Originally published March 2022.

It’s been five years since Neil Turner stepped down from a senior real estate position in the City. He’s been spending time writing fiction, enjoying the Suffolk countryside and the occasional visit back to central London. One recent trip formed the basis of his first article for us that appeared on 17 January. This is a follow-up piece about the alarming impact that the timing of investment returns can have on our pension pots.

When it comes to our pensions, what are the investment risks we should really worry about?

Volatility of returns?

Level of real investment returns?

Probably both, I hear you say, and, of course, I’d agree.

But what about the order in which investment returns occur through time?

A little esoteric, you might reasonably argue, even for a man sitting in the heart of East Anglia. However, for those of us with defined contribution (DC) pension pots (and this is a rapidly growing cohort, by the way) the answer to this question turns out to be critical to the level of our pension pots and, as a result, the quality of our retirements.

I’m not sure why the asset management industry isn’t more focused on this. Traditionally, of course, it has spent most of its time thinking about time-weighted rates of return (where the return in each period is given equal weight) as opposed to money-weighted returns (where each return is weighted by the amount of money it acts on). Historically, this was fine, given the dominance of (collective) defined benefit (DB) pension plans.

Although time-weighted returns are simple and convenient, they are irrelevant for the world of DC pension plans; and this is why.

Unlike in a traditional collective DB pension scheme, an individual’s DC pension pot starts at zero and then builds up during the accumulation phase, hopefully reaching a maximum at the point of retirement. While investment returns in the early years of the scheme will have some impact on the final value of the pot, it will be relatively modest, because the value of the accumulated contributions is initially quite small. By contrast, the impact of investment returns in the decade prior to retirement is critical, because at that point the returns are acting on a much larger sum of money.

And it’s not just our pensions. Every investment vehicle we use these days start from nothing and then grow by a combination of the contributions we make and the investment performance we enjoy (endure). So, the fact that our ISA portfolios are running alongside our DC pensions actually compounds this ‘timing’ risk.

Intuitively I’m sure this makes sense to most readers. “But it’s at the margin, surely?” I hear you ask. It can’t have too much of an impact, otherwise the industry would be shouting from the rooftops, right? Wrong.

Have a look at the following, real-life example.

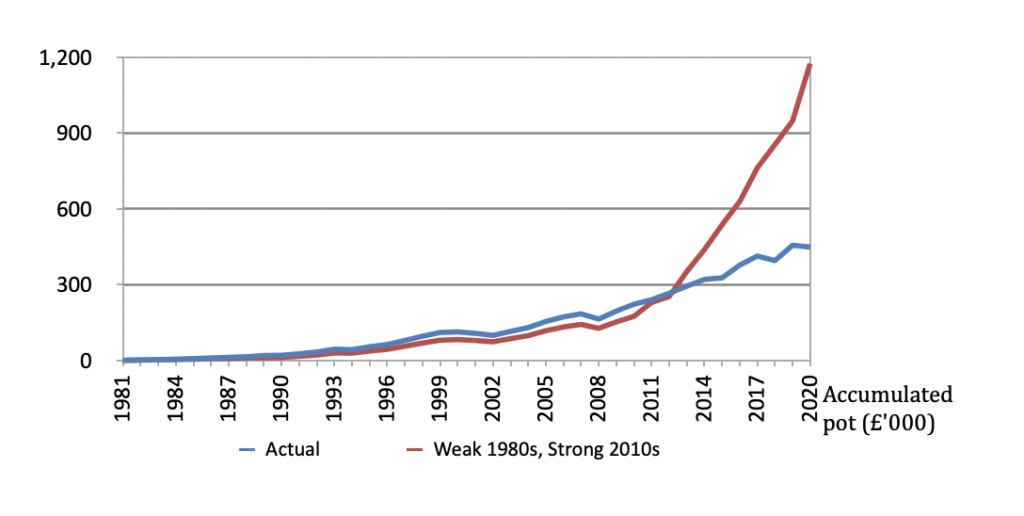

The base case shows the value of a hypothetical pension pot for someone who took out a DC personal pension on 1 January 1980 and retired 40 years later on 31 December 2020. The calculation assumes for the sake of simplicity that the individual had average earnings, that they routinely saved 10% of their income and that they maintained a constant 60:40 allocation between equities and gilts. By the time they retired they had a pension pot of £449,164, equal to 10.5x their annual salary in 2020 and their pension contributions had a money-weighted (IRR) of 7.7%.

The orange line shows an alternative scenario of what might have happened had there been a bull market in equities and gilts in the critical period leading up to retirement. The alternative scenario was created by simply switching the relatively poor returns of the 2010s with the particularly strong returns of the 1980s. The switch has no impact on compound annual total returns over 40 years measured on a time-weighted basis, because they ignore the amount of capital invested (the norm for DB pension funds). However, the switch has a dramatic impact on the final value of a DC pension pot, because the strong returns in the final decade before retirement were acting on a much larger sum of money.

In the alternative scenario, the final value of the pot is £1,175,312, equal to 27x the individual’s salary in 2020 and the money-weighted (IRR) on their contributions is 11.8%. In short, therefore, the final value of a DC pension pot is very path-dependent.

On the basis that only a few (very over-confident) people claim to be able to predict what the level of investment returns will be in the future, and that no one (at least to my knowledge) has dreamed of being sufficiently arrogant to foresee the precise order of these returns, what are DC investors to do?

Two things are paramount. First, save regularly and build diversified portfolios so that you can withstand a variety of outcomes. Second, we all need to think long and hard before crystallising our retirement portfolio at any single point in time. Fortunately, the new-found pension freedoms we now enjoy allow us to do just that and the next article will outline the options available.

I should also declare (reluctantly) that I am just about to turn 54. Therefore, I have the option of liquidating my entire DC pension pot in one go in 12 months’ time. What is a man to do?