Things are creaking along, and probably some more lumps to come, but it’s not all that bad

- Deep seek prelude (of Jevons and spend data)

- Multifamily operators getting a bit nervous

- All hail the mods

- “underwater” loans are coming due (but it really doesn’t seem that bad)

- rents are coming down, as non-shortage supply satiates non-infinite demand

- construction workers needed (and other silver linings)

A Deep Seek prelude

You may have heard that a Chinese hedge fund released a powerful foundational model for a fraction of the cost (supposedly).

It seems all to soon to draw any big conclusions yet, but that hasn’t stopped investors from selling off AI-related hardware, en masse. That includes, e.g. Nvidia, but also some of the would-be industrial beneficiaries of increasingly energy-consumptive compute, like the data center liquid cooler, Vertiv VRT -0.76%↓.

Womp, womp.

The “theory” behind the sell-off is basically “if models can be trained cheaply, then who’s going to buy all that expensive compute—and where is all that extra energy consumption going to come from?” SELL, SELL, SELL!

It makes sense so far as it goes, but as I said, seems way too early to make any high conviction conclusions, one way or another (imo), but better to read someone who knows more about what they’re talking about.

A cynic might say he’s talking his book, but Jevons paradox is an apt reference.

It goes like this: the cheaper something gets, the more people use it (which “paradoxically” inures to the benefit of the something-maker).

The point being that, lower cost AI should increase demand for AI, and if AI demand increases more than costs decline, well, the picks n’ shovels will be just fine.

The reason that that is interesting (other than just being interesting), is that there is already some data that demonstrates that “costs go down, consumption goes up.”

Via the expense management company, Ramp:

Token purchases increased, as the average price per token declined.

Now, two lines representing ~2 months of spending data (that in any event, have a pretty funky relationship) does not a trend make.

But, I still like it. Now, on to the show.

Seven real estate charts that actually aren’t so bad

While the rest of the economy seems to have shrugged off higher interest rates, that’s not true of some of the more rate-sensitive sectors, like real estate.

Even so, while there’s definitely been some bending, and even a little breaking, for the most part, it’s been not-so-bad. Sure, new activity is somewhat depressed, and it’s hard to get financing (and investors have definitely lost some money), but for the bets already made, real estate operators and investors appear to be hanging in there.

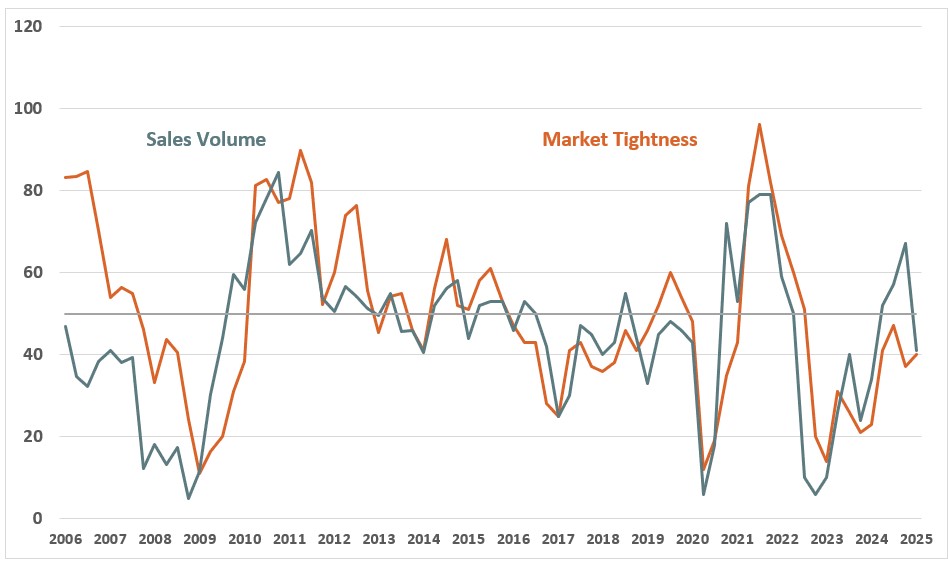

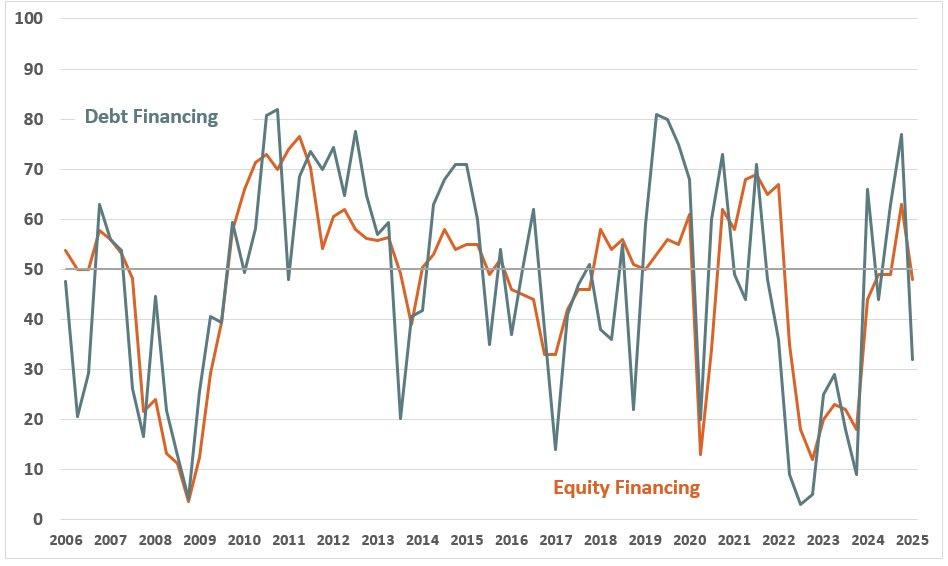

Hanging in there is not sitting pretty, that’s true. And, according to the NMHC quarterly survey of apartment conditions, multifamily operators for their part, are getting a bit *anxious.*

Every survey category dropped below 50, i.e. respondents indicated it was “getting worse:

- market tightness (40)

- sales volume (41)

- equity financing (48)

- debt financing (32)

So, the mood is a bit dour, and perhaps getting worse, but that’s not the end of the world. And that’s just multifamily, which isn’t as bad as office, but is still probably worse than some of the other asset classes, like industrial or retail.1

But, anxiousness aside, as best as I can tell, everyone is continuing to hang in there, even if they’re taking some lumps.

Consider the charts . . .

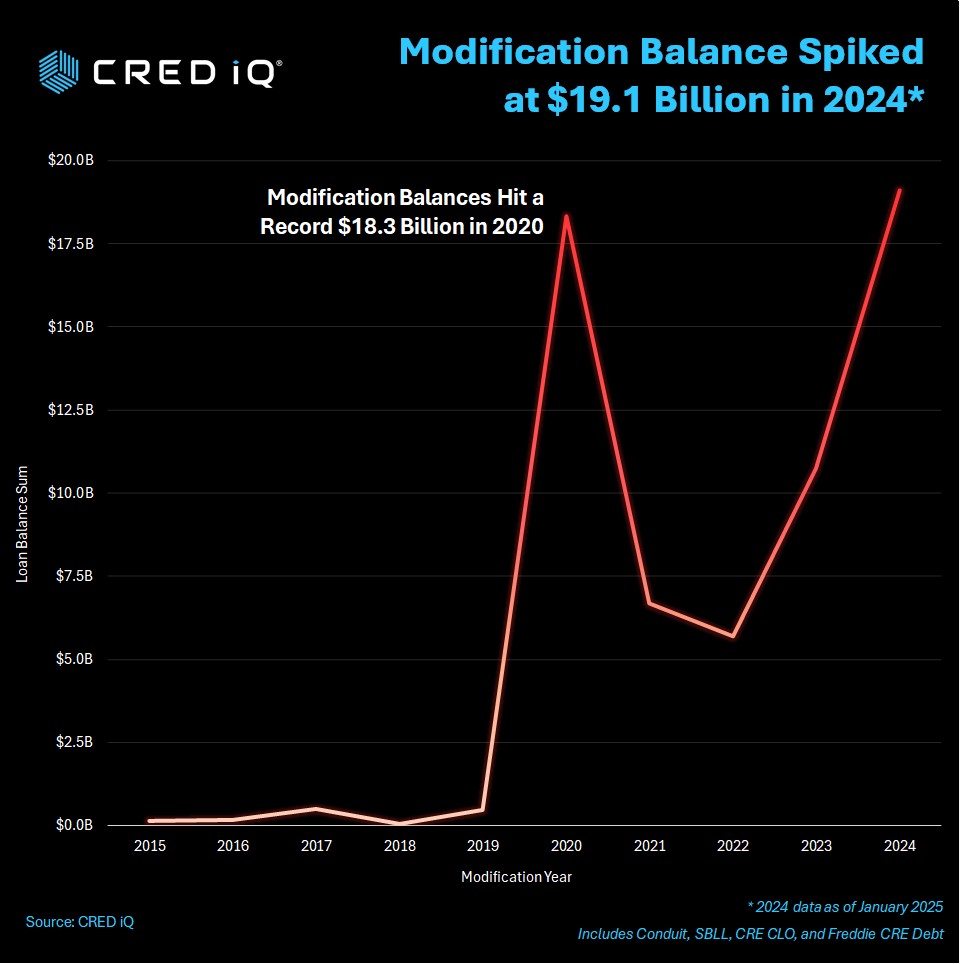

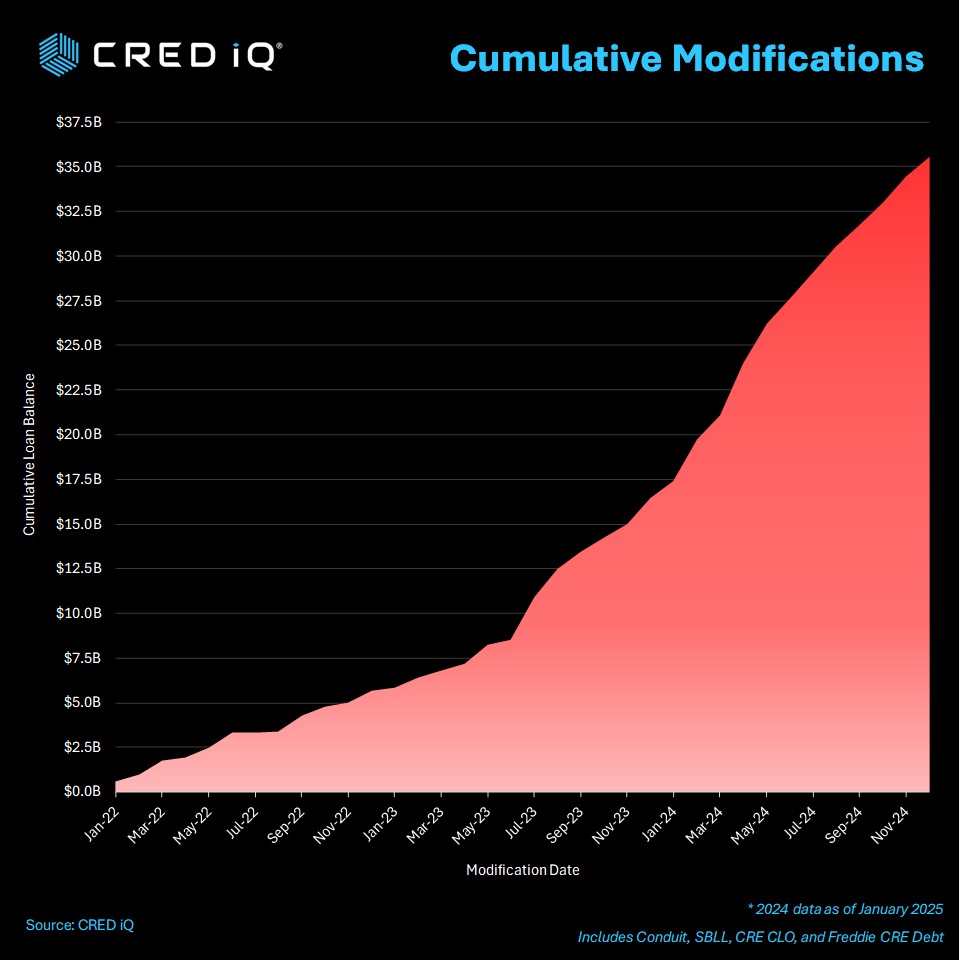

Extend & Pretend, onwards and upwards

Lenders and borrowers have had to get creative to deal with rising rates—deals that made sense when borrowing costs were 3-4% do not make sense when they’re 6-8%.

Rather than simply putting borrowers into default, lenders and borrowers are working it out.

A lot.

Cumulative modifications for CRE loans since rates began to rise has eclipsed $35B.

That’s a lot of modifications, and it’s clearly evidence that at least some of these assets do not support “higher for longer” pricing.

But, we already knew that, and $35B isn’t really that much in the bigger scheme of things. This too shall pass. See? Not so bad.

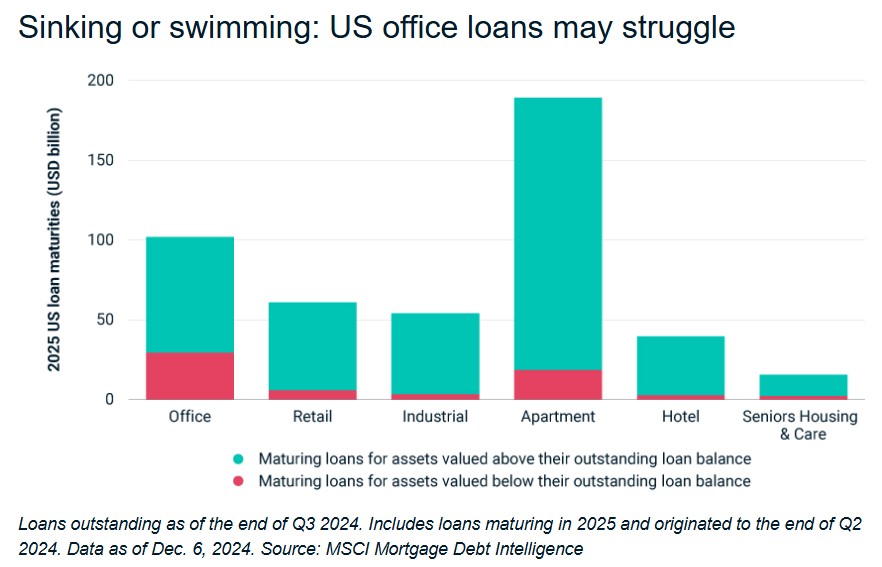

Under-water

Will it get worse, though?

Probably, but nothing suggests that it will get mission-critical worse.

MSCI took a small stab at determining how much worse it will continue to get, and again, while it’s not great, it’s not devastation, either.

MSCI estimates that $500B in loans are set to mature in 2025, and ~14% of those are likely to be underwater, at now-prevailing asset values.

Unsurprisingly, underwater assets are most prevalent in Office:

That’s ~$30B in office assets (and ~$19B in multifamily) that are expected to be worth less than the debt secured by those properties.

So, something like ~$65B in underwater real estate loans coming due in 2025. Nearly 70% of the underwater loans have a 2022 vintage, which is again, not at all surprising.

Even assuming ~50% recovery rates (and that’s pretty conservative), that’s ~$30B in losses . . . which is bad, but given that there’s a little under $5 trillion in outstanding commercial mortgages, $35B shouldn’t bring the house down.

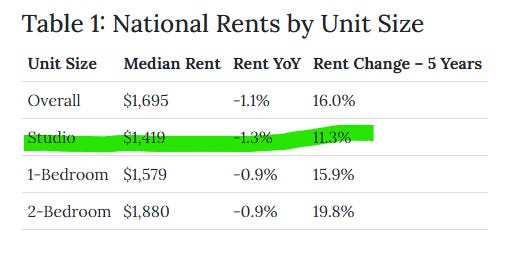

Rents are down (but not out)

Well, higher borrowing costs aren’t so bad, if you can just raise rents, right?

Too bad median asking rents for apartments continue to fall:

Median rents declined 1.1% yoy.

Rent-growth is negative for all apartment types

Studios saw the biggest declines (off the smallest 5-year base, too).

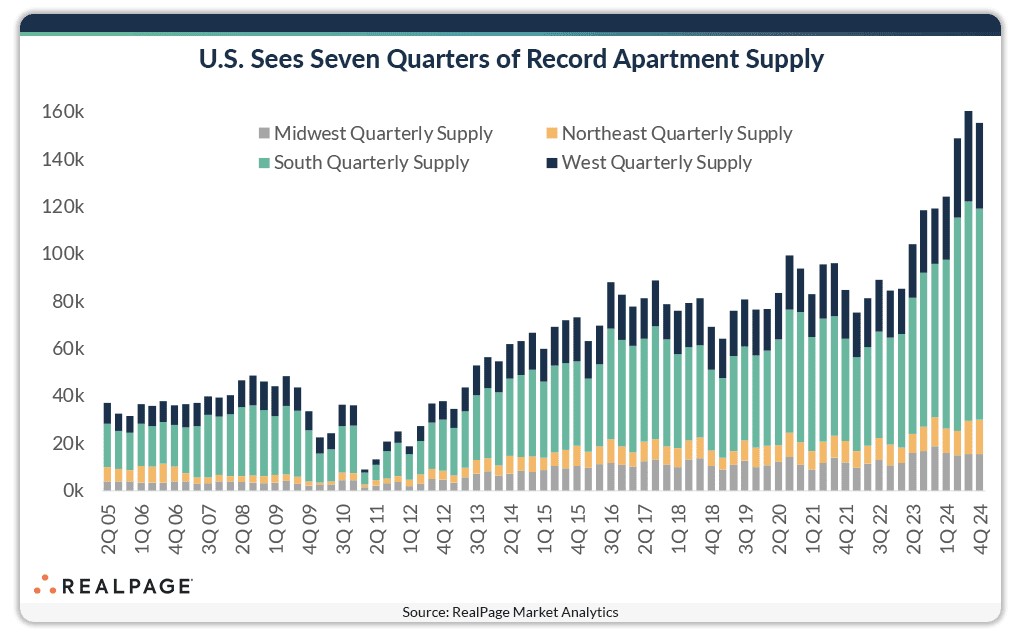

The reason that rents are declining is, of course, because whatever “housing shortage” we supposedly have, it’s gotten a lot better over the last few years, with record levels of supply hitting the market.2

Completed apartment deliveries have skyrocketed because of all the YIMBYism the cheap financing that helped underwrite these projects:

That’s seven quarters of record new apartment supply.

Naturally, with higher costs of capital (and labor), combined with declining rents, developers have already dialed back on new supply (notwithstanding the infinity-demand that housing shortagers would predict).

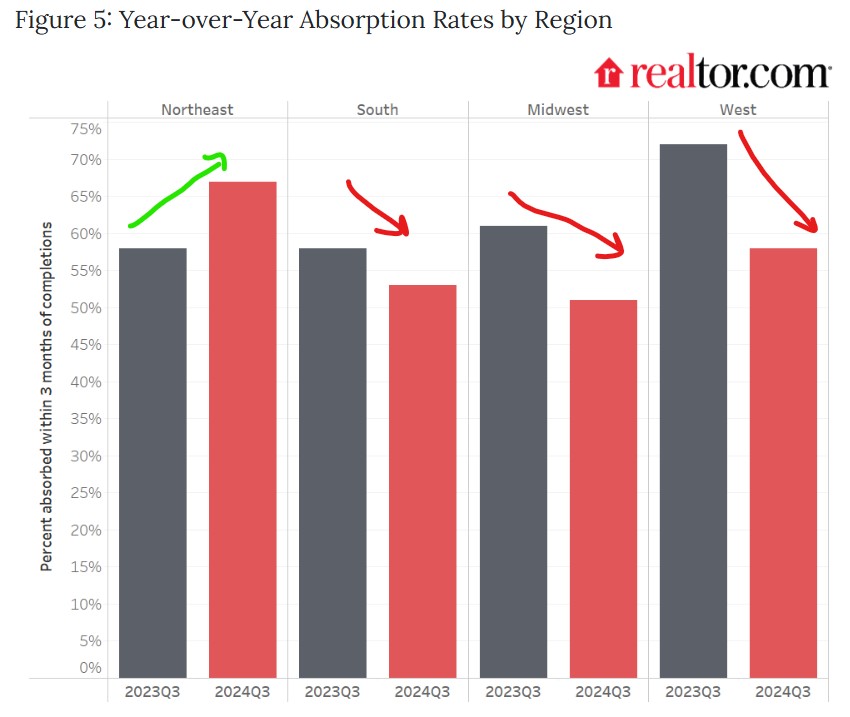

Indeed, absorption rates for new apartments are declining everywhere, with the exception of the Northeast.

The Western region led the way, with a 14bp yoy drop in absorption.

Absorption is the rate at which supply is “absorbed” by demand, and when it goes down, it’s generally a signal of softening demand.

And it’s not just Sunbelt markets, either.

8 out of 11 Western markets reported year-over-year rent declines, led by markets such as Denver, CO (-5.9%); Riverside, CA (-4,8%); and San Francisco, CA (-4.3%).

The absorption rate for new completions also decreased in the Midwest . . . Notably, Cleveland, OH (-3.4%); Chicago, IL (-2.8%); and Milwaukee, WI (-1.2%) were the Midwest markets experiencing the greatest year-over-year rent declines.

Denver, SF, and some midwestern darlings, like Cleveland, experiencing substantial declines in absorption rates, as well.

Again, this isn’t a disaster or anything like that. I mean, it certainly won’t help that 2022 vintage of refis, but it’s no disaster—it is, however, evidence of a well-supplied market for shelter.

Construction workers needed

This one is a bit of a non-sequitur, but I liked the chart, and it touches on some Random Walkian themes (i.e. secular aging, and the inflationary labor shortage that follows).

Plus, rather incredibly, there is a trade organization called the the “ABC,” which stands for Associated Builders and Contractors, and I find that amusing.

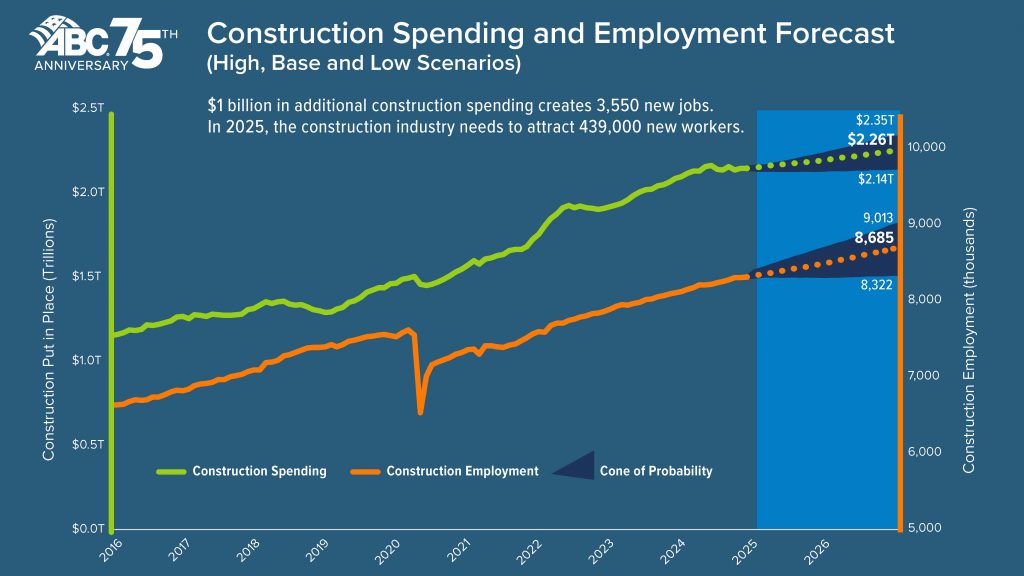

Anyways, ABC says we’re going to need another 439,000 construction workers in 2025:

Even modest growth in construction spending, should beget jobs for another 439,000 men-at-work.

“If it fails to [recruit another 439,000 workers], industrywide labor cost escalation will accelerate, exacerbating already high construction costs and reducing the volume of work that is financially feasible. Average hourly earnings throughout the industry are up 4.4% over the past 12 months, significantly outpacing earnings growth across all industries.”

Makes sense.

Whatever. More jobs good. We’ll see how it goes, if/when deportations really start.

But this is the part that caught my eye:

the industrywide workforce has become significantly younger over the past several quarters, with the median construction worker now younger than 42 for the first time since 2011. As a result, the pace of retirements is expected to slow this year. . . .

“The U.S. construction industry’s efforts to hire more workers to replace retirees and meet the demand for new construction projects gained momentum in 2024,” said Michael Bellaman, ABC president and CEO. “That is fantastic news, but we still have a long way to go to shore up the talent pipeline.

Construction workers are getting younger.

That’s neat.

This article was originally published in Random Walk and is republished here with permission.