Property and inflation.

My friend, colleague and fellow co-head of research, Kevin White, has spent the past few months quoting Mark Twain and telling me that, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes”. The reason for the quote is to reassure that, even in this period of high inflation, commercial property should continue to be a strongly performing asset class.

But to which period in history should we look? The most obvious perhaps are the 1970s or the 1990s, but why not others? Despite the overuse of war metaphors during the pandemic, the two world wars are probably not a good reference point, but what about the latter part of the 1940s?

In 1947, US inflation jumped to 20% as supply shortages, pent-up demand and the elimination of price controls led to a surge in inflation, particularly in food, fuel and consumer durables. After around two years, normalising supply chains and a mild recession saw price growth return to more modest levels.

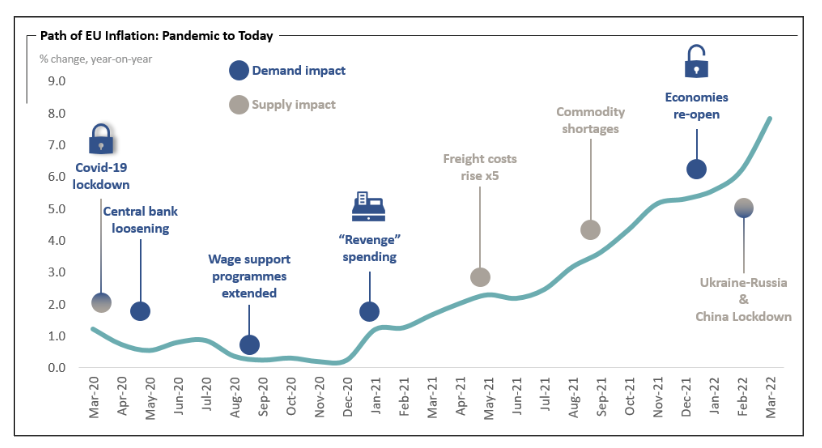

This sounds somewhat familiar. We didn’t see price controls, but supply-chain problems, pent-up demand, rising fuel and food prices are all issues we’re experiencing today. And, while I know it’s controversial to use the term temporary, I still expect inflation to moderate over the coming year.

I can’t back this up with data from the 1940s, but if this is the outlook for today’s inflationary period, I wouldn’t expect it to have a lasting impact on property performance.

But what if I’m wrong? What can history tell us about real estate in a world where inflation is not short-lived or the economic slowdown proves more aggressive than currently forecast?

The 1970s and early 80s, for example, suggests we shouldn’t be too worried. Despite recession, double-digit inflation and a Fed funds rate that hit 20%, both US housing and commercial real estate values grew at an annual rate of around 8%, providing returns above both equities and bonds.

This is all very good news. Real estate was doing what real estate is supposed to do – acting as an inflation hedge. But are the 1970s a good guide for today?

It’s true that this was a period of geopolitical risk, high energy prices and rising interest rates, but it was also a period that saw the ending of the gold standard, exceptional and sustained growth in the money supply, and a unionised workforce with much higher inflation expectations.

Perhaps the early 90s is a better comparison. An energy-rich nation invading its smaller neighbour, oil prices doubling in a short space of time, a short-lived jump in inflation, recession followed by an easing of monetary policy.

“By the end of 1992, prime London office rents were just half of what they were at the start of the decade”

Unlike the 1970s, property performed exceptionally poorly during this period. And while Donald Trump’s description of the early 90s being as bad as 1928 and worse than the financial crisis may not stand up to a fact check, many global cities saw prices collapse. By the end of 1992, prime London office rents were just half of what they were at the start of the decade.

In this case, history certainly didn’t rhyme. Why was the performance of the real estate sector so different? As ever, there are a myriad of reasons, but I would point to the simplest. Falling occupier demand at a time of exceptionally strong supply.

According to PMA estimates, in 1991, Central London saw almost one million square metres (10.8 million square feet) of new space delivered onto the market. Equivalent to building 18 of The Shard, an already elevated vacancy rate jumped to 21% by the end of the year. Given this backdrop, it’s no wonder real estate didn’t act as an inflation hedge – quite the reverse.

I take comfort when I compare this to today’s market. While we expect economic activity to slow, we see few signs of excess in both commercial property development and lending. Housing is in short supply, logistics vacancy is hitting new lows and even in the uncertain world of offices, available space is in line with history. Indeed, given relatively modest levels of construction, in cities such as Paris and London, Grade A offices continue to see rental growth.

Excluding the retail sector, which faces the challenges of both high vacancy and squeezed disposable incomes, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to think that real estate will once again provide an inflation hedge.

Over the coming year or so this should be most evident in continental Europe, given the widespread use of lease indexation, and seen more broadly over the medium term as higher prices – particularly construction costs – are passed on through to prime rents.

Given this backdrop, I’m still positive on the residential rental sector. Not only is there a lack of stock across most major markets, in the past we’ve also seen a close correlation between wage growth and residential rents. If inflation remains higher for longer, higher nominal wages, already rising strongly in the United States, could materialise in other developed markets.

There is a risk that if wage growth doesn’t follow, and households face a further squeeze, this could jeopardise our outlook. In general, I see a greater risk for non-essential spending, but it also strengthens the investment case for social and affordable housing, where residents are potentially less exposed to this period of stress.

Most importantly though, residential should continue to benefit from long-term structural changes that go well beyond the ups and downs of today’s economic cycle.

There is a good chance that, like many, my outlook for inflation over the next one or two years will prove incorrect. But as a real estate investor I can look further out, and here I remain confident that by the end of the decade the world will be older, more urban, with a continued desire to live in high quality, affordable housing.