It’s more than a case of semantics

Deglobalisation, as a concept, has been mentioned quite a bit recently (along with the topics of onshoring and nearshoring), but the evidence of it happening on a significant scale thus far is scant, at best. Instead, key economic pointers suggest that, rather than going into reverse, globalisation has taken a breather – a trend that is best described as ‘slowbalisation’.

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that real estate is intensely local and even small shifts in cross-border trends can have an outsized impact on specific local real estate markets (think Brexit relocations and the ramification that’s had on Dublin, Luxembourg, Paris and Frankfurt). So, a better way to gauge slowbalisation is by looking at the two main transmission mechanisms of slowing globalisation for real estate: capital flows and the supply chain of goods.

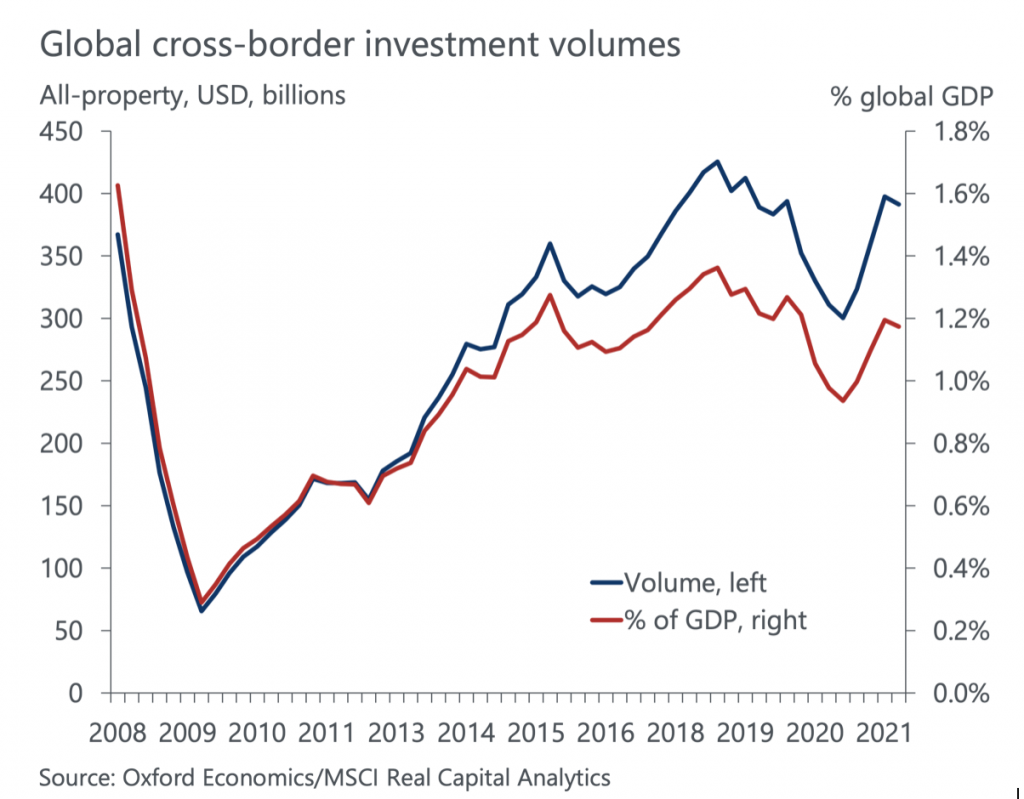

Real estate capital flows

There’s little evidence to suggest that deglobalisation is occurring for real estate capital flows, but slowbalisation has been with us since 2014-2015. Although global cross-border investment returned to strength in 2021, reaching a three-year high at just under $400bn and logging its second-best year since records began in 2008, the flow of capital as a share of GDP was below 2018-2019, continuing the stationary trend that’s been in place since 2014-2015 (see chart). Indeed, global cross-border investment as a share of total volumes was the same in Q4 2021 as in Q1 2014.

Looking at the UK, we see a similar picture, with the share of the UK commercial property market owned by overseas investors flattening out since 2017 and while that levelling could be due to idiosyncratic factors such as Brexit or the pandemic impact, it is consistent with the global trend.

More generally, in recent decades, there’s been an expansion of real estate market participants (sovereign wealth funds, endowment funds, investment banks, etc), with entrants from more geographically diverse locations. That trend has accompanied the development of new real estate investment vehicles and the wider availability of debt financing which has supported the globalisation of real estate. But acquisitions still tend to be dominated by domestic players, as is the case in Europe, with just five of the top 20 buyers since 2017 from non-European headquarters. All the same, caution needs to be applied when tracking cross-border capital flows in this way as they’re likely to miss the true source of funds, since a buyer headquartered in the US may raise capital from multiple global sources, for example.

The supply chain of goods

Less concrete evidence supports deglobalisation in terms of the flow of goods, particularly from supply-chain risk management improvements, such as shortening supply chains. This is tough to quantify using hard data and has mixed signals from surveys – indeed, a recent Oxford Economics global risk survey found only 12% of respondents improving supply-chain resilience by onshoring or nearshoring. Changes to global supply chains often take place at the margins and are due to redundancy rather than widespread geographic changes in activity, as firms seek out alternative suppliers closer to home, but still use lower-cost suppliers further away. There are simply too many cost advantages from global sourcing to completely abandon the globalisation in production.

For real estate, the examples stemming from a slowdown in the globalisation of goods production are often for specific reasons, such as enhancing national security, supporting strategic industries or managing supply-chain risk.

Enhancing economic or national security

A recent example is the US CHIPS Act, which has stimulated semiconductor investment, boosting manufacturing demand for certain parts of the US. In 2021, Samsung, Micron Technology Inc, Intel and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co all announced plans to either expand or develop new facilities in the US, increasing manufacturing demand around Austin and Phoenix.

More broadly, it’s likely that countries will engage in more strategic, targeted measures to limit economic ties and protect domestic sectors. Technology and the spread of knowledge across borders is a key area that states have and will likely continue to target. This technological decoupling can have a significant impact on long-term growth prospects and could be beneficial to source economies since the technology sector has meaningful spillovers for economic growth.

Supply-chain risk management

To manage the risk from supply-chain disruption in the wake of the pandemic and various geopolitical events (Brexit, US-China trade war, Ukraine-Russia war), firms have been looking to simplify supply chains (fewer links to manage delays and transportation costs), diversifying partners (companies and geographies), holding greater inventory (just-in-time to just-in-case), and reshoring or nearshoring activity. In some cases, this has helped to generate strong industrial leasing demand and reduce vacancy rates, particularly when it’s more cost effective to add warehousing space to alleviate higher transportation costs.

But wide-scale reshoring or nearshoring has not been observed to date. For example, a study in France by Trendeo found that between 2009 and 2020 there were only 144 cases of companies reshoring, compared with 469 cases of offshoring. There are multiple geographical, material and organisational constraints to reshoring that are tough to overcome – for example, reshoring production may have a limited effect since the raw materials or intermediate components required for production may not be available in the home country, requiring transportation regardless.

This point is substantiated by a 2021 survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in China, which suggests there’s little appetite among US companies to relocate, with only 14% of firms interested in relocation and just half of that figure having acted. Indeed, Asia was more popular as a relocation destination, suggesting a ‘China plus one’ strategy by US companies rather than a major shift in trade back to the country or region of the consumer.

Framework for investors to assess the risk of deglobalisation

While there’s little evidence for outright deglobalisation, there has been a slowdown in global real estate cross-border capital flows as a share of GDP and cases where onshoring/nearshoring activity impacted local property markets. As such, deglobalisation does present a downside risk. So, here’s a framework to help investors assess their risks:

a) The sensitivity of an asset and its occupiers to changes in national security or changes in the stance towards industries of strategic priority to the economy.

b) Specifically, the exposure of multinational companies operating in overseas economies to sensitive technologies or cutting-edge knowledge sharing.

c) The position of an industrial asset in a global supply chain relative to its value-add – could it be a risk from the standpoint of supply chain redundancy?

d) Portfolio weighting to economies that have been past beneficiaries of globalisation, such as export-oriented emerging economies, as these are likely to see a greater impact.