This morning’s report from the Resolution Foundation on the employment surge since the financial crisis is a healthy rejoinder to those who are pessimistic about the state of the British economy.

The Conservatives make great play of their record on job creation, and well they might given that there are 2.7 million more people in work now than in 2008 and the headline employment rate has never been higher.

To listen to some, not least Jeremy Corbyn, all the jobs created since the coalition government came to power are insecure, part-time, gig economy roles, probably in the service of some faceless Californian venture capitalist.

Leaders of the Opposition are entitled to paint as dramatic a picture as they like of the Government’s failings, but today’s stats suggest Corbyn is just plain wrong. Far from just being low-paid jobs the trend since the financial crisis has been one of “occupational upgrading” — though Clarke and Cominetti point out that the growth in better paid jobs actually goes back to the turn of the millennium.

The authors also note that “record employment has been progressive. Rising employment has helped support household incomes over the past seven years, offsetting, and in part representing a response to, a significant loss of earnings power and cuts in state support”.

And far from a London-centric boom that has chiefly benefited migrants, researchers Stephen Clarke and Nye Cominetti find that employment growth has happened all over the UK, with areas of low employment starting to catch up. If London has put on more jobs, it’s because the capital’s population has risen significantly over that time, not because it has a particularly high job creation rate relative to the rest of the country.

Ah, but it’s all been to migrants — not quite. While those born outside the UK do account for two thirds of the new jobs since 2008, that has had little to no impact on the prospects of those born in the UK, whose rate of employment has gone up at the same time. This is more or less the same conclusion that the Migration Advisory Committee came to in its report last summer.

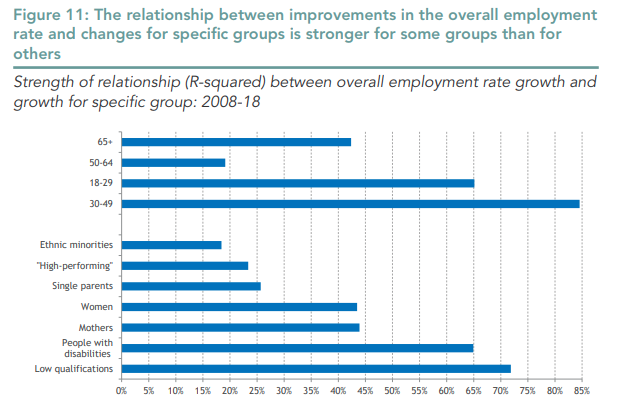

Those with few qualifications have been among the biggest beneficiaries of the surge in employment. In fact, almost half of the net increase in employment over the last eight years has been from the least well-qualified third of the working-age population.

None of this is cause for complacency — Resolution warns that the picture is bleaker for younger workers and, more broadly, automation will bring changes we are unlikely to foresee, let alone plan for.

What’s more, employment among certain groups of people — the disabled, for instance — still lag behind the national average, although the disabled employment rate has gone up by an impressive 6.4 percentage points since 2008 (compared to 2.9 per cent for non-disabled workers).

As we have pointed out before on CapX, it’s estimated that increasing the proportion of disabled people in work — a structural, rather than a cyclical issue — would bring the Exchequer an extra £12bn in taxes by 2030.