Originally published April 2021.

3 July 1938 was a milestone for British engineering. The LNER 4468 Mallard set a new world speed record for steam-powered locomotives between Little Bytham and Essendine in South Lancashire at 203km/hr. More importantly though at the time, it narrowly beat the previous recordholder, Germany’s DRG class 05 locomotive, which had established the previous record at 200.4km/hr only two years earlier.

While the technological rivalry between British and German engineers was replaced by memorable FIFA World Cup matches (“Vergiss 1966!”“Don’t mention 1990!”), rail technology moved on to diesel and electric locomotives. These allowed weight reductions along with less complex engineering as well as aerodynamic designs. Examples include the Fliegender Hamburger high-speed rail service between Hamburg and Berlin reaching a top cruising speed of 160km/hr.

The US saw similar high-speed services at the time, like the ‘Trail Blazer’ between NYC and Chicago reaching top speeds of more than 160km/hr, albeit mostly powered by duplex steam engines. That’s almost a quarter faster than today’s Amtrak trains.

Roughly 20 years later the modern age of high-speed rail travel arrived with the first line of Japan’s Shinkansen bullet trains in the early 1960s, connecting Tokyo and Osaka at a speed of 250km/hr.

Today there are more than 50 purpose-built high-speed lines in operation globally with maximum speeds ranging from 250km/hr to 350km/hr. Compared with regular train service and short-haul air travel, HSR travel provides the following benefits:

- Significantly reduced travel time along with enhanced service quality.

- High frequency (throughput) of train services, enhancing capacity, flexibility and attractiveness compared with other means of transport (car, air travel).

- Efficient direct connection of city pairs or travel corridors with multiple large urban centres, 150-300km apart, achieving agglomeration effects.

- Time efficiency compared with short-haul air services up to 750-1,000km or 3hr travel times.

What are the ingredients to make HSR travel a sensible economic and political decision?

- Access to reasonably priced financing sources, allowing for significant multi-year capital outlays.

- High population density in connected city pairs/travel corridors in order to allow for high track utilisation and capacity demand levels, as well as for affordable and competitive ticket pricing.

- Geographically suitable terrain to keep construction costs and timeframes at bay without jeopardising timely commencement of the cash-generating operations .

- At least 20 million passengers a year with sufficient purchasing power to afford HSR travel (key for developing nations).

- Political will and long-term credit support (co-financing, guarantees etc.), especially for cross-border projects,

How much does a HSR network cost?

Apart from its massive scale and construction speed, the Chinese HSR programme discussed in my previous article achieved something usually not seen in railway’s highly project-driven construction environment: economies of scale and standardisation. According to a 2019 World Bank Analysis, this allowed the country to bring down average construction costs for a standard HSR line, including signalling, electrification and facilities, to US$20.6m/km (~€18.4m/km), US$16.9m/km (~€15.09m/km) and US$15.4m/km (€13.75m/km) for 350km/hr 250km/hr and 200km/hr tracks respectively.

According to research papers published by John Preston and others at the University of Southampton, HSR construction costs outside of China tend to be 60%-100% higher.

Given high population density in East and South Asia, what HSR experience do other countries in the region have?

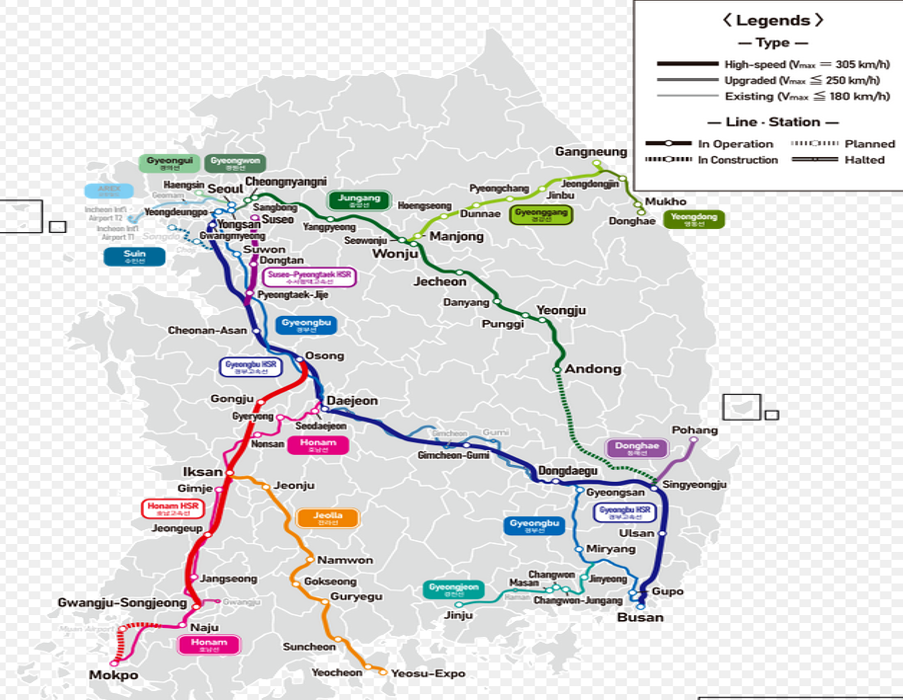

South Korea is a good Asian example. With French assistance, Korea Train Express (KTX) a national network of high-speed services, was built between 1993 and 2004, unifying the country and improving connectivity and economic opportunities. Easing traffic pressure on the country’s most populous corridor, served by the Gyeongbu line between the capital city of Seoul up in the north and the port city of Busan in the south-east, was one of the main objectives.

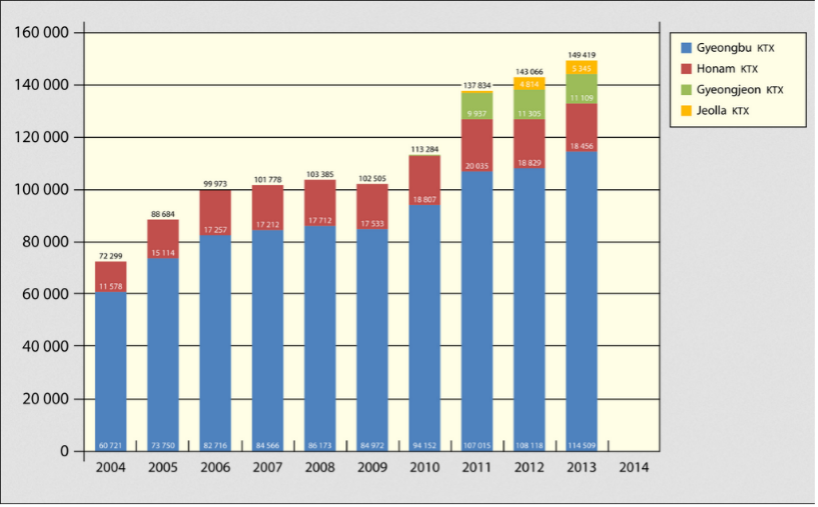

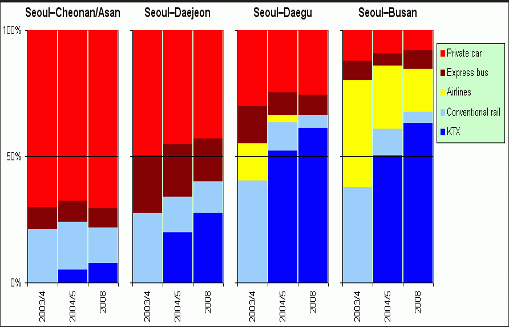

Looking at the uptake in terms of passenger numbers and traffic substitution, the project can be considered a success.

KTX – average daily users

KTX – alternative transport substitution

Vietnam appears to be another suitable candidate for HSR traffic, due to its long and narrow topography as well as its economic trajectory in recent years. A proposed north-south HSR line has been planned across Vietnam for years but has yet to be funded and started in this rather difficult terrain. At top speeds of more than 350km/hr (220mph) the line would link Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, thereby reducing the travel time from currently 32 hours on existing tracks to only seven hours.

India, with numerous densely populated travel corridors, is obviously the other big HSR candidate in Asia. Its first HSR line, with a length of 534km connecting Mumbai and Ahmedabad along the western coast, is currently under construction. Given the sheer scale of the entire HSR network proposed across India, the $1m question will be about timely execution. Given the lessons on achieving economies of scale, this will be the crucial element in order to keep overall HSR construction costs at bay and as such allow for the competitive ticket pricing needed to make the system financially viable to operate.

How about Europe, the cradle of railways?

Europe is at a different stage in its social and economic development, with extensive 100mph (160km/hr) rail networks as well as selected new HS routes at up to 200mph (320km/hr). Compared with China, India or the US as single centralised nations, Europe operated 27 independent national railways with limited powers on the part of the EU to facilitate scale. As we’ve learned on numerous occasions, it’s tough to get 27 railways to work towards one vision and even harder for democracies to implement those quickly.

During the postwar era, Europe did create the Trans Europa Express (TEE) network in the 1950s. This idea is now being revived.

Individual countries such as Spain show some national HSR success stories, with new routes connecting all seven provinces to Madrid in approximately three-hour journeys. The mission was to bring greater economic balance to the Spanish economy. This is now extended into France as part of a new European high-speed network. Italy built a highly successful long-range high-speed route from Turin/Venice to Naples, thus linking Rome, Florence and Bologna and releasing freight capacity on old routes. France’s early HSR example (TGV) linking Paris to all main regions and providing a crossroad for European links (such as Paris–Brussels–Amsterdam) is another interesting reference point as are various upgrades/new lines across Germany.

The next step should be the creation of a trans-European high-speed network super-imposed on domestic networks: for instance, London–Brussels–Frankfurt: Rome–Zurich–Berlin.

Last, but not least, what about HSR in the UK?

Until the 1960s the UK had no history of national rail network construction. This piecemeal approach changed when the existing networks were significantly thinned out in the wake of the Beeching Report recommendations.

Today the UK has a good network of 100-125mph (160-200km/hr) routes – but now capacity is restrained.

HS1 has provided a world class high-speed link to Paris/Brussels which has decimated direct air links and is now being extended to Amsterdam, Frankfurt and possibly night services to Italy. HS1 also provides domestic HSR service from London to Ebbsfleet, Ashford and Kent which has transformed economy, housing and employment. Still, there’s potential to do more.

HS1 has failed to connect to rest of the UK. A missing tunnel under London to HS2 and also to the classic routes to the north (West Coast/East Coast/Midland mainlines) is one of the obstacles.

HS2, the first leg of which is currently being constructed between London and Birmingham, will provide significant economic benefits, level up many regional economies, and release classic line capacity for freight. However, HS2 – which, once completed, will have taken 30 years from conception to delivery – is another example of the headwinds that major infrastructure projects face in Western societies, as already discussed in my recent article on public works in Germany.

HS2 is only one new line and is not part of a planned UK network. It fails to serve 7 million people living south of the Thames (such as Dover to Southampton) or the West of England and Wales. It also does not connect to Europe via HS1.

Rail’s future in the UK will probably lie in shorter high-speed links (such as Liverpool to York) to capture major traffic corridors – and not in a £10bn tunnel linking Northern Ireland (population 1.8 million) with Scotland (population 5 million). As the country’s balance sheet unfolds in a post-Brexit, post-covid world, sensible decisions will have to be made.

Across the world, high-speed rail service has literally come a long way since its modern beginnings in the 1960s. Despite numerous obstacles, I believe HSR will gain momentum going forward, especially if China manages to build a cost-effective HSR export industry around its domestic success and if technologies like the maglev train or hyperloop solutions bring further speed enhancements.

Today there are numerous examples of successful HSR implementations leading to more efficient and environmentally sound traffic flows. Another, no less important lesson, though, is the realisation that railways allow efficient access to a country’s regions beyond large metropolitan areas, helping to create an economic level playing field. In increasingly fragmented societies around the world, this aspect outweighs almost everything else.

Note: I would like to extend my gratitude to the various senior international rail experts who provided valuable input and guidance for this article.