Whatever the popular story of the time, the reason that cycles come to an end is that central banks raise interest rates to suppress inflation.

Initially, business and consumer confidence prevents interest rates from having an immediate effect. Later, leverage and over-expansion on two or three sectors of the economy usually cause a bigger decline in economic activity than is expected. At least it has been this way since the late 1970s.

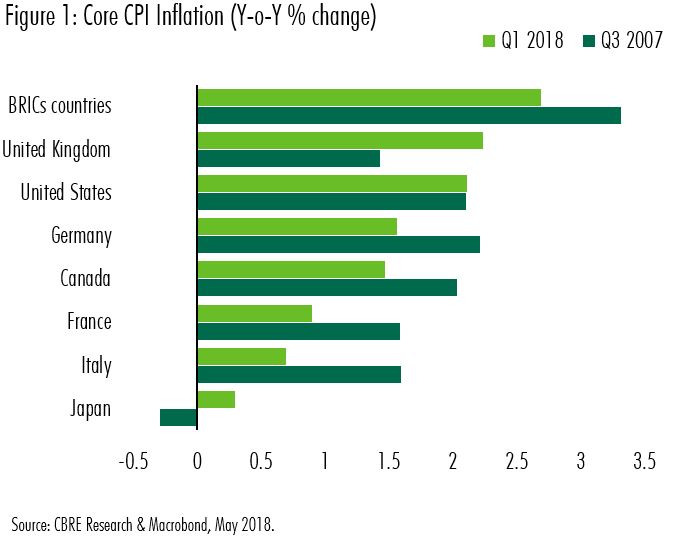

Figure 1 shows the rate of inflation (core CPI) for the G7 and BRICs economies in the year ending Q1 2018, and for comparison, in the year ending Q3 2007, the peak of the last cycle.

- Core inflation (excl. energy and food) is below target in five of the G7 economies and on target in the U.K. and the U.S. It is also considerably lower than at the peak of the last cycle in the most important developing economies (the BRICs);

- The U.K. has the highest core inflation among the G7, which partly reflects a tight labor market but is mainly due to the specific effects of Brexit;

- Abenomics appears to be succeeding in Japan, where the economy seems at last to be breaking out of its long period of deflation. This is one country in which a significant increase in inflation is a good thing!

Why, after almost ten years of economic expansion, is inflation so low?

- The world economy still has spare capacity. Although the U.S., Germany and Japan are operating at full capacity, the rest of the advanced economies still have some slack to use up. The level of unemployment in the EU as whole, for instance, is higher than the previous cyclical low. Emerging markets also have quite a lot of spare capacity, partially due to the severe commodity slowdown that took place between 2015 and 2017. Meanwhile, global capacity may have been increased by the rise of the “sharing economy.” CBRE Research has discussed its real estate and retail implications but the overall economic impacts have yet to be fully understood.

- A sense of insecurity has taken hold of workers in the advanced economies which reduces the incentive to forcefully pursue wage increases. According to The Pew Research Center: “A majority of Americans (63%) believe jobs are less secure now than they were 20 to 30 years ago, and about half (51%) anticipate jobs will become less secure in the future.”

Despite its many benefits, automation, this cycle’s major storyline, undermines economic optimism. “Disruptions” by technological advancements generate many more negative than positive headlines. USA Today’s take on a recent McKinsey report says: “Automation could kill 73 million American jobs by 2030.”

Are we missing anything?

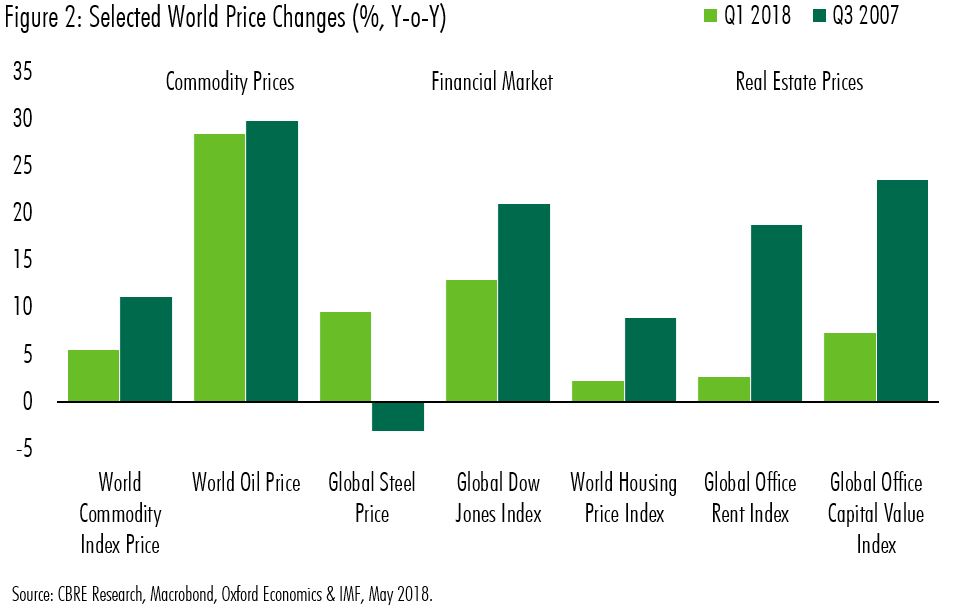

By focusing on the conventional measure of inflation, such as core-CPI, it is possible that we are missing potentially destabilizing price growth in other areas. Figure 2 compares annual price changes of key assets and commodities in Q1 2018 and the end of the last cycle. In general, price pressure looks less intense than before, but there are three possible areas of concern: equities, steel and oil, with the last being the biggest worry. In the tight labor markets of Japan, the U.K., Canada and in particular, the U.S., rising gas prices could trigger stronger pressure for higher wages, but it is not happening yet. Fear of change and gently rising interest rates continue to suppress inflation.

Globally, inflation growth remains muted and spare capacity means that it will likely trend up only very softly in the year ahead. The U.S. may be an exception, with a slightly faster increase in core prices due to labor shortages and rising gas prices. Three further rate hikes in 2018 should be sufficient to get on top of inflation, to be followed by further tightening in 2019.

For the time being, inflation is unlikely to derail the global economy, in part because so many people remain fearful of the future. Oddly enough, that has helped to stabilize growth.