Income-hungry investors beware: coronavirus fallout makes High Yield even higher risk

Value investing is dead! Warren Buffet knows nothing! Long live drawing random Scrabble tiles out of a bag to pick stocks!

So says day-trading Twitter star Dave Portnoy and his army of fellow sports fans-turned stock speculators. Portnoy’s logic? Stocks always go up, courtesy of Federal Reserve stimulus.

Entertainment factor aside, those Scrabble letters are emblematic of our era – where extreme central bank stimulus encourages speculation over investment and the divorce of financial markets from the real economy.

This is particularly tricky for income-seekers. All that reality-suspending stimulus has seen interest rates and yields plumb ever-deeper depths since the credit crunch. The ‘corona-crisis’ has merely turbocharged these trends, heaping dividend suspensions on income-hungry investors’ misery.

Victorian sage Walter Bagehot once quipped that “John Bull [the personification of England] can stand many things, but he cannot stand 2%”. Today, 10 year UK government bonds yield barely a tenth of that – just 0.2%.1

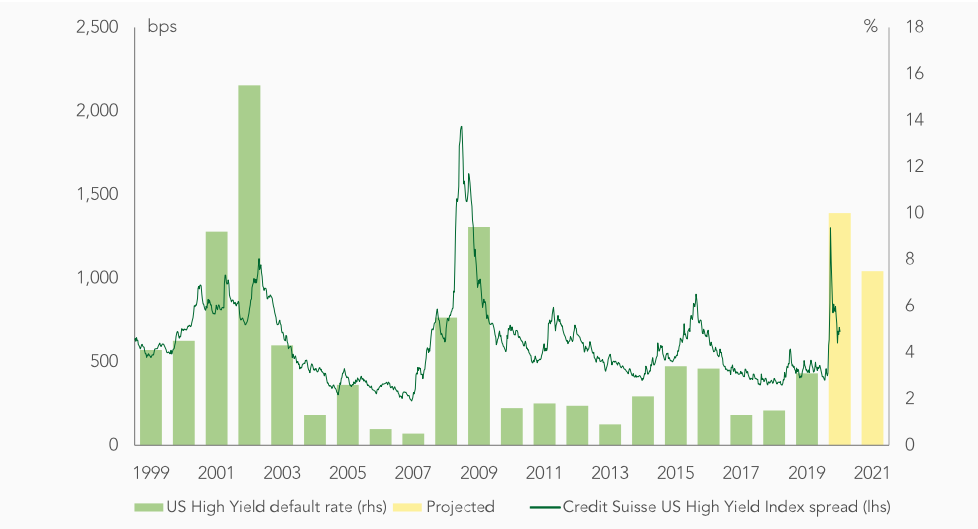

Enter High Yield corporate credit. Sporting yields of 4-5% over government bonds – aka the ‘spread’ (the line on the chart above), John Bull’s heirs have been hoovering up this fundamentally illiquid asset class.

Yet High Yield is also known as ‘junk’ for a reason: default risk is much higher than for ‘investment grade’, especially during a recession as the bars on the chart show.

Coronavirus shutdowns have triggered the worst recession since the Great Depression. Like a depth charge dropped against a submarine, we’ve felt the shockwave but have yet to see how much debris floats to the surface. Ratings agencies suggest the damage is serious and that default rates will soar (the yellow bars above).

And yet, after an initial surge, yields – investors’ compensation for this considerable risk – are practically back to pre-crisis levels. Why? You guessed it – Fed stimulus.

Distressed debt specialists who focus on fundamentals will always find opportunities but, given the risks, generic High Yield looks distinctly low yield. After all, central bank liquidity can support prices, but it cannot fix solvency – the ability of businesses to pay their bills and debts longer-term. If the fallout in the real economy is anything like that of 2008, High Yield investors face losses.

Worse, weaker covenants (creditor protections) – another consequence of a decade of ultra-easy money – mean recovery rates (what investors get back after a default) are falling, too. As Portnoy’s bete noire Warren Buffet once quipped: “it’s not until the tide goes out that you see who’s been swimming naked”.

Finally, the same ‘helicopter money’ which has helped credit markets recover since March is – we think – likely to drive us into a more inflationary era. In it, you will need to think harder about your inflation-adjusted real return, not just headline yields. The Fed giveth, and the Fed taketh away.

So what could investors consider doing?

Adopt a total return approach to drawings – take some capital to supplement income rather than chase high-risk yield. If it looks too good to be true, it probably is. Protect your real returns with inflation-linked bonds. And own punchy specialist credit protections – decided by fundamentals and not Scrabble squares – for when higher risks catch-up with High Yield. We believe in all three.