This article was originally published in March 2019.

Over almost 30 years UK house price gains have outperformed the best of British businesses. What next?

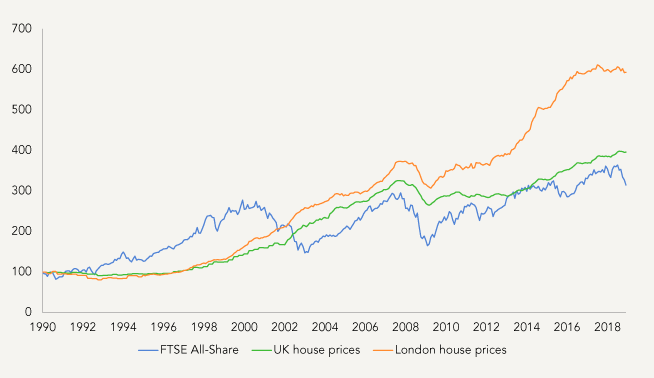

Index performance rebased to 100 in January 1990 %

What’s your biggest financial asset? For most Britons, it’s their home.

2.5 million Britons have doubled down on property and become buy-to-let landlords. Property is a national pastime, as 900 episodes of Homes Under the Hammer testify.

In recent decades – it’s been a great investment. In fact, UK residential property has outperformed UK equities since 1990.

House prices have risen about 4% per annum for 30 years and investors received another 5% or so in rental yield/implied rent. 9-10% total return is very nice indeed. In London the returns have been far greater. But will the future resemble the past?

The advantages of investing in property are well known: it’s easy to understand, tangible and, as a real asset, it has an element of inflation protection. Investors can add value themselves in a way they cannot with a public equity. Lastly, but most significantly, there is access to debt – a mortgage for an 80% loan to value will have magnified investment returns dramatically. Now, try to ask a bank for an 80% loan on a discretionary investment portfolio.

But what if the current environment is as good as it gets for property investors? We are ten years into an economic cycle. Unemployment is at a 47 year low. Rental growth is strong. Mortgage availability is government supported. Interest rates remain nailed to the floor.

Property is increasingly likely to fall

victim to punitive taxation

Often, property just goes sideways. Just ask Victorian homeowners in Boston, USA, who didn’t see prices rise at all between 1860 and 1910!

From an investment perspective there is nothing special about property. Assets are valued based on the present value of future cash flows, or its shorthand cousin – yield. Cash flows are more valuable if they are closer or if interest rates are lower. As interest rates have fallen from their 1990 peak of 15%, the value of cash flow producing assets – bonds, property and stocks – has soared†. Property is simply a long duration asset, one which naturally has benefitted from decades of declining interest rates. It could be vulnerable should they rise.

A generation of rising prices, and indoctrination via TV shows, has convinced the public property is fail-safe. But there are disadvantages.

Property comes with high and rising transaction costs (stamp duty, legal fees, estate agency etc), it can be illiquid and a lack of homogeneity makes comparing prices difficult. The private landlord is cast as robber baron in the play of Populism and is a target for public outrage at wealth and generational inequality. Property is increasingly likely to fall victim to punitive taxation. Problematic, too, is insufficient diversification: buy to let properties are often near the owner’s primary residence and due to high prices investors often end up with just one or two properties. Would we deem a single stock portfolio safe?

Happiness can be found in having expectations exceeded by positive surprises. Property investors need to consider the possibility of an extended period without capital gains as we move into a less favourable economic and political environment.

Perhaps houses should not be viewed as pensions or investments, but as homes. We should heed the standard disclaimer, past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Article originally published by Ruffer.