Much has been written in the Spanish press recently about the Valle de Los Caidos (the Valley of the Fallen), the monument to those who died in the Spanish Civil War (1936-9) which is a one hour drive north of Madrid near the Escatorial Palace, Philip II’s summer residence. It is built from the same austere grey granite as the Escatorial, during General Franco’s rule of Spain (Franco ruled from 1939-75) and he himself is buried there along with J A Primo de Rivera, who was the founder of the Falange (the Spanish fascist movement).

Monument at Valle de Los Caidos (Valley of the Fallen), near Madrid, built 1940 to 1959 (photograph by author)

The site is in the hills and there is a more alpine feel to the climate here which is why Phillip II escaped to this region during Madrid’s hot summers. The monument consists of a very tall imposing stone cross under which lies a crypt dug deep into the hillside. The monument conforms to most people’s idea of fascist architecture. It is monumental, imposing, solid, symmetrical, austerely detailed and overbearing in both scale and proportion. The crypt is dug a staggering 300 meters into the hillside and is impressive both in its size and in the kitsch way one would expect of a building commissioned by a totalitarian regime. The individual is diminished and the state is aggrandised by the strength of the building which overpowers the observer.

The Crypt at Valle de Los Caidos (Valley of the Fallen) containing General Franco’s tomb (photograph by author)

The recent uproar about the Valle de Los Caidos has been raised by the families of those who died and fought for the Republican cause and who are buried here. The vast majority of the 30,000 dead buried here fought on the Nationalist side. It seems that the government has agreed to disinter the Republican dead and rebury them elsewhere but is actually unable to find the funds to do so. There is also a movement to move Franco’s body elsewhere as he actually did not die during the war. Controversially, many Republican prisoners were forced to construct the monument and certainly a number of them died during the construction although the actual number is disputed by both sides.

My friendly taxi driver told me that his grandfather was a doctor in Madrid and fought for the Republican side as Madrid was controlled by the Republican government. His brother, who was a soldier, lived in Zaragoza and so fought for the Nationalists. Some did try to change sides but it was a risky business and those who were caught were executed (on both sides). Furthermore, independence movements such as Basque Nationalism played a confusing role. However, time and again I have heard of families split horribly like this.

We were visiting Madrid to see my wife’s former housekeeper/nanny, aged 94. I always wondered on what side the sympathies of this charming lady lay during the conflict. She said that she could not support the Republic as they desecrated the churches (over 6,800 priests were murdered during this brief but vicious war) and besides she was from Zaragoza which was Nationalist. Often it was geographical chance that determined which side one fought for and often two members of the same family fought on opposite sides.

However, I am interested to see how architects in Spain responded to the great twentieth century ideological battle between communism and fascism. Generally it is true that the Republic attracted ‘avant-garde’ artists and architects as it perceived the avant-garde as being synonymous with progress. And the rostrum of artists associated with the Republic is impressive; Alexander Calder, Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Salvador Dali, Juan Miro, Pablo Picasso and Man Ray for example. The list of architects is less well known but includes the GATPAC group, founded by Josep Lluis Sert and L G Soto amongst others. Much of what had been built by the Republic in Madrid before the civil war was destroyed during it. Madrid still suffers from this and has a feeling of a city left behind architecturally. There is really very little that excites and part of the reason for this is that the country’s isolation after the Second World War and its poverty, as a result of its isolation, did not encourage new design.

After Franco’s death there have been a few attempts to drag Madrid back into the modern world. Herzog de Meuron’s Caixaforum displays an impressive cantilever and some of Raphael Moneo’s buildings are well designed but hardly excite. There aren’t even many interesting examples of totalitarian architecture as there are in Rome, for example. Madrid, with its less grand, Paris like boulevards, is on the whole attractive but rather insipid architecturally.

Barcelona however, by contrast, seems to have captured much of the dynamic art and architecture that has bypassed Madrid. Barcelona is an energetic industrial city, much of it designed in the 19th century on a grid system except for the one road that cuts diagonally across the grid. Corners are chamfered so crossings have a more open feel. However, most building plots are the same size as they conform to the grid plan. As a result, the conundrum for most architects and their clients was how to differentiate themselves from their neighbour. This was resolved by highly designed, one off, often very idiosyncratic and slightly vulgar facades that expressed the owner’s wealth and the architect’s preference for the latest neo baroque or art nouveau fashion in decoration. It is the only city where Antonio Gaudí can be imagined as a natural product of this extreme and competitive context. Gaudí, I personally find difficult to like, but in the context of Barcelona I can understand him. And Gaudí’s great gift to the city was to say to future generations of architects ‘Look, I have had a bit of fun, why don’t you?’ When an architect receives a commission in Barcelona there is always in the back of his or her mind, the thought of being compared to Gaudí and this nudges him or her to push the boat out a little further. As a result Barcelona is showered with fun and exciting new architecture.

Barcelona Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe 1928 – 9

It is also the site of one of the great and truly iconic (to use an overused term) pieces of modern design – the Barcelona Pavilion designed by Mies van der Rohe in 1928-9 and built as the German pavilion for the World Exposition held in Barcelona in 1929. It was a temporary pavilion, without exhibits and meant merely as a place to walk through. It was to showcase the new German Weimar Republic and was built before the National Socialist’s rise to power in Germany. This was before the Second Spanish Republic which lasted from 1933 to1939. However, it had a short life and was torn down in 1930; but was then reconstructed between 1986 and 1989, so that what you see today is a meticulous reconstruction. It is genuinely a complete work of art and architecture and stands in wonderful contrast to its host city. Mies reacted to Barcelona, by not trying to compete with Gaudi on his terms but, in fact, by going in the complete opposite direction. It is through the manipulation of free floating walls and roofs, glass planes and richly veined slabs of marble and selective positioning of furniture (of his own design) that he manages to create the very first complete and self-consciously minimalist space. The building seems to inspire the inhabitant to have solely elevated thoughts and one sort of floats around all day on some imaginary elevated plane after visiting it. It is rare that I do not cry when I listen to a Chopin Nocturne. But equally rarely am I moved by architecture in the same way that I am by music. However, the Barcelona Pavilion is one of those exceptions; and it is a building that genuinely moved me the first time I saw it. However, let us turn to Mies’s motivations for designing this building.

In architecture or art, generally, when the term chameleonic is used, it is used pejoratively. In contrast, when the words ‘singular’ or ‘with integrity’ are used, they usually connote some positive association and are deemed words of praise. It is interesting to note that Mies took his mother’s name ‘Rohe’ and added the aristocratic Dutch prefix ‘van der’ demonstrating an early propensity to massage his own identity. Indeed his early career, before he went to America in 1938, where he had such huge success, was more chameleonic than has generally been supposed and certainly more than he would have wished to be known. In 1926, Mies designed the monument in Berlin to the November Revolution (torn down by the National Socialists nine years later). It was a sort of elongated, cubist red brick gravestone for the Communist martyrs, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg amongst others, who were executed against a brick wall during the 1918 communist uprising in Berlin.

Monument to the November Revolution in Berlin by Mies van der Rohe, 1926 and torn down in 1935.

Mies also designed and built a rather dull private double house of brick for two German industrialists, Hermann Lange and Josef Esters, in the town of Krefeld near the German/Dutch border between 1927 and 1930. He rarely talked about this building in his later life. However, he once did say that ‘I wanted to make this house much more in glass, but the client did not like that. I had great trouble.’ This project has only come to light quite recently and it has now been turned into a Museum. I presume that he was slightly embarrassed by it. It certainly does not have the conviction of his later work and perhaps he was still in the process of working out his ideas. But the reasons for his rejection of this early building may have been part of a post rationalization of his personal narrative rather than the restrictions placed on him by the conventional brief of a bourgeois industrialist’s home.

Between 1928 and 1930 he built and collaborated with the interior designer Lilly Reich on the Villa Tugendhat in Brno, Czechoslovakia. This was much more expressive and successful. It used wonderfully rich materials such as onyx which compensated for the banning of decoration and paintings within the house, a rule which he imposed on his clients. (It seems that he was having greater success at restricting the input of his clients!) The house was built of reinforced concrete and had a wonderful floor to ceiling glass facade that slipped into a crack in the floor at the touch of a button. Inevitably, it was extremely expensive as even the furniture was designed by him, but it was the first commission in which he really started to show both his design aesthetic and talent. Sadly, the villa’s life was short lived as the Tugendhats were forced to flee to Switzerland and the villa was seized by the gestapo in 1939.

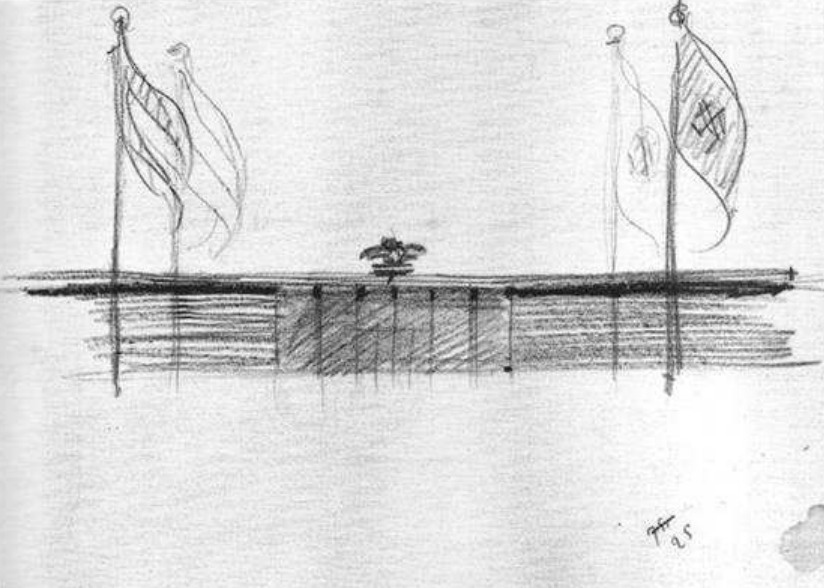

Later, in 1934, Mies received his only commission from the National Socialists for the design of the Deutsches Volk, Deutsches Arbeit (German People, German Work) exhibition in Belgium. Also in 1934 Mies won a competition to design the German pavilion at the 1935 Brussels Universal and International Exposition which was never built for economic reasons. However, the sketch (beautifully drafted by the master, for he was an excellent draftsman) clearly shows a reworking of the Barcelona pavilion, this time symmetrical and embellished with a German eagle above the entrance and flags, adorned with swastikas, on flagpoles flanking the head on approach

Sketch for the German Pavilion at the 1935 Brussels Universal and International Exposition, Mies van der Rohe. Note the swastikas drawn onto the flags and the centrally placed German eagle.

It seems that Mies would work for anyone who would give him a commission and his lack of political principals (and indeed collusion with some disreputable clients) was suppressed later when his career took off after the Second World War in the United States. Part of the suppression of this guilty history was possibly down to Philip Johnson, his great promoter at the Museum of Modern Art, who probably didn’t want Mies’s early years to be too closely scrutinised just in case the spotlight was turned back on him. Johnson, notoriously, was a great admirer of National Socialism in its early years, a fact that was later conveniently forgotten by him (for he was perhaps the greatest architectural chameleon of all). Also, Mies’s promotion to head up the Bauhaus school, after the more radical Hannes Meyer and at the suggestion of Walter Gropius, may have had something to do with the recognition by the Nazis that he was indifferent to politics.

In contrast to Mies was the less well known Josep Lluis Sert. Sert seems to have taken a more principled stand against Nationalism and certainly did not collude. He was born and trained in Barcelona and was the nephew of the painter J M Sert, a friend of Salvador Dali. In 1929 he lived in Paris and worked for Le Corbusier (receiving no payment for his efforts). During the 1930s he co-founded the GATPAC (Group of Catalan Artists and Technicians for the Progress of Contemporary Architecture) which became the Spanish branch of the influential CIAM (Congres International d’Architecture Moderne). From 1932 to 1937 he worked quietly on private residences and the masterplan for Barcelona, amongst other things. However, during most of the Spanish Civil War between 1937 and 1939 he lived in Paris. While in Paris he designed the Spanish Republic’s Pavilion at the World’s Fair, the Paris Exposition of 1937. Curiously, the Spanish Pavilion was built right next to the German Pavilion. Germany, through its Condor Legion of the Luftwaffe that had been lent to the Spanish Nationalists, had just bombed Guernica, the town in the Basque country that contained an important munitions factory for the Republic. Sert was a great admirer of contemporary artists, befriended many of them during his time in Paris and so called on them to fill his pavilion with works of art. Picasso, Miro and Calder all contributed pieces to the pavilion, but the main focus of attraction was Picasso’s giant canvas ‘Guernica’. Picasso’s painting was a powerful statement and illustrated the horrors, pain and atrocities of war through the depiction of a bullfight. In particular, it pointed the finger at the Nationalists for such a brutal campaign that killed so many innocent women and children. Guernica was offered after the Exposition to Spain but Picasso put a condition on the sale. The condition was that Spain be a Republic. Finally, in 1996, Guernica returned to Spain and is now housed in the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid.

Spanish Republic’s Pavilion at the World’s Fair, the Paris Exposition, 1937 by Josep Lluis Sert which contained ‘Guernica’ by Picasso

Sert moved to America after the Second World War where he had a successful career. Initially he was a visiting professor at Yale and then later he became Dean of the Graduate School of Design at Harvard, succeeding Walter Gropius. I have been told by a former student of his at Harvard that he was feared for his autocratic manner. However, he did succeed in designing and building numerous buildings in the Boston area, many of which sadly were not as distinguished as his early years had promised. His buildings at Harvard and Boston Universities just don’t fit with the harsh northern climate and tended towards the cold and dreary, with large expanses of poured concrete. On the other hand his buildings in Europe had a definite charm. The Foundation Maeght was founded by Ame Maeght, the uber art dealer (he was the Larry Gagosian or Jay Joplin of his day) and was one of the first private museums. It is situated in St. Paul de Vence, in the south of France and is worth a visit not just for the superb collection of art but also for Sert’s playful and highly sculptural architecture. His form of Corbusian design really works here in the Mediterranean climate and cleverly moderates the baking sun. He had other successes too, when he built Joan Miro’s studio in Mallorca and the Fundacio Joan Miro in Barcelona. Even with these successes, his career and influence cannot be compared to Mies, who is now feted as one of the great 20th century architects. However, he certainly seemed to take a more principled stand against fascism than Mies. But does it matter that Mies worked for the Nazis? Does it diminish his achievements and does it make one think less of his designs?

In a recent interview of Norman Foster by Jonathan Glancy, for a BBC radio program entitled ‘Guilty Buildings’, Norman Foster seemed to imply that architecture must be judged on its own merits and that politics is irrelevant to architecture. He cited the Templehof airport in Berlin, which was reconstructed by the Nazis in the mid-1930s and was once the largest structure in Europe. Its elegant curved plan and use of massive but striking cantilevered trusses protected passengers from adverse weather and accommodated large modern commercial airplanes under its soaring roof, until it was closed down in 2008. In some people’s eyes, the building redeemed itself when it was used during the Berlin airlift of 1948 – 1949. It helped relieve the city of Berlin, when it was in a time of need and when it was being strangled by the surrounding Soviets.

But do buildings have a spirit? Hitler certainly seemed to think so. He placed the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich, designed by P L Troost and built from 1933 to 1937, at the center of the German sense of identity. It was here that he held the ‘Great German Art’ exhibition concurrently in the same building as and in contrast to the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition. David Chipperfield, who has just restored the Royal Academy (and who seems to be flavour of the month in London at present) is currently restoring this impressive building. His plans to remove the screen of trees, that hide the inevitably imposing line of multiple, heavy, sparsely detailed, classical columns, have caused a lot of controversy in Germany. The present entrance is to the side and does not reflect the intentions of the original design. Chipperfield’s plan is to reinstate the original entrance and flow of the building through to the ‘English Garden’ at the rear (now presently a car park and also camouflaged by mature trees). However, he has run into stiff opposition. From his point of view, the trees cannot hide the building because everyone knows it is there anyway and everyone knows the reason for its construction. So why not reinstate the original flow of the building as it was designed and let the architecture of the building speak for itself? It would certainly be better from a circulation point of view, he argues. He also insists that ending a visit with a coffee looking out onto a lush, reinstated green English Garden is correct and makes sense from a user’s point of view.

Proposed view of ‘Haus der Deutschen Kunst’ in Munich as imagined by David Chipperfield Architects with trees removed

However, it seems to me that both Foster and Chipperfield miss a point here. Buildings do symbolise or can come to symbolise a political point of view. Literally, buildings are designed with symbols, which is often the decorative element to them. This has been the case since the frieze of the Parthenon shouted out and celebrated the gods and victories of Athens to its citizens. However, just removing overt symbols of decoration, such as statues of eagles or swastikas, cannot remove the knowledge that certain buildings were designed to be used to send a message that is abhorrent to us now.

For good architecture to be produced a sympathetic client is required with enough resources and the will to build. It is a sad fact that a good client is rare. To produce a good building a good client must be decisive as well as wholeheartedly behind a project, as must the architect. The world of architecture is highly competitive and there are many architects who are willing to compromise to achieve their desires to build. Unfortunately for Mies, his desire to build trumped any thoughts on whether his client’s political agenda was right or wrong.

It might be more palatable to think that architecture stands in a vacuum and is unrelated to the political events and inclinations of the clients who procure the architecture. However, there is always that feeling in the back of one’s mind that, no matter how beautiful and moving the design, materials and space, if the architect was willing to work for an evil client and promote their cause through the use of his or her building, then the quality of the design must be diminished. In any case, Mies’s very contemplative, tranquil and refined spaces seem completely at odds with the program of the National Socialists, so to me it seems especially surprising that he was willing to work for them. By 1935, Hitler had declared himself Fuhrer (in effect, absolute dictator of Germany), the concentration camp at Dechau had been established and the Nuremberg Race laws were passed in September of that year. But are we justified in judging the past by the standards of today? Many would say no, but surely, the knowledge that Mies was prepared to work for the Nazis, must diminish his achievements. He must have known this too, once he became an acknowledged and famous architect. Why else would he have been so determined to wipe clean the unsavoury part of his early design life from the history of architecture?

Image sources:

Barcelona pavilion:

The monument to the November Revolution:

https://rosswolfe.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/mies-van.jpeg?w=700&h=

The German pavilion at the 1935 Brussels Exposition:

The Spanish Republic’s pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair:

https://www.zum.de/Faecher/Materialien/ludwig/wagner/virtual_restoration/english/Htmls/geschi.html

Chipperfield’s ‘Deutschen Kunst’: