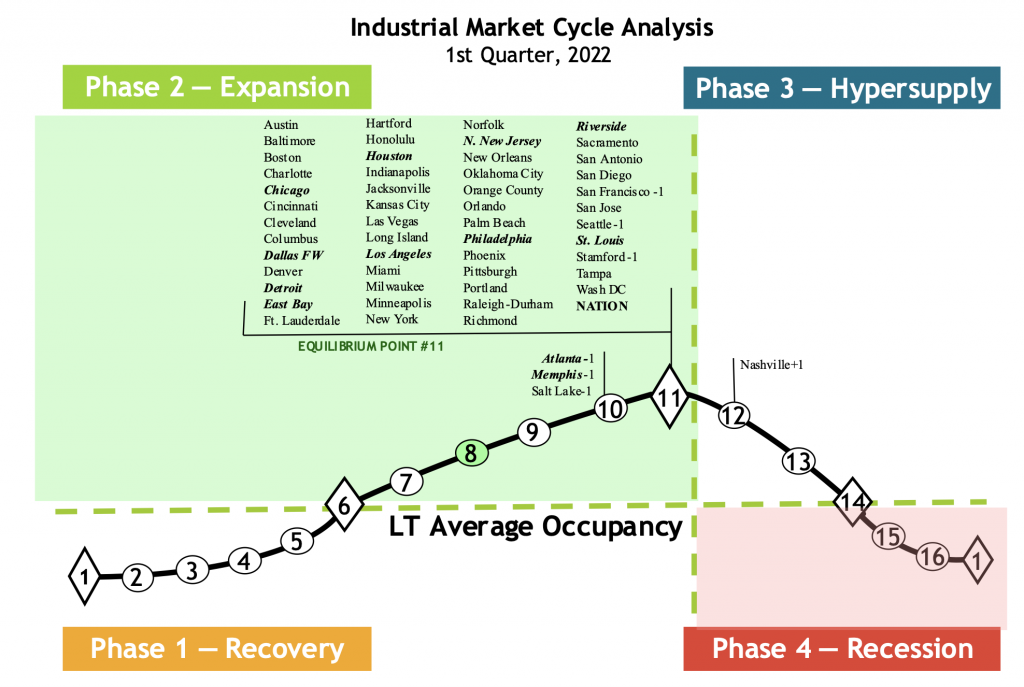

Industrial

Industrial occupancies increased 0.2% in 1Q22 and were up 1.3% year-over-year, pushing the historic high occupancy peak even higher! Strong demand from increasing e-commerce and brick-and-mortar retailers leasing more space motivated strong construction that should peak later in 2022. Industrial leasing growth leveled off in 1Q22 as there is not enough new space available to lease for the demand. Supply constraints should keep the market in balance for at least a year. Owners pushed rents up 0.2% in 1Q22, with annual rents being a 1.3% increase year-over-year.

Note: The 12-largest industrial markets make up 50% of the total square footage of industrial space we monitor. Thus, the 12-largest industrial markets are in bold italic type to help distinguish how the weighted national average is affected.

Markets that have moved since the previous quarter are now shown with a + or – symbol next to the market name and the number of positions the market has moved is also shown, i.e., +1, +2 or -1, -2. Markets do not always go through smooth forward-cycle movements and can regress or move backward in their cycle position when occupancy levels reverse their usual direction. This can happen when the marginal rate of change in demand increases (or declines) faster than originally estimated or if supply growth is stronger (or weaker) than originally estimated.

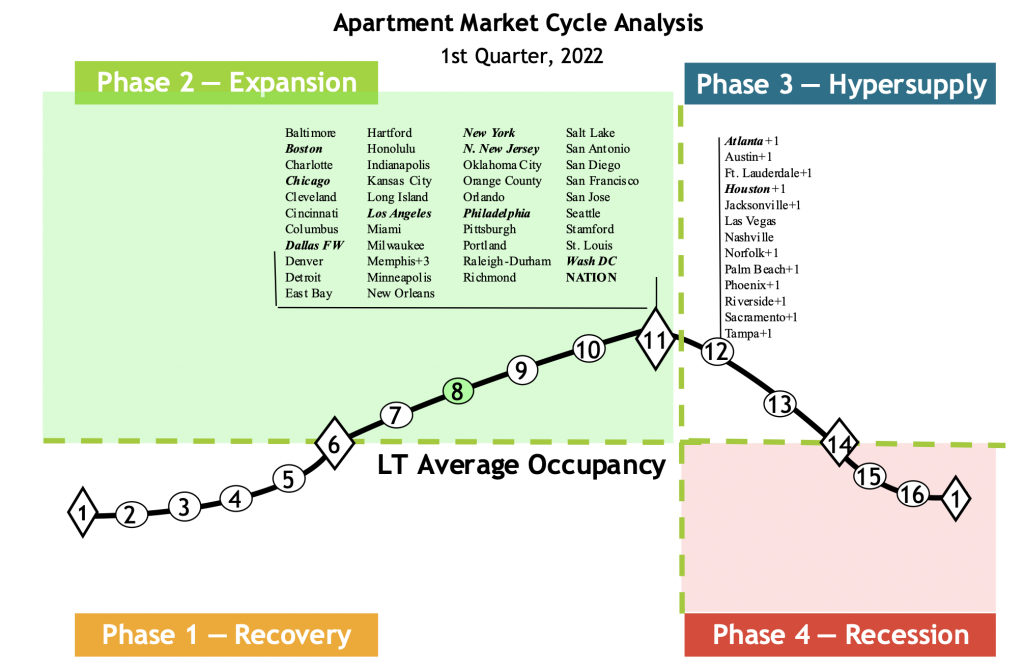

Apartment

The national apartment occupancy average declined 0.1% in 1Q22 but was up 1.2% year-over-year. Absorption of over 700,000 units in 2021 was double the national average over the last 5 years. Increased mortgage rates made it even more difficult for 1st time home buyers, keeping them in the rental market. Both CBD and suburban markets continued to experience strong leasing, as the U.S. is short over 4 million housing units (ownership and rental combined). The cycle report shows 11 markets that moved into the hypersupply phase as new completions jumped by 40% in 1Q22, created a minor oversupply in these markets. National average apartment asking rent growth was 2.5% in 1Q22 and rents were up 4.2% year-over-year.

Note: The 10-largest apartment markets make up 50% of the total square footage of multifamily space we monitor. Thus, the 10- largest apartment markets are in bold italic type to help distinguish how the weighted national average is affected.

Markets that have moved since the previous quarter are now shown with a + or – symbol next to the market name and the number of positions the market has moved is also shown, i.e., +1, +2 or -1, -2. Markets do not always go through smooth forward-cycle movements and can regress or move backward in their cycle position when occupancy levels reverse their usual direction. This can happen when the marginal rate of change in demand increases (or declines) faster than originally estimated or if supply growth is stronger (or weaker) than originally estimated.

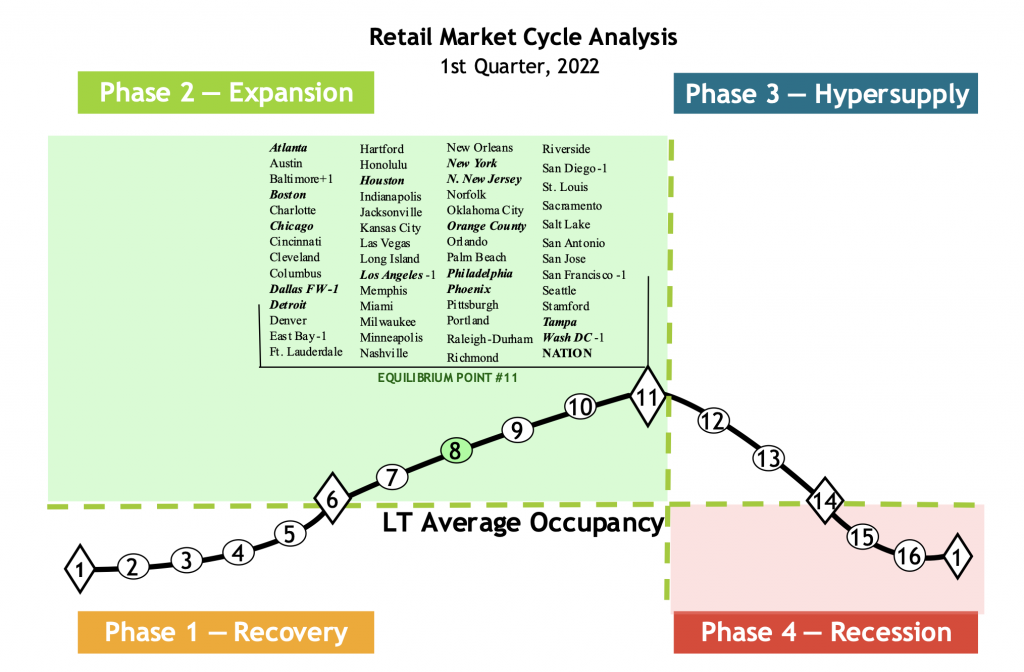

Retail

Retail occupancies were up 0.2% in 1Q22 and up 0.7% year-over-year. Active consumers with government Covid relief stimulus money drove retail sales to a record $378 billion. Demand for space created 63 MSF of new leases in 1Q22, which is only 6% below pre-pandemic levels. New completions were only 13 MSF of which 80% was pre-leased, and supply was further constrained by 7 MSF of retail demolitions. Higher quality retail is in highest demand. National average retail asking rents were up 0.6% for the quarter and were up 1.9% year-over-year.

Note: The 14-largest retail markets make up 50% of the total square footage of retail space we monitor. Thus, the 14-largest retail markets are in bold italic type to help distinguish how the weighted national average is affected.

Markets that have moved since the previous quarter are now shown with a + or – symbol next to the market name and the number of positions the market has moved is also shown, i.e., +1, +2 or -1, -2. Markets do not always go through smooth forward-cycle movements and can regress or move backward in their cycle position when occupancy levels reverse their usual direction. This can happen when the marginal rate of change in demand increases (or declines) faster than originally estimated or if supply growth is stronger (or weaker) than originally estimated.

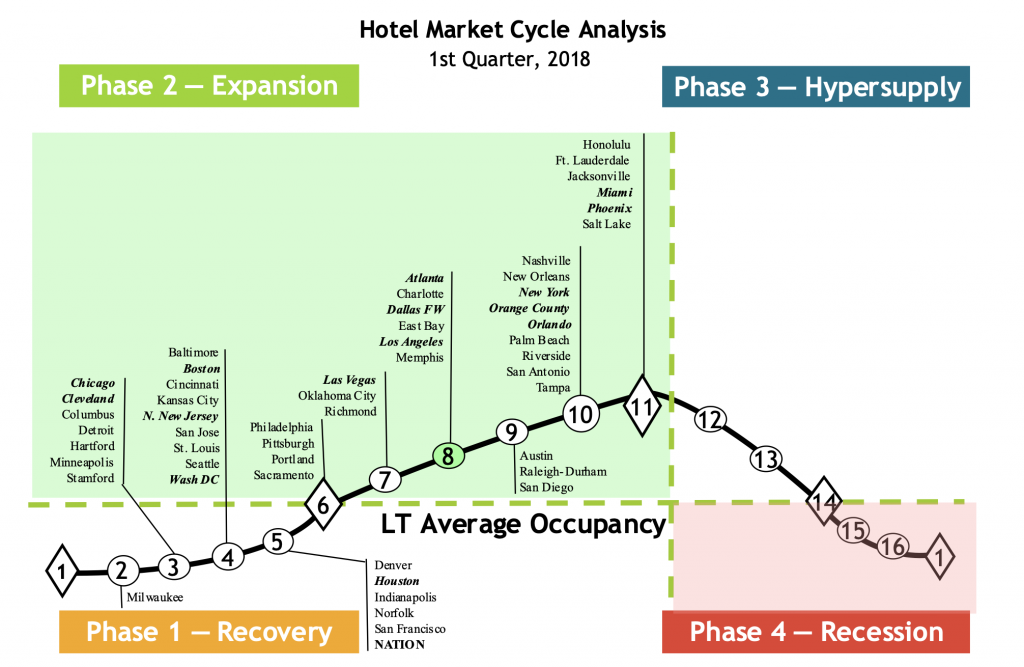

Hotel

Hotel occupancies were up 4.1% in 1Q22 and up 8.2% year-over-year. Leisure travel has resumed in full force with vacationers excited to use some of their travel money that built up over the last two years. The outlook is bright as demand looks good going forward (unless a recession actually happens). Business dominant markets are still recovering as both conference and business travel are recovering much slower than leisure travel. Hotels have decided to not give away rooms and have raised room rates. The Average Daily Rate (ADR) was up 9.3% for the quarter and up 31.1% year-over-year. National average Revenue Per Available Room RevPAR was up 30.3% for the quarter and up 52.9% year-over-year.

Note: The 14-largest hotel markets make up 50% of the total square footage of retail space we monitor. Thus, the 14-largest hotel markets are in bold italic type to help distinguish how the weighted national average is affected.

Markets that have moved since the previous quarter are now shown with a + or – symbol next to the market name and the number of positions the market has moved is also shown, i.e., +1, +2 or -1, -2. Markets do not always go through smooth forward-cycle movements and can regress or move backward in their cycle position when occupancy levels reverse their usual direction. This can happen when the marginal rate of change in demand increases (or declines) faster than originally estimated or if supply growth is stronger (or weaker) than originally estimated.

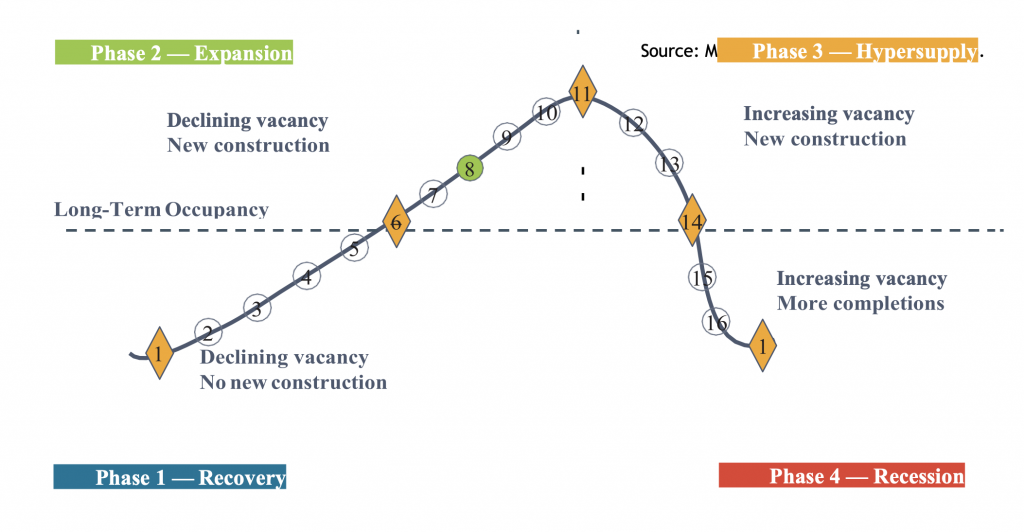

Market cycle analysis: explanation

Supply and demand interaction is important to understand. Starting in Recovery Phase I at the bottom of a cycle (see chart below), the marketplace is in a state of oversupply from either previous new construction or negative demand growth. At this bottom point, occupancy is at its trough. Typically, the market bottom occurs when the excess construction from the previous cycle stops. As the cycle bottom is passed, demand growth begins to slowly absorb the existing oversupply and supply growth is nonexistent or very low. As excess space is absorbed, vacancy rates fall, allowing rental rates in the market to stabilize and even begin to increase. As this recovery phase continues, positive expectations about the market allow landlords to increase rents at a slow pace (typically at or below inflation). Eventually, each local market reaches its long-term occupancy average, whereby rental growth is equal to inflation.

In Expansion Phase II, demand growth continues at increasing levels, creating a need for additional space. As vacancy rates fall below the long-term occupancy average, signaling that supply is tightening in the marketplace, rents begin to rise rapidly until they reach a cost- feasible level that allows new construction to commence. In this period of tight supply, rapid rental growth can be experienced, which some observers call “rent spikes.” (Some developers may also begin speculative construction in anticipation of cost-feasible rents if they are able to obtain financing). Once cost-feasible rents are achieved in the marketplace, demand growth is still ahead of supply growth — a lag in providing new space due to the time to construct. Long expansionary periods are possible and many historical real estate cycles show that the overall up- cycle is a slow, long-term uphill climb. As long as demand growth rates are higher than supply growth rates, vacancy rates should continue to fall. The cycle peak point is where demand and supply are growing at the same rate or equilibrium. Before equilibrium, demand grows faster than supply; after equilibrium, supply grows faster than demand.

Hypersupply Phase III of the real estate cycle commences after the peak / equilibrium point #11 — where demand growth equals supply growth. Most real estate participants do not recognize this peak / equilibrium’s passing, as occupancy rates are at their highest and well above long-term averages, a strong and tight market. During Phase III, supply growth is higher than demand growth (hypersupply), causing vacancy rates to rise back toward the long-term occupancy average. While there is no painful oversupply during this period, new supply completions compete for tenants in the marketplace. As more space is delivered to the market, rental growth slows. Eventually, market participants realize that the market has turned down and commitments to new construction should slow or stop. If new supply grows faster than demand once the long-term occupancy average is passed, the market falls into Phase IV.

Recession Phase IV begins as the market moves past the long-term occupancy average with high supply growth and low or negative demand growth. The extent of the market down-cycle is determined by the difference (excess) between the market supply growth and demand growth. Massive oversupply, coupled with negative demand growth (that started when the market passed through long-term occupancy average in 1984), sent most US office markets into the largest down-cycle ever experienced. During Phase IV, landlords realize that they could quickly lose market share if their rental rates are not competitive. As a result, they then lower rents to capture tenants, even if only to cover their buildings’ fixed expenses. Market liquidity is also low or nonexistent in this phase, as the bid–ask spread in property prices is too wide. The cycle eventually reaches bottom as new construction and completions cease, or as demand growth turns up and begins to grow at rates higher than that of new supply added to the marketplace.

This research currently monitors five property types in 54 major markets. We gather data from numerous sources to evaluate and forecast market movements. The market cycle model we developed looks at the interaction of supply and demand to estimate future vacancy and rental rates. Our individual market models are combined to create a national average model for all US markets. This model examines the current cycle locations for each property type and can be used for asset allocation and acquisition decisions.

Reprinted with permission from Denver University – Burns School of Real Estate & Construction Management.