When I moved to London from abroad I was quite scared; not of all the difficult British accents, the sweaty tube or the doubtful love for vinegar. No… I was scared of the rental prices.

How is it normal to pay £1800 per month for outdated one-bedroom apartments with some suspicious leakage marks on the ceiling? And they were not even located in the hip Soho district or the fancy area of Chelsea. Being used to the Euro, I initially converted everything to my own currency. Surely, €2150 for a one-bed was too much. It felt as if something was not quite right.

Complaining about housing costs seems to have become an almost universal thing now; the cost of living crisis and people being pushed out of the cities by high prices and rogue landlords have all been in the news. It has made me wonder whether people have always complained about high rents or if the situation has actually gotten worse over time. How bad is it really?

It’s without question that rents in large European cities follow an upward trend. However, wages have been growing faster than market rents in most of them over the last five years, according to Green Street.

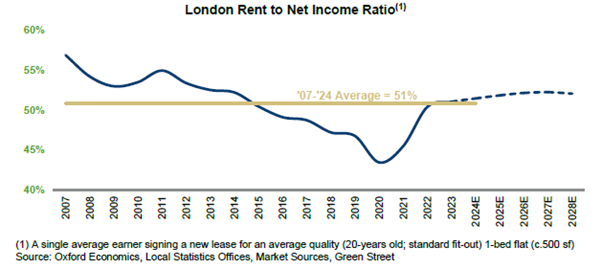

The large cities in the UK form, however, some of the exceptions: market rents have increased faster than wages since 2020. An average single earner now spends roughly 51% of his or her income on the rent of a one-bed in London. Rental affordability has definitely worsened over the last three years but is now at the long-term average. The situation seems even better now than it was ten to fifteen years ago. Of course this is related to a variety of factors such as Brexit, COVID and the owner-occupier market. But could it be that there is indeed somewhat of a discrepancy between reality and what people experience? In other words: are we complaining too much?

The answer to that question depends on whom you’re asking. The average rent-to-income ratio being 51% in London, means that many households are paying an even larger share of their income on rent. Not all salaries can keep up with rent increases and pay rises are not equal for all economic sectors. Therefore, certain living areas have gotten out of reach for people with lower- and middle-incomes. As cities are expanding, people with jobs that are important for society―such as teachers, nurses and policemen―are being pushed out. Such employees can’t work from home in cheaper areas either. It’s worrisome that the UK has the highest homelessness rate in the developed world and that its number of homeless households has more than doubled between 2010 and 2023, according to OECD data. It is then no surprise that the costs of living were the number one issue for voters during the latest elections.

There is, however, another side of the coin. The economic activity in a city such as London generates jobs with high or increasing salaries. This keeps drawing people in. Having access to all that economic activity plus everything else that a large city can offer you, might make it just worth it to spend 51% (or even more) of your income on rent.

However, we often seem to forget this, which might have to do with human psychology. We are prone to the cognitive bias of loss aversion. For example, the disappointment of losing a £50 note from your wallet affects your sentiment more than the joy of finding the same note on the street. Perhaps it works in the same way with renting. An increase in rent might be felt more than a proportional increase in income. Even when renting in a big city allows you to have a higher paid job in the first place. London’s population grew by a 100,000 last year alone, so it’s not hard to understand why rents keep rising over time. Space is just limited, and you can’t produce more of it. This is why social- and mid-segment rental housing is essential for liveable cities. It serves as a safety net for households with incomes that are not rising as quickly. For the other households, the situation might not be as bad as we think. Even when you only have 49% of your income left after paying your rent. Did this leave your wallet half full or half empty?