Why low bond yields may mean you need to rethink your portfolio construction.

The future looks even more uncertain than usual. Normally uncertainty translates into lower asset prices. But not this time. And with the prices of all assets buoyed by abundant liquidity, we fear a traditional ‘diversified’ portfolio is not going to be much protection in the next market convulsion.

In particular, we believe that conventional bonds will provide neither acceptable returns in good times, nor much protection in a downturn.

This will be a shocking contrast to the last 40 years. Interest and inflation rates have been falling steadily since 1981 (according to Bloomberg data). The result has been that an investor combining equities and bonds has received excellent returns from both. Better still, when the equities fell, the automatic response of central banks has been to cut interest rates. This conveniently boosted the bonds just when the equities were suffering. The result was that the risk-adjusted returns, the returns adjusted for sleepless nights, from a traditional portfolio containing both assets was particularly attractive.

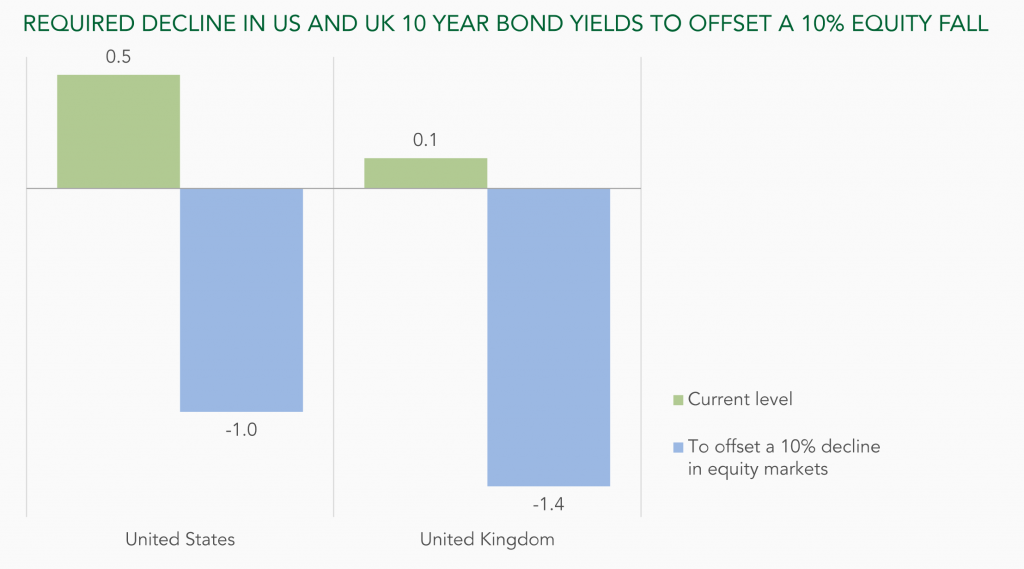

The chart demonstrates that bonds are very unlikely to do this job in the future.

What drives the price of a bond up is when the yield, the interest rate paid compared with the bond price, goes down. But yields are already about as low as they have ever been. The chart shows the level the yield would need to fall to for the bond part of a traditional balanced portfolio combining 40% bonds with 60% equities, to offset a mere 10% fall in the equities.

It shows that the ten-year US government bond yield would need to fall to -0.8% and the ten-year UK yield to -1.3% to do the job. It is true that the Bank of England has talked about negative interest rates. But you have to believe that they will go deep into negative territory, ignoring all the problems that would cause to the banking sector and to the economy, to imagine that investors would continue buying bonds with yields so negative.

That means bonds cannot effectively

protect an equity portfolio… and they offer

a lot more risk than potential reward

And these are yields on conventional bonds, so represent the returns before taking inflation into account. Inflation is unusually depressed, but positive even now. If, as we expect, the scale and scope of government spending marks the beginning of a new more inflationary era, then these negative nominal returns could be even less appetising. Deducting the average long-term inflation rate would mean accepting -4.3% pa after inflation in the US and -6.6% in the UK. Only inflation-linked bonds are attractive in these conditions.

We cannot see investors accepting this. That means bonds cannot effectively protect an equity portfolio. It also means they offer a lot more risk than potential reward.

Some people have turned to corporate bonds for a bit more yield. But this has compressed their risk premiums to levels that, again, do not compensate for the extra risk, making them the opposite of protective.

Others have turned to gold. And gold has an important role to play as a hedge against a loss of faith in paper money. But, as March showed, now it has been drawn into the liquidity party, it could be at risk when that liquidity recedes.

So, if conventional assets and traditional diversified portfolios cannot provide the protection required to keep portfolios safe in an uncertain world, what can? At Ruffer we accept that protection now must be paid for. And we believe that our credit and volatility protections can deliver performance that will effectively offset damage to our equities when the next dislocation comes. We consider that it is only these less conventional protections that will enable us to deliver continued growth in our portfolios, whatever is going on in the markets.

This article was originally published by Ruffer.